Nebraska doesn't elbow its way into travel brochures. It's not built for flash. But dismissing it would be a mistake. The land holds its ground - quietly, steadily - and asks you to meet it on its terms.

What Nebraska offers is space. There's plenty of physical space but mental room, too.

The sky stretches without interruption. Roads that carry the memory of wagon wheels. Rivers that still follow routes older than state lines.

The Platte doesn't announce itself, but its history has shaped it for centuries. Chimney Rock doesn't need a sign to draw your eyes.

And each spring, more than half a million sandhill cranes fill the skies along the Central Flyway. That kind of signal doesn't need volume.

The cues here are subtle and have been in place for generations. If you're sorting out things to do in Nebraska, don't look for neon.

Look for tracks. Look for wind in the grass. Look for the way a place holds onto what mattered - then and now.

Top Tourist Attractions in Nebraska

Nebraska doesn't line things up for display. What it offers tends to sit in plain sight, waiting.

The state leans into its space, letting the land do the talking, letting the past hold steady, and letting visitors find their own pace.

In the east, Omaha and Lincoln carry the largest share of motion. Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo is a year-round draw, with a desert dome and indoor jungle that stretches far past typical exhibits.

In Lincoln, the State Capitol, completed in 1932, stands with clean vertical lines that don't mimic any other U.S. building. Both cities mix sports, college energy, and public art without crowding the corners.

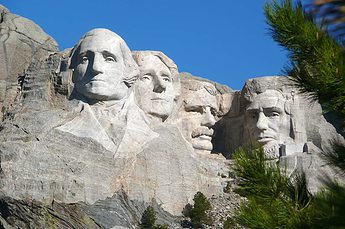

Further west, the landscape opens. Chimney Rock rises from the ground like punctuation.

Nearby, Scotts Bluff served as a landmark for emigrants on the Oregon Trail - its traces are still visible near Mitchell Pass.

North of there, Fort Robinson holds 22,000 acres of Pine Ridge scenery and history that spans Lakota resistance and 20th-century military use.

Sandhill crane migration each spring turns the Platte River basin into a wildlife corridor.

From late February to early April, roughly 600,000 cranes stop to rest and feed between Grand Island and Kearney. The spectacle is timed, regular, and tied to the river's cycles.

Carhenge near Alliance doesn't fit the mold, but it doesn't need to. Built in 1987 from vintage cars set upright and spray-painted gray, it mirrors Stonehenge without explanation.

Visitors still stop. They walk the gravel, take pictures, and then keep driving.

Nebraska's draw isn't concentrated. It spreads - from city galleries to farm roads, from museum halls to bluffs shaped by wind.

If you're looking for things to do in Nebraska, the answer won't come in a countdown. It'll come in pieces - one mile, one trail, one sky-colored afternoon at a time.

10 best places to visit in Nebraska for your next vacation

- Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium

- Lauritzen Gardens/Kenefick Park

- Lincoln Children's Zoo

- Eugene T. Mahoney State Park

- Sunken Gardens

- Carhenge

- Branched Oak State Recreation Area

- Great Platte River Road Archway Monument

- Scotts Bluff National Monument

- Platte River State Park

Nebraska is full of amazing things to see and do. Enjoy a wide variety of attractions and activities across the state.

| Attraction / Activity | Location | Primary Appeal | Best Season | Visitor Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chimney Rock | Near Bayard | Historic trail landmark, natural geology | Spring-Fall | History and trail route travelers |

| Fort Laramie | SE Wyoming (near NE) | Military history, treaties, restored buildings | Spring-Fall | Heritage and military history seekers |

| Carhenge | Alliance | Sculpture made from cars, roadside oddity | Year-round | Road-trippers, curiosity-driven visitors |

| Omaha | Eastern Nebraska | Zoo, arts, restored downtown, riverfront | Year-round | Families, city travelers |

| Lincoln | Southeastern Nebraska | Capitol, university, trails, gardens | Year-round | Culture-focused visitors |

| Lake McConaughy | Near Ogallala | Boating, beach camping, fishing | Late Spring-Early Fall | Outdoor recreation users |

| Niobrara River | North-central Nebraska | Kayaking, tubing, scenic views | Late Spring-Early Fall | Water sport and nature visitors |

| Calamus Reservoir | Near Burwell | Fishing, camping, wildlife spotting | Spring-Fall | Quiet outdoor and fishing visitors |

| Sandhill Crane Migration | Platte River Valley | Wildlife viewing, bird migration event | Late Feb-Early Apr | Birdwatchers, photographers |

| Trail Markers & Ruts | Statewide | Pioneer history, visible wagon paths | Spring-Fall | Water sports and nature visitors |

Chimney Rock

Chimney Rock rises out of the flatlands near Bayard, sudden, narrow, and weathered into shape over time.

