Nothing About It Was Temporary

Evansville had never seen a library like this. Finished in 1885 after years of delay, Willard Library came with rules that didn't shift with the weather - free for everyone, governed by a board, funded through a trust.

Most of the stone was carved. Some wasn't. That part stayed unfinished. So did the ghost stories.

What was built to serve the public kept doing so, even when the rest of the city's buildings turned into stores or offices.

The Ground Stalls, Then Holds

Willard Library started with a trust.

In 1876, Willard Carpenter laid out his intent in writing: to create a public library for Evansville, set in a park on his land at First Avenue and Pennsylvania Streets.

He wrote that it should support the "moral and intellectual culture" of residents, and the design included free access for all, worded plainly, with no conditions.

That clause would matter more over time than he could have guessed.

Construction got underway in 1876 but didn't last long.

A national economic downturn cut short the early progress.

The foundation sat exposed for five years, untouched through rain and snow.

Locals called it "Carpenter's Folly." From 1877 to 1882, the half-finished site was quiet - until Carpenter resumed the work himself.

He hired the laborers, oversaw the materials, and partnered with the architectural firm Reid & Reid to complete the building.

The final push lasted three years. On March 28, 1885, the library opened to the public.

By then, Evansville had grown. The train tracks weren't far off, and circuses that once used Carpenter's field had long since moved on.

What had been an idea tied to an individual was now a physical structure on the city's map.

That same year, the trust was incorporated, formalizing the terms he laid out nine years earlier.

The Building of a Landmark

Sharp gables cut the sky. Arched windows lined the façades in rhythmic patterns.

Terra cotta owls - an emblem of wisdom - perched in roundels along the gables.

The contrast between red brick and pale stone made the building feel taller, colder, and older than anything else around it.

The architecture didn't whisper its purpose. It broadcast it.

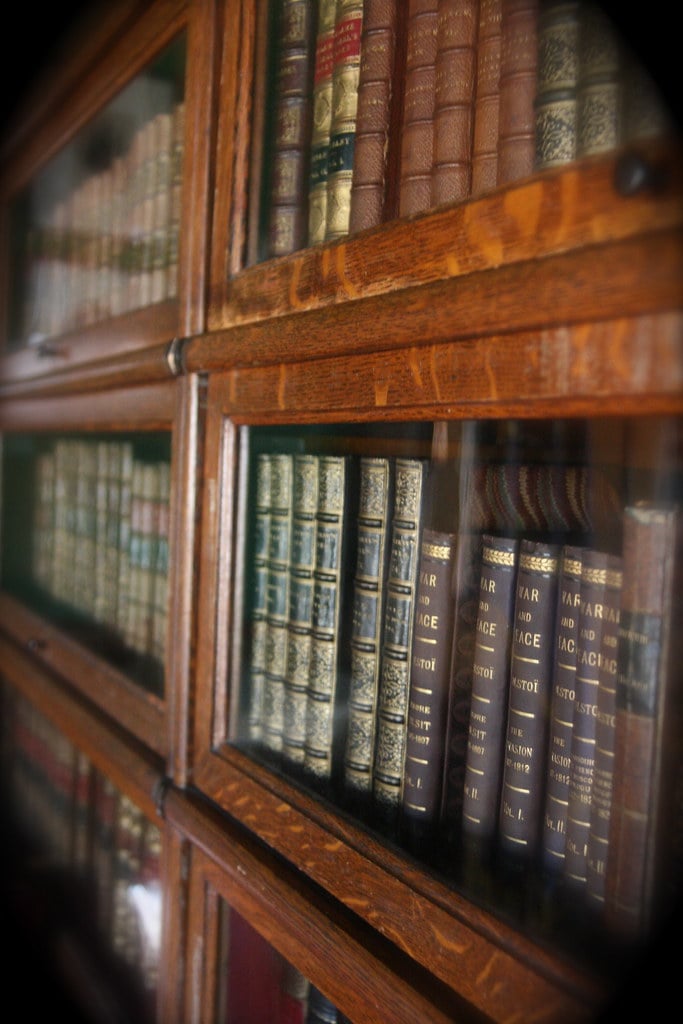

Inside, the mood shifts, but the control doesn't loosen.

