Fonthill Castle and the Art of Concrete

In 1908, Henry Chapman Mercer began pouring his own house by hand. Each day, he mixed concrete, testing what shapes the material could hold.

He built with no architect, no formal plan, only clay models and sketches. By 1912, the castle stood finished, gray and permanent above Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

The walls kept the imprint of the wooden molds. Light passed through more than two hundred windows.

Mercer had proven a theory: that a house could resist both fire and conformity.

He had studied law at Harvard but abandoned the field for archaeology and the crafts of an earlier America.

In the age of machines, he built by hand.

Fonthill Castle was to be both his home and his argument.

Every curve, stair, and arch was cast in place. Even the chairs and tables were poured from the same mix.

He called it his "Castle for the New World," a phrase that held equal parts pride and defiance.

The Man Who Built His Own Museum

Henry Chapman Mercer was born in 1856 in Doylestown, the son of a prominent family.

As a child, he collected anything that caught his eye: old tools, handmade objects, pieces of the past.

By his fifties, he had gathered thousands of pre-industrial artifacts.

He built his castle on the land where he'd grown up.

The workers he hired had never handled wet concrete, so he taught them as they went.

They made wooden molds, carried heavy buckets, and pressed designs into the fresh surface.

His horse, Lucy, hauled the mixed concrete from the pit up to the walls.

Mercer built slowly, layer by layer, through every season.

When the structure began to take shape, he tested his idea by lighting small fires inside.

Smoke curled along the ceilings, but the walls stayed unmarked.

Concrete, he decided, could outlast wood, steel, and whatever style came next.

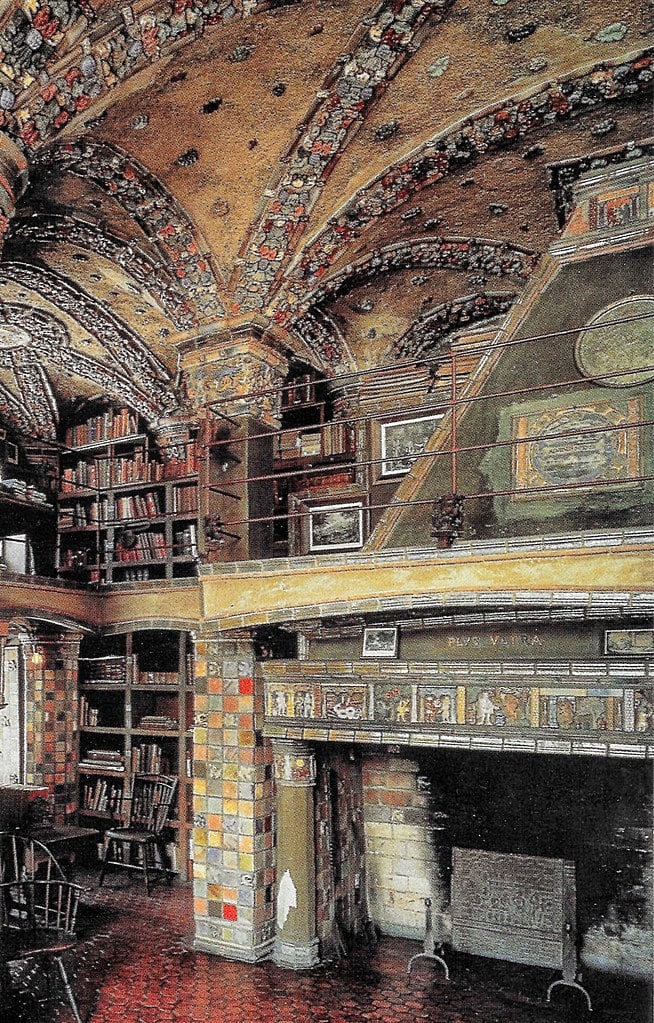

Rooms of Stories and Symbols

Inside, the rooms multiplied like thoughts branching from a single idea.

There were forty-four of them, linked by narrow stairways and low arches.

Latin inscriptions wound along the walls, invoking knowledge and memory.

Tiles lined the surfaces, each one a record. Some came from his own Moravian Pottery and Tile Works next door.

Others had traveled farther: roof tiles from China, cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia, fragments of European ceramics.

Even memento mori skulls were set into the concrete.

Books and prints filled the shelves, over six thousand volumes in all.

The place became both laboratory and gallery.

Mercer lived among his collection, sleeping under ceilings he had cast, writing notes in the margins of nearly every book he owned.

Life After the Maker

Mercer died in 1930, leaving the castle and its contents to the community.

His will directed that it remain a museum of decorative tiles and prints.

He granted life tenancy to his longtime housekeeper, Laura Swain, and her husband, Frank.

Laura stayed for decades, guiding visitors through the maze of rooms.

Her presence kept the house alive while the world outside shifted through depression and war.

After she died in 1975, trustees assumed care of the property and opened it more fully to the public.

In 1990, the Bucks County Historical Society became the permanent steward.

The castle, Moravian Pottery, and the nearby Mercer Museum formed a connected landscape of his vision, preserving the handmade against time's wear.

Fireproof Dreams, Lasting Walls

From the start, Fonthill Castle was an experiment in how far one material could go.

Reinforced concrete shaped its bones and its ornament.

Built-in tables, fireplaces, and stairways show no join between structure and art.

Visitors today still walk on uneven floors cast more than a century ago.

Many rooms retain their soft pastel tints, now faded.

The castle's design borrows from Gothic and Byzantine forms yet belongs fully to neither.

It feels improvised, alive to the moment of its making.

Mercer's innovations placed him ahead of most American builders of his era.

What began as an eccentric's project became a model for resilience and imagination in early twentieth-century design.

Recognition and Renewal

Fonthill Castle entered the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and later became part of the National Historic Landmark District shared with the Mercer Museum and the tile works.

The Bucks County Historical Society has since kept the site active, hosting tours, school programs, and seasonal events like candlelight walks and Shakespeare in the Park.

More than thirty thousand people visit each year.

Some come for the architecture, others for the story of one man working against industrial uniformity.

The castle has been featured in national media and continues to attract study for its experimental construction.

In 2012, the Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia honored it with a Historic Preservation Award.

The American Alliance of Museums and the National Trust's Historic Artists' Homes and Studios program both recognize its standing.

The Legacy Beneath the Concrete

Mercer left himself inside these walls.

His handprints still press through the plaster, and the joins between molds run uneven, like seams in old cloth.

The castle is his handwriting in concrete.

It has lasted because people refused to let it fall.

Each year, the roofs are sealed again, and loose tiles are fixed before winter.

The work is quiet, but steady - just enough to keep the rain out and the story intact.

From the courtyard, Fonthill Castle looks nearly the same as it did in 1912.

The towers don't line up; the windows catch bits of daylight through the trees.

Inside, the rooms hold a stillness that feels earned.

The air is thick with time, and with the labor that never really stopped.