It's tall, yes - about 300 feet from the valley floor - but that's not the only reason it held such weight in pioneer journals.

On the wide stretch of prairie that leads up to it, there's nothing else quite like it.

For wagon trains following the Oregon, Mormon, and California Trails, it wasn't just a landmark.

It marked progress.

Diaries from the 1840s to the 1860s mention it again and again.

It meant you were halfway there - or at least far enough to feel like turning back wasn't an option.

The rock stood on the route west, beside the North Platte River, with no towns nearby and no other stone in sight.

That kind of visual break made it hard to forget.

Today, the site stays quiet. The rock itself is fenced off - erosion, wind, and too many footsteps over the years forced that decision.

But you can still get close. A visitor center nearby, built in the 1990s, clearly explains the story.

Photos, maps, and quotes keep the focus on real movement and real places.

Out on the overlook, it still feels like you're watching the edge of something.

Fort Laramie

Technically, Fort Laramie is in Wyoming. But if you trace the old migration routes, it shows up on every Nebraska map from the trail years.

It mattered because of where it was - right where rivers met, where travelers could rest, trade, or find out what was coming next.

Between the 1830s and the 1880s, this place sat at the center of the westward flow. The fort didn't start as a military fort.

It opened in 1834 as a fur trading post, became Army property in 1849, and then grew into a key stop on the trail system.

People fixed wagons here. They swapped out oxen, restocked flour, and picked up mail.

There aren't many other spots on the overland routes that offer all of that in one place.

Buildings remain: barracks, officers' quarters, powder magazines.

Some are restored, some reconstructed, and all of them set against low hills and grassland that stretch out for miles.

Inside the old guardhouse, treaty documents from 1851 and 1868 remind visitors that this was also a place where rules were drawn up - rules that changed where people could live, travel, or stop.

It's quiet now, but that quiet holds weight.

Carhenge

Carhenge is... odd. That's the point. It's a circle of cars planted upright on a rise just outside Alliance.

There's no sign warning you it's coming, no billboards shouting about it.

You just drive a little ways north, and then - there it is.

Perfectly measured. Totally still. And entirely built from old American automobiles.

It was made in 1987. The layout matches England's Stonehenge almost exactly - but instead of stone, it's Detroit steel.

The cars are painted flat gray to match the mood, and the circle holds its shape through careful welding, not mortar.

It doesn't try to explain itself. It doesn't need to. You either stop or you don't. But if you do, you probably stay longer than you meant to.

There's more beyond the circle - metal fish, car-part dinosaurs, even a buried vehicle nose-down in the dirt.

It all sits out under a huge sky, open to wind and weather.

There are no tickets, no fences, and no required route.

You walk the dirt paths, squint at the light off the hoods, and maybe try to line up a photo without anyone else in the frame.

Or you don't. Either way, it's there.

Omaha and Lincoln

If you're looking for movement - concerts, games, food, galleries - you'll find it here.

Omaha and Lincoln carry the pulse of the state, but they move at different speeds.

Omaha spreads wide. Lincoln stacks things a little tighter.

Both cities have grown around walkable centers and green edges that feed into trail systems.

In Omaha, the Henry Doorly Zoo holds attention.

Its indoor desert, rainforest, and ocean exhibits feel less like exhibits and more like shifts in weather.

You walk through one, and you're somewhere else entirely.

Outside, the Old Market district keeps its brick streets and warehouse bones.

It's the kind of place that doesn't have to explain what it used to be.

Lincoln leans on the structure. Government buildings, university quads, public gardens - they're laid out with a deliberate calm.

The Capitol Tower stands above all of it, built between 1922 and 1932. Its murals, mosaics, and high-ceilinged hallways haven't changed much in 90 years.

