Oregon doesn't require much searching to find places that feel unforced. Condos don't hem in the coast, pay-to-enter driveways don't break up the forests, and the rivers still matter for reasons that have nothing to do with scenery.

The state's layout alone makes it obvious that this is a place built for stepping into, not looking at.

There are things to do in Oregon that don't need translation - walk the beach, watch a launch, follow a river, or ride a chairlift past July. There is no big buildup, no filter, just an activity that fits where it happens.

Overview: The Opportunities, Not the Attractions

The range of things to do in Oregon has less to do with volume than with access.

A 1967 law made every inch of the state's coastline public - no gaps, no locked gates.

Mount Hood offers skiing even in late summer because its elevation and glacier system allow it.

Trail networks lead straight out of towns, not away from them.

And the rivers - the Rogue, the Willamette, the Deschutes - aren't set aside for display.

They're dammed, diverted, or left to run depending on their original purpose: power, irrigation, or transport.

This isn't a state where infrastructure covers the landscape.

Instead, roads often follow their shape, like Oregon Route 138, which tracks waterfalls on the way to Crater Lake, or the Columbia River Highway, finished in 1922 with viewing points built from local stone.

Small towns are still linked directly to their original industries, and those ties show up in what visitors notice: mill stacks, grain elevators, boat ramps, and field-side signs.

What's offered is physical, practical, and tied to a place that still does the work that shaped it.

10 best places to visit in Oregon for your next vacation

- Powell's City of Books

- Oregon Zoo and Washington Park

- Crater Lake National Park

- Mt. Hood National Forest

- Timberline Lodge

- Silver Falls State Park

- Haystack Rock

- The Astoria Column

- Fort Stevens State Park

- Smith Rock State Park

| Activity Type | Example Location(s) | Public Access | Seasonality | Based On |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Hiking | Oswald West State Park | Yes | Year-round | Natural terrain |

| Tidepool Viewing | Cape Perpetua | Yes | Low tide, all year | Natural terrain |

| Skiing | Mount Hood (Palmer Snowfield) | Yes | Year-round | Natural terrain |

| River Rafting | Rogue, Deschutes Rivers | Regulated | Spring-Fall | Natural terrain |

| Sport Climbing | Smith Rock | Yes | Spring-Fall | Natural terrain |

| Scenic Driving | Historic Columbia River Hwy | Yes | Year-round | Built route |

| Small Town Walking | Baker City, Jacksonville | Yes | Year-round | Built heritage |

| Wine Tasting | Willamette Valley | Regulated | Spring-Fall | Agricultural use |

| Fruit Stand Visits | Hood River Fruit Loop | Yes | May-October | Agricultural use |

| Quilt Festival | Sisters | Yes | July | Community event |

| Rodeo Attendance | Pendleton Round-Up | Ticketed | September | Heritage event |

| Crab Season Events | Newport, Garibaldi | Open/festival | Winter-Summer | Marine harvest |

