A House That Didn't Flinch

Before bullets tore through the parlor, before cannon fire punched holes in the floorboards, the Lotz House stood clean and sharp on Columbia Pike.

A woodworker built it to show what he could do with walnut, hand tools, and no outside labor.

Six years later, war kicked in the front door. The staircase held. The walls cracked. What started as a shop floor became the middle of the Battle of Franklin.

Building Lotz House from the Ground Up

In 1848, Johann Albert Lotz sailed into New Orleans with a trade and no plan beyond that.

He was already a master in the German guild system, and when he moved to Franklin, Tennessee, he brought his tools and his title.

By 1855, he purchased five acres from Fountain Branch Carter, carved out from Carter's larger 300-acre tract on Columbia Pike.

Local speculation, later repeated by historian J.T. Thompson, held that the land was too rocky to farm.

Carter sold it anyway, and Lotz started to build. He finished the house in 1858.

It stood two stories tall, framed in white wood, with a Greek Revival face that gave it a kind of formal presence along the road.

Lotz didn't just live in it. He used it as a demonstration site for his craft.

Inside were three fireplaces, each designed with a different level of detail, and a black walnut staircase with a continuous handrail that curled upward from the first floor to the second.

He carved it himself.

The house had no outbuildings for enslaved labor. It wasn't a plantation. It was a working man's home with display-quality joinery.

He built pianos, cabinets, and beds. He had six children with his wife Margaretha.

Paul and Amelia came from a previous marriage. Augustus, Matilda, and the twins Julius and Julia were born later.

The house held them all, and in 1864, it held the sound of artillery.

But six years earlier, it was still clean, sharp-edged, and new.

Franklin might show up on lists of things to do in Franklin, TN, now, but in 1858, it was just a market town with a craftsman's house on Columbia Pike.

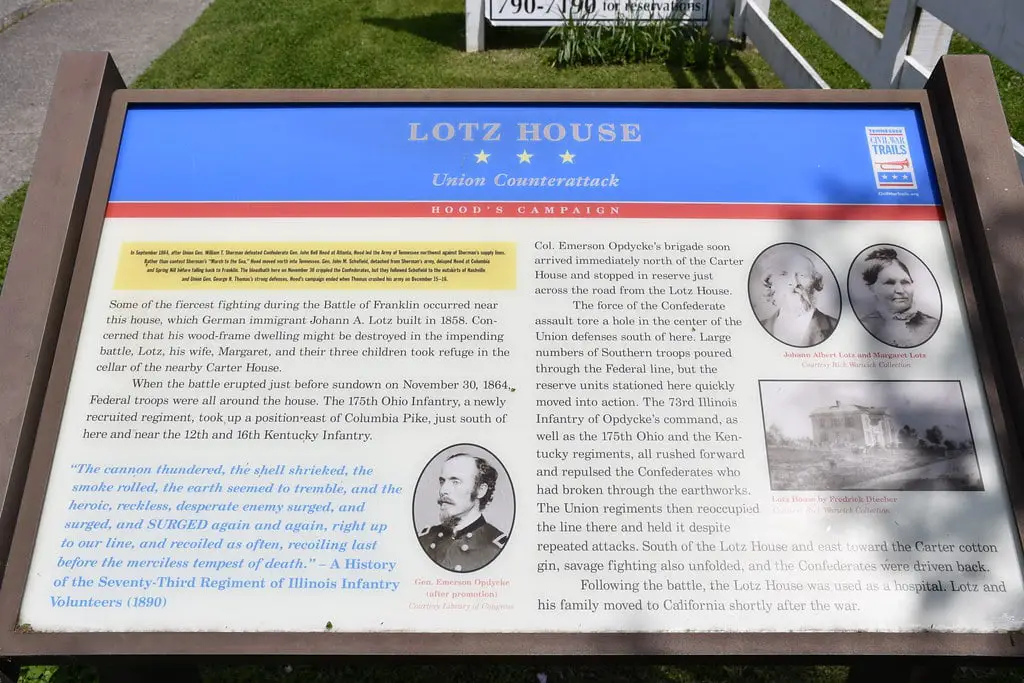

Five Hours That Tore the House Open

At 2 p.m. on November 30, 1864, Confederate troops came across open fields toward Franklin.

About 20,000 of them moved in a line two miles wide.

Union forces, blocked by the Harpeth River and unable to retreat to Nashville, had taken up defensive positions using makeshift trenches and barricades that crossed the properties of both the Carter and Lotz families.

Johann Lotz saw the lines from his yard and knew the house couldn't protect them.

He grabbed what tools he could carry and moved his family across Columbia Pike to the Carter House.

They took shelter in the brick basement, along with the Carter family.

What followed was five hours of close-quarters combat.

Artillery tore into the town. The Lotz House, still new by any measure, was hit from the south.

A cannon shell blasted through a wall. Other shots burned holes into the roof and floorboards.

By nightfall, more than 10,000 soldiers were dead, wounded, or missing. Six Confederate generals were among them.