If you head just a little outside downtown, you'll find lakes, arboretums, and trails that circle back into the city like spokes.

Water Attractions

Nebraska's water is wide but managed. Most of the big lakes, like Lake McConaughy, are reservoirs built for irrigation and flood control.

But they don't feel engineered when you're standing on the shore.

McConaughy's white sand beaches run long and open, with space for boats, campers, and families pulling coolers out of pickup beds.

Then there's the Niobrara River - narrow, winding, and shallow enough in spots to walk across.

Near Valentine, people float it in tubes or paddle canoes past bluffs and waterfalls.

It's steady, easy, and quiet. That makes it good for long afternoons without a schedule.

The river's protected status means it stays that way - undeveloped but open.

Calamus and Branched Oak are smaller.

They pull fewer crowds but offer the same chances for early morning fishing, warm evening walks, or a quiet place to pitch a tent.

A lot of the shorelines are gravel. Most don't have much built around them.

That's part of what makes them work. You don't have to plan much - you just show up.

Sandhill Crane Migration

You hear them before you see them. A low, rolling sound - like something you'd expect from far away, not here.

Then, the sky shifts. Tens of thousands of Sandhill Cranes circle, glide, and drop onto the Platte River's sandbars.

They've done this for generations. Late February through early April, every year, without fanfare.

The river near Kearney becomes the center of it.

At Rowe Sanctuary, you step into a dark blind, wait in near silence, and then, just after the first light hits the water, the birds rise.

It's not choreographed, but it feels that way. They move in waves.

It's slow, then fast. Still, then loud. You don't need binoculars. They're everywhere.

People come from across the country to watch, and most book their spots months ahead.

Local roads are filled with cars pulled to the shoulder, people leaning on hoods, and cameras in hand.

No flash, no drones - just long lenses and windbreakers.

And no one talks much. There's a kind of hush that happens when you're standing near that many wings, that many sounds, all moving at once.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the number one attraction in Nebraska?

The Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium in Omaha draws the most visitors each year. Its desert dome, rainforest, and indoor exhibits cover more than 130 acres. It's been ranked among the highest-attended zoos in the U.S. for over a decade.

What is Nebraska most popular for?

Nebraska is most widely known for agriculture - corn, beef, and soybeans lead the way. The state also draws attention to its role in westward migration trails and the annual sandhill crane migration along the Platte River.

What is the prettiest town in Nebraska?

Many people point to Brownville. It's small - fewer than 200 residents - but it sits right on the Missouri River, with restored 19th-century buildings, bookshops, galleries, and a strong pull for quiet weekend visitors. It holds steady, without flash.

What is Nebraska mainly known for?

Open land, long skies, and early trails. The Oregon, California, and Mormon routes crossed here. You can still see wagon ruts in places. Railroads came through in the 1860s. Farming and ranching shaped the economy, and they still do.

Is there anything fun to do in Nebraska?

Yes - if you like space and time to notice things. You can watch cranes fill the sky at dawn, kayak down the Niobrara River, or drive until all you see is sky and fenceposts. It's the kind of fun that doesn't need music or tickets.

What is Nebraska's most famous food?

Runza is a bread pocket filled with beef, cabbage, and onions - served hot and wrapped tight. It originated from Eastern European cooking and has remained popular. You'll see Runza shops all across the state, especially near Lincoln and Omaha.

What does Nebraska have that other states don't?

It has the Platte River flyway - one of the narrowest, busiest bird migration corridors in the world. Every spring, more than 600,000 sandhill cranes pass through a stretch of central Nebraska, and nowhere else draws that many, that close.

🧭 Nebraska Travel Planning Resources

🏞️ Official Tourism & Outdoor Recreation

- Visit Nebraska - Official Tourism Site

🌾 Explore statewide events, routes, attractions, and regional trip ideas. - Nebraska Game and Parks Commission

🦌 Information on fishing, hiking, camping, and permits across Nebraska's public lands. - Nebraska State Parks

🌲 Guides to state parks, lakes, trails, and nature areas with visitor tips. - Nebraska State Park Reservations

⛺ Book campsites, cabins, RV spots, and shelters across Nebraska parks.

🍀

YOU DONT HAVE FONTENELL FOREST

Sorry, that was the 11th item on the list.