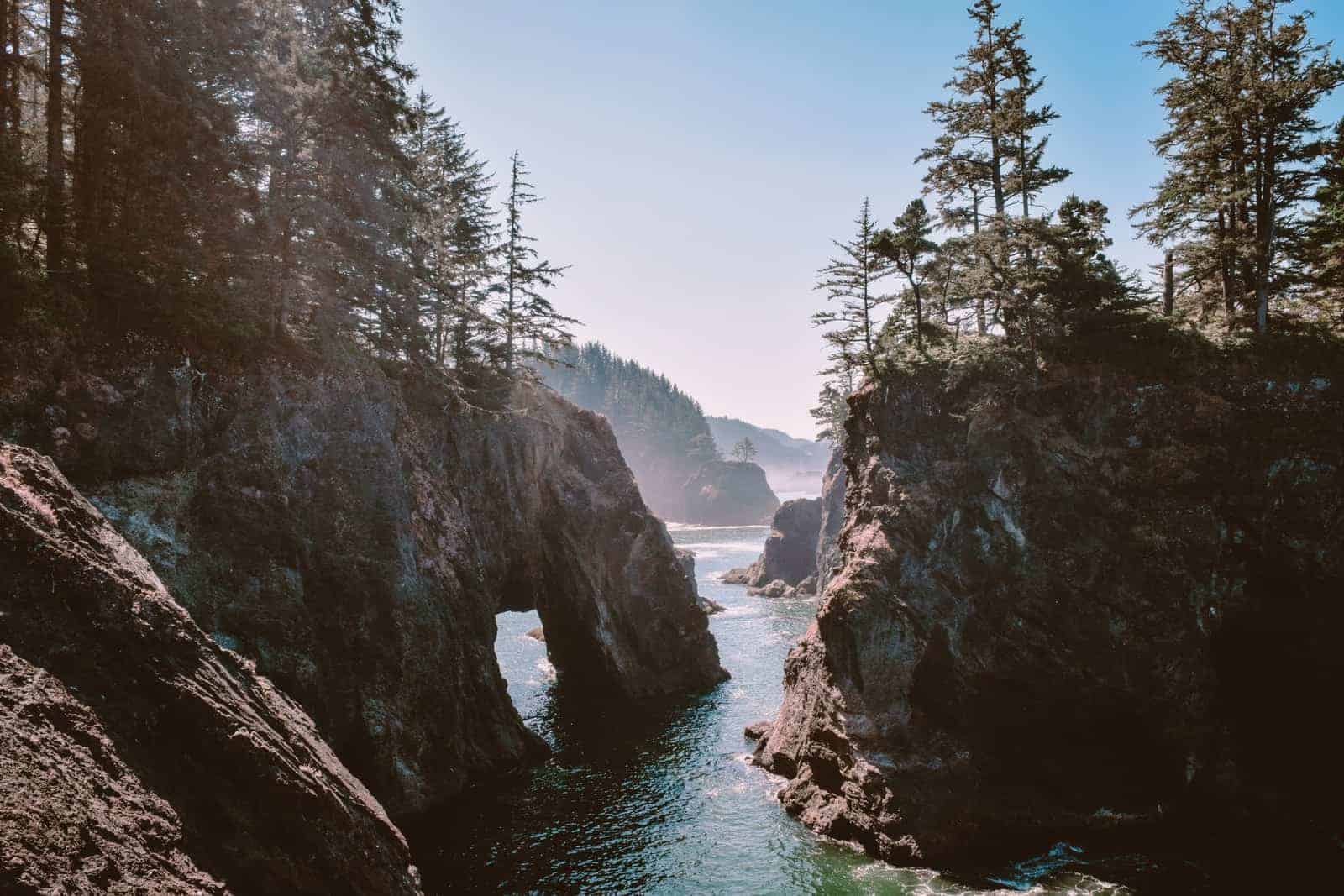

Coastline Access Without Commercial Distractions

Oregon made its stance clear in 1967.

The Beach Bill locked in public rights to the entire stretch of oceanfront - all 363 miles from California to the Columbia River.

That means no private fences, no exclusive resorts, just open coast, from the high tide mark to the edge of the dunes.

The Oregon Parks and Recreation Department manages the access, with the dry sand held in a public easement up to the vegetation line.

Towns like Bandon and Yachats keep a low profile, and that's partly intentional.

Bandon rebuilt after a 1936 fire with brick and stone instead of sprawl.

Beach paths lead past sea stacks carved by erosion, not advertising.

At Cape Perpetua, basalt rock forms tidepools packed with sea stars, urchins, and anemones.

The Forest Service manages this section, and the Civilian Conservation Corps built many of the trails during the Depression.

Oswald West State Park has a forest that runs right down to the shore.

It opened in 1931 and hasn't changed much. Further south, Shore Acres near Coos Bay rises above the water on a cliff edge.

The gardens there once belonged to a timber executive. They were turned over to the state in 1942. Even the lighthouses play it straight.

Yaquina Head and Heceta Head are publicly managed, with walk-in visitor centers and posted hours instead of gift shops.

Mountains Meant for Year-Round Use

Mount Hood keeps its ski season running long after most lifts shut down.

The Palmer Snowfield, sitting above 6,000 feet and fed by a glacier, often stays open through August, sometimes later.

Timberline Lodge anchors the slope, built in 1937 with WPA labor and native materials.

It still functions as a year-round hub - skiers in spring, hikers, and Pacific Crest Trail travelers in summer.

Further down the Cascades, Highway 26 weaves through alpine lakes like Trillium and Frog.

They're open for paddling and picnics in summer, iced over by October.

McKenzie Pass, open only in warm months, climbs to the Dee Wright Observatory, where visitors step out into a sweep of lava.

That structure was finished in 1935 and hasn't changed much since.

Closer to Redmond, Smith Rock pulls in climbers. Its basalt and tuft cliffs played a central role in shaping modern sport climbing.

Routes like Monkey Face and Morning Glory Wall made the early editions of national climbing guides.

Below those walls, trails follow the Crooked River before rising again in sharp switchbacks.

To the southeast, Newberry National Volcanic Monument covers over 50,000 acres.

Inside the caldera, Paulina and East Lakes sit beside fields of lava and black glass.

On clear nights from June through September, the Milky Way is visible without interference.

The light fades, and the crater opens to the sky.