When the Lotz family stepped back into their home, they saw blood, splinters, and plaster across their furniture and staircase.

The house had held up, but barely. It had no cellar. It had no defenses.

The war passed quickly, but the damage lingered. The Lotz House was patched up enough to be used as a field hospital almost immediately.

Repairs came fast. Too fast, in Lotz's view. He didn't like the rushed woodwork and said so plainly.

Market Exit After the War

The Lotz family stayed in the house for several years after the war ended.

Franklin didn't burn, but it didn't recover quickly either.

Albert Lotz returned to woodworking. Matilda, his daughter born in the house in 1858, had already started drawing animals before the battle.

She kept drawing after it.

At some point in the late 1860s, Lotz built a piano.

On it, he carved an eagle. One claw gripped an American flag held upright. The other held a Confederate flag pointed downward.

The message wasn't hidden. Word got around quickly. Threats followed.

In a town where Confederate veterans still gathered, this wasn't read as a neutral symbol.

Lotz sold the house and most of its contents. The sale was rushed and unprofitable.

He packed the family into a wagon and left Tennessee behind, heading west.

They ended up in San Jose, California.

After they left, the house cycled through owners and purposes.

At various times, it held an attorney's office, a bakery, a gift shop, a flower store, and even an apartment complex.

At one point in 1974, the house was rebranded as a Halloween haunted house.

From Preservation Gamble to Museum Ledger

By the early 1970s, the Lotz House sat stripped of its past uses but full of wear.

Paint flaked off its siding. The rooms that once displayed piano cases and carved mantels had been sliced up for business tenants.

Some walls had modern wallpaper. Others had mold.

In 1974, when the Heritage Foundation of Franklin and Williamson County stepped in, the offer was $25,000.

They paid it to keep the place from being bulldozed.

The foundation cleaned up the exterior and put the brakes on further decline.

Inside, changes came slowly. For a while, a gift shop operated in the front rooms.

Ownership passed again before J.T. Thompson, a local preservationist, bought the property in 2001.

He reached out to David Lotz, a great-great-grandson living in California, and collected family material, right down to how the name was supposed to be pronounced.

By 2008, the house reopened as a museum. The artifacts inside were local. Civil War items.

Mid-19th-century furniture. The display leaned into the building's wartime role without staging it for drama.

Some of the cannonball holes were still visible in the floors.

Other spots had been carefully repaired.

Since the mid-2000s, more land around the battlefield has come under conservation.

The Carter Hill Battlefield Park reclaimed sections once lost to housing and retail.

Over $19 million went into that effort, pushed by local historians and backed by donors.

The Lotz House now works in step with that reclaimed ground.

Museum Hours, Tickets, and the Business of Memory

The Lotz House opened as a museum in 2008.

The idea had kicked around for years, but once the walls were steady and the ownership secure, they put it to work.

Tours run daily. The layout stays honest - no velvet ropes or heavy interpretation.

Just original floors, damaged walls, and whatever relics survived the last 160 years.

Doors open at 9:00 a.m. Monday through Saturday, with a shorter Sunday window from 11:00 to 4:00.

The format is a guided walk and listen. Stories come from the wood, the tools, the scars.

Guides fill the gaps with maps, accounts, and what's been recovered from the yard and nearby fields.

Add-ons exist. There are ghost tours, battlefield tours, and a women's history tour that re-centers the narrative.

The Lotz House Museum runs as a nonprofit. No corporate backer, no retail wing. What it earns gets folded back into preservation and staff.

Its placement on Columbia Avenue does the rest - right next to Carter House, walking distance to Carnton.

Foot traffic takes care of itself.

This isn't polished history. It's a building patched up after being shelled. They don't hide the seams.

Paranormal Bookings and Broadcast Leverage

In 2010, the Travel Channel showed up. "Most Terrifying Places in America." Episode 6. The Lotz House cut.

War ghosts, flickering lights, cold rooms - the usual inventory, told through TV pacing - viewers bit.

Interest spiked. Franklin got a bump.

Eight years later, they came back. "Haunted Live." Same network.

This time, the Tennessee Wraith Chasers took over, using live cameras, on-air prompts, and night vision.

The house played along.

The episode leaned into claims already familiar in town: footsteps on the stairs, voices in empty rooms, doors that didn't stay shut.

The museum didn't flinch. It folded the noise into its after-hours slate. Ghost tours launched.

Nothing theatrical - no fake blood or jump scares - just a walk through darkened rooms with a story guide and a stack of wartime facts.

Some came for the history. Some came hoping to see a shadow move.

The daytime tours stayed unchanged.

Still focused on 1864 and still grounded in the five-hour battle that tore the place apart.

But after dark, the draw widened. Paranormal talk filled the gaps left by formal history. The walls held both.

By then, Franklin's tourism sector had learned how to work with that mix.

Civil War buffs and ghost chasers could spend money in the same gift shop.

The old house at 1111 Columbia Avenue handled both crowds without blinking.

🍀