The Hotel That Refused to Disappear

A lot of buildings in downtown Mobile have come and gone.

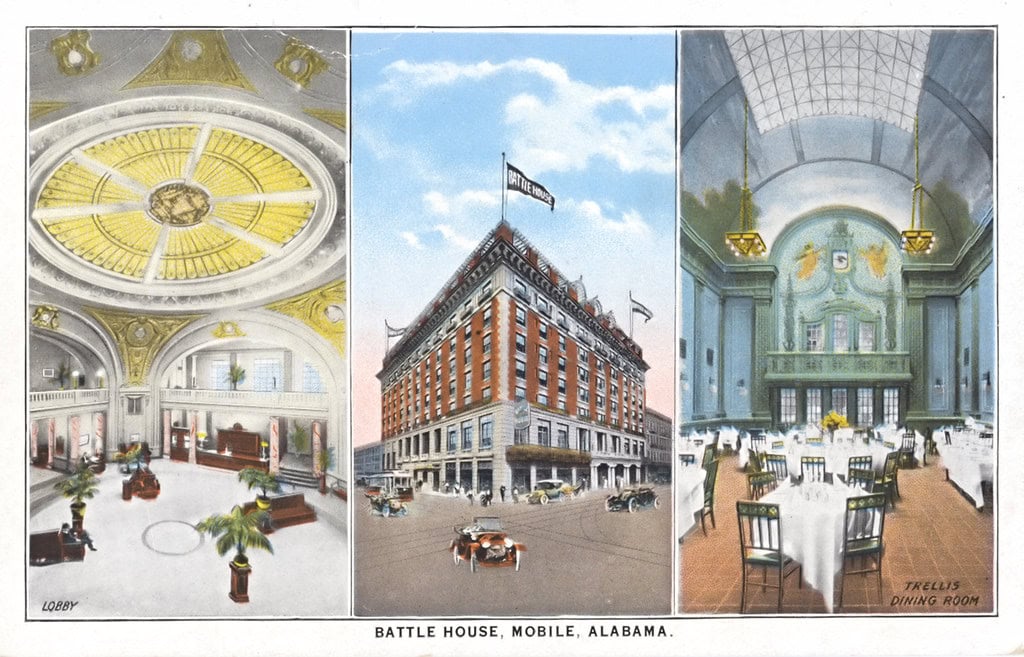

The Battle House Hotel didn't. It stood, burned, stood again, then sat empty for thirty years - too solid, maybe, or too stubborn to be erased. From the street, it still looks like something meant to stay.

Built in 1908 and reopened in 2007, it has been more than one thing in more than one era. For those tracing things to do in Mobile, Alabama, the Battle House Hotel pulls a longer thread.

Ground Leases and Ground Zero

Long before the Battle name went up in letters, this corner of North Royal Street was already carved into the city's history.

The site had served as a military headquarters under Andrew Jackson during the War of 1812.

After that, hotels kept appearing and burning down.

The Franklin House came first in 1825, followed by the Waverly Hotel in 1829.

Both were gone by the time James Battle and his two half-nephews - John and Samuel - arrived with plans for a longer-lasting structure.

They opened the original Battle House Hotel on November 13, 1852.

The layout was ambitious for the time: four brick stories, 200 rooms, and a two-level cast iron gallery.

The location mattered. Cotton was king, and Mobile was flush.

Wealth passed through on the way to New Orleans or Savannah, and the Battle House Hotel caught its share.

By the end of the century, it had a National Weather Service station and electric lights.

Renovations followed in 1900. Four years later, the whole building burned.

None of that structure remains. But its footprint does. So does its name.

Steel, Smoke, and Floorplans

After the fire took the first Battle House Hotel in 1905, the owners moved fast.

They hired Frank Mills Andrews, a New York architect whose work leaned into steel and concrete instead of wood and plaster.

The new structure opened in 1908, eight stories tall and Georgian Revival in style.

By Mobile standards at the time, it was heavy construction.

Alabama hadn't seen many steel-frame buildings yet.

The hotel stayed open through both world wars. In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson came to town and stayed there.

The line he delivered while at the Battle House - "The United States will never again seek one additional foot of territory by conquest" - made the newspapers.

That visit helped the hotel's reputation. It already had marble trim, a domed skylight, and a location that caught traffic from the docks.

The 1916 renovation brought updates, though the bones stayed the same.

More work came in 1949, when air conditioning went into all rooms and public areas.