Quarter-grain oak lines the rooms. The grand staircase doesn't creak or lean - it commands.

Capitals on the arcade arches were left roughed out, never fully carved.

Whether that was an oversight or a decision isn't recorded. Either way, they hold.

By the time the library opened in March 1885, Evansville had a structure that didn't borrow style from other civic buildings.

It borrowed from chapels and halls across the Atlantic.

In a city shaped by commerce and coal, Willard Library planted a stake for permanence, detail, and quiet ambition.

The Genealogical Treasure Trove

The second floor of Willard Library doesn't make noise, but people spend hours there.

In August 1976, that floor was remade into the library's Special Collections department.

Since then, it's turned into one of the region's deepest wells for genealogy and local research.

The microfilm drawers don't advertise what they hold.

Neither do the stacked family histories in manila folders.

But they get pulled, daily, by people looking for names no longer spoken out loud.

The department's strength lies in its range. Vanderburgh County newspapers going back to 1821.

Church ledgers. Cemetery plot records. Catholic Diocese microfilm.

DAR indexes. Ancestry Library, Heritage Quest, and GenealogyBank search engines are wired into the terminals.

None of it feels flashy. All of it gets used.

What's on offer isn't limited to local files. Researchers dig into out-of-state references, track migrations, and build timelines.

It's not unusual to see someone spend six hours with one reel of film, looking for a single obituary, a single mention, a thread to pull.

The Tri-State Genealogical Society shares space and purpose.

Their quarterly packets go out to members in September, December, March, and June.

The two groups - library staff and society volunteers - keep the machine turning, quietly but with discipline.

If Evansville has a public archive of its personal histories, this is it.

And it doesn't try to impress. It just waits for people to ask the right question.

Library Without a Gate

The structure is private. The access is public. Willard Library has always sat at that crossroads.

Since its incorporation in 1881, it's been governed by a self-perpetuating board of seven members, none elected.

But the doors stay open to anyone in Vanderburgh County or nearby.

Free, no ID required. No gatekeeping, literal or otherwise.

Its funding, though, comes with strings. The library receives support through a public tax levy.

That levy isn't automatic. It must be approved by the Evansville Vanderburgh Public Library system - a separate entity with its structure and oversight.

The result is a hybrid: privately directed, publicly supported.

The library operates in its rhythm. It doesn't run like a retail branch of a larger system.

Events like "Midnight Madness" are shaped around research habits, not seasonal calendars.

The building stays open until midnight for one week a year, attracting researchers who plan their trips around those hours. It's practical, not promotional.

Education has stayed part of the mission, even if it's carried out through archives and queries rather than lectures.

Public school teachers refer students here for local history projects.

Area researchers use the space for background work on books and academic papers.

The staff doesn't offer classes - they offer documents.

Nothing inside has been staged to feel like a modern civic center.

There's no café, no touchscreen directory. Instead, the place leans on paper, film, and maps.

What you find depends on what you ask. And whether you keep looking.

The Business of a Ghost

The Grey Lady isn't listed in any founding charter, but she's become part of the Willard Library's daily operations.

The first sighting came in 1937 - a custodian claimed to see a figure in the basement, then left his job soon after.

There's no formal record of that resignation, but the story has stuck.

Since then, others have described cold drafts, perfume with no source, and light footsteps in empty stairwells.

By the late 1990s, the library stopped brushing it off.

In 1999, six webcams were installed in various corners of the building.

The setup wasn't a tech stunt - it was aimed at people who said they had seen things but had no proof.

The cameras stream day and night. Still images refresh every 30 seconds. People screenshot shadows and reflections. Most go unverified.

Multiple versions of the ghost's origin exist.

One theory holds that she's Louise Carpenter, who sued the library board in the 1890s after the loss of her father.

She lost the case and was cut out of the estate. That story points to revenge.

Another version, more local, says she was a librarian whose child fell from a ladder.

No date has ever been confirmed for that event. Either way, the sightings tend to cluster near the second-floor windows.

Every October, ghost tours run through the building.

They're scheduled, ticketed, and well-attended. Paranormal investigators stop by. So do skeptics.

Meanwhile, the Grey Lady keeps her schedule. People still glance toward the staircase.

Some say they feel watched. Most say nothing.

🍀