Rivers That Still Shape How Towns Work

The Willamette River runs 187 miles, cutting through cities built along it: Eugene, Albany, Salem, and Portland.

Each one has riverside parks with public docks, trails, and occasional launch ramps.

Most were added between 1970 and 2000, as part of urban cleanup efforts after decades of industrial use.

In Southern Oregon, the Rogue River's whitewater section - from Grants Pass to Gold Beach - draws rafters to stretches marked Class III and above.

Outfitters operate under BLM permits, and the Wild section was federally protected under the 1968 Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

The Columbia River Gorge, carved by Ice Age floods and still eroding today, channels steady wind.

Hood River became a hub for sailboarding in the 1980s - conditions allow 30+ mph gusts on summer afternoons.

On the Washington side, The Dalles Dam, completed in 1957, is one of several along the Columbia where visitors can watch water diverted for hydroelectric use.

At Bonneville Dam, fish ladders are visible through viewing windows during Chinook and steelhead runs, which are most active from April to October.

Upstream, irrigation canals in Hermiston and Boardman draw from the Umatilla and Columbia, feeding large-scale onion and potato farms laid out in pivot circles visible from the air.

Towns That Offer Access Without Reinvention

In Pendleton, the Round-Up grounds are used year-round but come alive every September.

The rodeo began in 1910 and still uses wooden stands and dirt tracks.

Local committees run it, and the arena sits one block from downtown.

Astoria, at the Columbia's mouth, maintains a working port - tugs and barges still move past the 1913 wharf.

A trolley runs on original tracks, restored in 1999 using volunteer labor.

No entry gates, no loop rides - just a flat fee or donation.

Baker City, once a mining and banking hub, still shows off that scale in buildings like the 1889 Geiser Grand Hotel.

The main street holds outfitters and a bookstore in turn-of-the-century blocks.

Klamath Falls, farther south, aligns with old timber transport routes - trains, trucks, and barges.

You can follow the tracks right from Main Street.

Jacksonville sits west of Medford, with brick storefronts dating to the 1850s.

It became a National Historic Landmark in 1966. Businesses operate in the original buildings, with no overlay of themes.

Silverton, east of Salem, started commissioning wall murals in the 1990s.

Local artists paint them directly onto brick and cinderblock, without plaques or maps.

Agriculture With Direct Access to the Public

Oregon grows nearly all of the country's commercial hazelnuts.

The Willamette Valley, especially near Aurora and St. Paul, holds large orchards, visible from Highway 99E.

From May through October, roadside stands sell fruit picked that morning - pears, plums, apples, and blueberries.

The Hood River Fruit Loop, a 35-mile self-guided drive, loops through orchards and farms.

Many have been in the same family since the early 1900s.

It's mapped and updated annually by the Hood River County Chamber of Commerce.

Marion County is known for grass seed; Linn County leads in mint and ryegrass.

Those aren't visitor crops, but they shape the fields: green in spring, tan by August.

Near Newberg and Dayton, lavender fields bloom in June and early July.

Some are open to visitors on weekends, posted by roadside signs, but there are no ticketing platforms or booking windows.

Eastern Oregon, around Burns and Enterprise, still runs ranch-style agriculture.

During branding weekends in May, ranches often open their fences - spectators can watch from the gravel road.

Oregon State University's extension offices print harvest calendars based on county and crop, published each February.

Events Rooted in Geography or Labor

The Oregon Country Fair began in 1969 on land near Veneta.

It spans three days in July and still runs on community-built paths through wooded grounds.

Booths are made of hand-joined wood, not metal poles or vinyl.

The Portland Rose Festival dates back to 1907 and aligns with the bloom cycle in Washington Park's test garden, planted in 1917.

The Grand Floral Parade takes over city streets in early June, closing bridges and rerouting buses.

In Sisters, the Outdoor Quilt Show started in 1975 as a shop display.

Now it takes up the whole town - quilts hang on exterior walls and fences for one Saturday each July.

There are no plastic covers, and there are no indoor exhibits.

Hayward Field in Eugene was rebuilt in 2020 but has hosted U.S. Olympic trials for decades.

The stadium, owned by the University of Oregon, sits on the same ground where Prefontaine ran in the 1970s.

Its track program still holds NCAA meets and international qualifiers.

Pacific City, on the coast, launches fishing dories from the beach - no ramp.

That method dates back to the early 1900s.

State regulations define crab seasons, usually December through August, and local events like Newport's Crab Fest are timed to match legal catch periods.

Scenic Routes Designed to Show, Not Hide

The Historic Columbia River Highway, built from 1913 to 1922, used dry masonry to fit into the cliffs.

Rest stops and overlooks - Crown Point, Latourell Falls - were part of the original plan.