That wasn't common yet in the Gulf South, but the Battle House had the money and installed it anyway.

By mid-century, it had weathered fires, yellow fever, and long, hot summers.

The branding didn't change. Mobile knew what the name meant.

The floorplan hadn't shifted much either - lobby below, rooms stacked above, ballroom tucked to one side.

What did change was the ownership. In 1958, Sheraton Hotels bought it and ran it for ten years.

They called it the Sheraton-Battle House Hotel.

Vacancy and Value Loss

Sheraton sold the Battle House Hotel in 1968 as part of a wider portfolio sale that included 17 aging hotels.

Gotham Hotels took over next. They didn't keep the Sheraton name. They didn't keep the momentum either.

The building had seen its best days as a passenger hub, but rail travel was fading, and nearby port activity had slowed.

Business dropped. By 1973, a group of local buyers stepped in, rebranding it as the Battle House Royale.

They talked about a full renovation.

The plans didn't stick. The hotel closed in 1974.

By 1975, it had been added to the National Register of Historic Places, but that didn't move any contractors.

No work crews showed up. The property stayed shuttered for nearly three decades.

From the outside, it still looked like the Battle House Hotel, but the inside was decaying.

The Crystal Ballroom went dark. The Trellis Room was stripped. By 1980, it was the only intact building left on its city block.

Ownership didn't change during those years. There wasn't much to sell - no bookings, no active permits, no operating license.

The location was still central, and the bones were still good, but nobody was lining up to turn the key.

That shifted in 2003, when Retirement Systems of Alabama stepped in.

They didn't just plan to revive it. They added a skyscraper next door.

It was the first serious move since the 1940s. The value had been buried under thirty years of vacancy.

Someone finally started digging it out.

Reinvestment and Reentry

In 2003, the Retirement Systems of Alabama moved in with capital and a development plan.

They brought Smith Dalia Architects out of Atlanta and paired them with TVSA for the new tower.

The job wasn't cosmetic. The Battle House Hotel had sat empty for 29 years.

Interior walls had crumbled, wiring was obsolete, and the mechanical systems hadn't been touched since the 1960s.

What was salvageable had to be reinforced. The dome in the lobby stayed. So did the marble floors. Most of the rest was rebuilt.

The adjoining RSA Battle House Tower went up alongside it.

At 745 feet, it became the tallest building in Alabama when completed in 2007.

The lower floors of the tower included new hotel rooms - spillover capacity that connected back to the Battle House Hotel through shared facilities and service corridors.

The placement was deliberate. Ground-level access gave both buildings mutual visibility from Royal Street and St. Francis.

Restoration of the original structure focused on era-specific elements.

The Crystal Ballroom was returned to its 1908 color scheme, with restored plasterwork and lighting to match.

The Trellis Room, now a restaurant, added a full-view kitchen and seating for 90.

The barrel-vaulted ceiling and Tiffany glass skylight remained.

The goal wasn't nostalgia for its own sake.

It was more practical than that - turn a dead asset into a working one, with historical branding still intact.

The hotel reopened on May 11, 2007, under Marriott's Renaissance brand.

That gave it global booking access without replacing the name.

Locals still called it the Battle House Hotel.

Assets in Marble and Paint

The building on 26 North Royal Street doesn't hide what it is.

The exterior carries over the 1908 lines: brick and marble cladding, paired Tuscan columns at the portico, recessed loggias above, and cast iron balconies curling across the higher floors.

A molded cornice caps the roofline. These aren't add-ons. They're built into the structure. The façade hasn't been flattened or stripped.

Inside, the most visible holdover is the domed skylight at the center of the lobby.

The ceiling and walls use trompe-l'œil painting to create depth.

Framed portraits of George Washington, George III of Britain, Ferdinand V of Castile, and Louis XIV of France line the walls - an odd grouping, but they've been there since the 1908 opening and were restored rather than replaced.

None were chosen at random. Each point is a power structure once relevant to Mobile.

The Trellis Room remains the hotel's restaurant, serving northern Italian dishes from an open kitchen.

It holds a four-diamond rating and doesn't use the ballroom for overflow.

That's reserved for weddings and Mardi Gras balls, which use that track back to the building's earliest years.

The first recorded Mardi Gras event at the site was The Strikers Ball in 1852, long before the term "Battle House" meant anything.

The building now functions in two registers.

It serves modern commercial purposes - lodging, dining, event space - but it also acts as an archive of its transactions.

Restoration kept both layers in place. Neither one dominates.

🍀