Unlike many scenic byways, this one was engineered with pedestrians and drivers in mind.

McKenzie Pass (Highway 242), open from late June through October, ends at a lava field where the Civilian Conservation Corps built the Dee Wright Observatory in 1935.

It's the only lookout made entirely from the surrounding volcanic rock.

Oregon Route 138 leads from Roseburg to Crater Lake.

Between Glide and Diamond Lake, there are pull-offs for more than a dozen named waterfalls.

Many, like Watson Falls and Toketee Falls, sit within a five-minute walk of the highway.

The Outback Scenic Byway begins in La Pine and runs southeast to Lakeview.

It crosses sagebrush plains with open grazing, often unfenced.

Pronghorn antelopes are seen most often from April through early fall.

Route 101, the coastal road, was finished in 1936.

Viewpoints were built into the cliffs - Cape Foulweather and Cape Lookout - sometimes with low stone walls and pull-throughs.

Oregon Route 395, running north to south, keeps to two lanes across most of the state, connecting towns like John Day and Burns without bypasses or commercial clusters.

FAQ

What is the number one attraction in Oregon?

Crater Lake often takes that spot. It's the deepest lake in the U.S., formed by a collapsed volcano and known for its clear water and steep caldera walls. The rim drive, open seasonally, gives access to nearly all viewpoints without needing a guide.

Is there anything fun to do in Oregon?

Yes - if you like your activities tied to geography. You can hike right to ocean cliffs, ski well into summer, raft rivers used for irrigation, or walk through towns that still look like the year they were built. Oregon doesn't separate activity from place.

What is Oregon best known for?

It's known for land that's still in use, forests that are logged and hiked, rivers that power homes and float boats, and a public coastline that is open to anyone. The state made early decisions, like the 1967 Beach Bill, that shaped what's possible on the ground.

What is the best month to go to Oregon?

July. High-elevation roads like McKenzie Pass are open. Berry stands are full. Coastal mornings are foggy but clear by noon. Mount Hood still has snow above 6,000 feet, and eastern Oregon skies go clear at night with almost no light interference.

What's the prettiest place in Oregon?

That depends on how you see "pretty." Crater Lake has the color. The Columbia Gorge has the scale. But the Alvord Desert in the southeast - flat, dry, and wide open - feels like another planet. At sunrise, it's all shadow and shape.

What is Oregon's famous food?

Dungeness crab is caught off the coast from December through summer. It's sold dockside in Newport, Garibaldi, and Astoria when the season's open. Marionberries - a hybrid developed by Oregon State University - also show up in pies and roadside jams.

What is the coolest city in Oregon?

Astoria sits on the Columbia River, blocks from where it meets the Pacific. It still runs as a port town, with a working waterfront and boardwalk. Without stepping out of town, you can see container ships, salmon trawlers, and grain elevators.

What is the most visited waterfall in Oregon?

Multnomah Falls is east of Portland in the Columbia River Gorge. It's 620 feet tall and visible from the historic highway. The upper trail, built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, still connects to Larch Mountain when snow has cleared.

🧭 Oregon Trip Planning Resources

🗺️ General Travel Planning

- Travel Oregon - Official State Tourism Site

🌲 Comprehensive resource for trip ideas, itineraries, and travel alerts. - Oregon Travel Information Council

🚏 Information on rest areas, scenic byways, and heritage trees across Oregon.

🏕️ Outdoor Recreation & Camping

- Oregon State Parks - Park Information and Reservations

🏞️ Details on campgrounds, day-use areas, and heritage sites with reservation options. - Reserve America - Oregon State Parks Reservations

⛺ Online reservation system for campsites, cabins, and yurts in Oregon State Parks.

🚗 Road Conditions & Transportation

- TripCheck - Oregon Road Conditions and Travel Information

🛣️ Live updates on road conditions, traffic incidents, and weather forecasts. - Oregon DOT - Travel Resources

🚍 Public transportation information and state-wide travel planning tools.

🍷 Wine Country Exploration

- Oregon Wine Board - Wine Country Info

🍇 Explore Oregon's wine regions, tasting rooms, and vineyard events. - Willamette Valley Wine Region

🍷 Discover wineries, tours, and scenic routes through the Willamette Valley.

🏛️ History & Culture

- Oregon Historical Society

🏛️ Exhibits, archives, and events focused on Oregon's past. - Oregon Blue Book - Regional Historical Societies

📜 Listings of local museums and historical societies across the state.

📚 Travel Guides & Itineraries

- Free Oregon Travel Planners and Guides

📘 Download or request travel planners featuring events, routes, and lodging. - Oregon Wine Touring Guide

🗺️ Detailed guide to Oregon's wine trails, maps, and insider travel tips.

🍀