A Mall Rises from Lima Bean Fields

In March 1967, South Coast Plaza opened on ground that had been a working lima bean field. The Segerstrom family, long tied to farming in Costa Mesa, turned the land into a commercial center that was ready for the new suburban growth of Orange County.

The first anchors were May Company, which had debuted in late 1966, and Sears. Both names carried weight at the time, pulling steady traffic to the site.

Victor Gruen Associates shaped the early look of the property. Gruen had built a reputation as an architect of shopping centers, and his design gave the mall its first footprint.

What stood out was the timing. Fashion Island in Newport Beach, developed by The Irvine Company, was rising the same year, and the two malls were positioned to compete for the region's shoppers.

The choice of location mattered. The construction of Interstate 405 provided a straight route linking Los Angeles and San Diego, and South Coast Plaza was situated right beside it.

This made the new center a convenient stop for drivers traveling along the freeway. It also tied into the suburban push of the late 1960s, when housing tracts and office complexes were spreading rapidly.

For anyone looking at things to do south of Los Angeles, CA, the mall instantly became part of the list.

The Joseph Magnin store at South Coast Plaza opened in March 1968, in the Carousel Court. Architect Frank Gehry designed the two-story building.

Expansions That Redefined Scale (1970s–1980s)

By the early 1970s, shoppers pouring through May Company and Sears found more waiting for them at South Coast Plaza.

In 1973, Bullock's opened in a new wing designed by Welton Becket, its crisp lines signaling that the mall was already outgrowing its first phase.

Four years later, I. Magnin followed, its space with the kind of angles and flair that drew as much attention as the goods inside.

The real breakthrough came in 1978.

Nordstrom cut the ribbon on its first store outside the Pacific Northwest, and the event hinted at the national reach the chain would one day achieve.

The following year, Saks Fifth Avenue joined, bringing its customer base into the mix.

Together, these stores shifted the center's profile from suburban retail stop to a place that could rival downtown shopping districts.

By 1986, the momentum carried further. Nordstrom doubled its footprint with a new store, twice the size of the original.

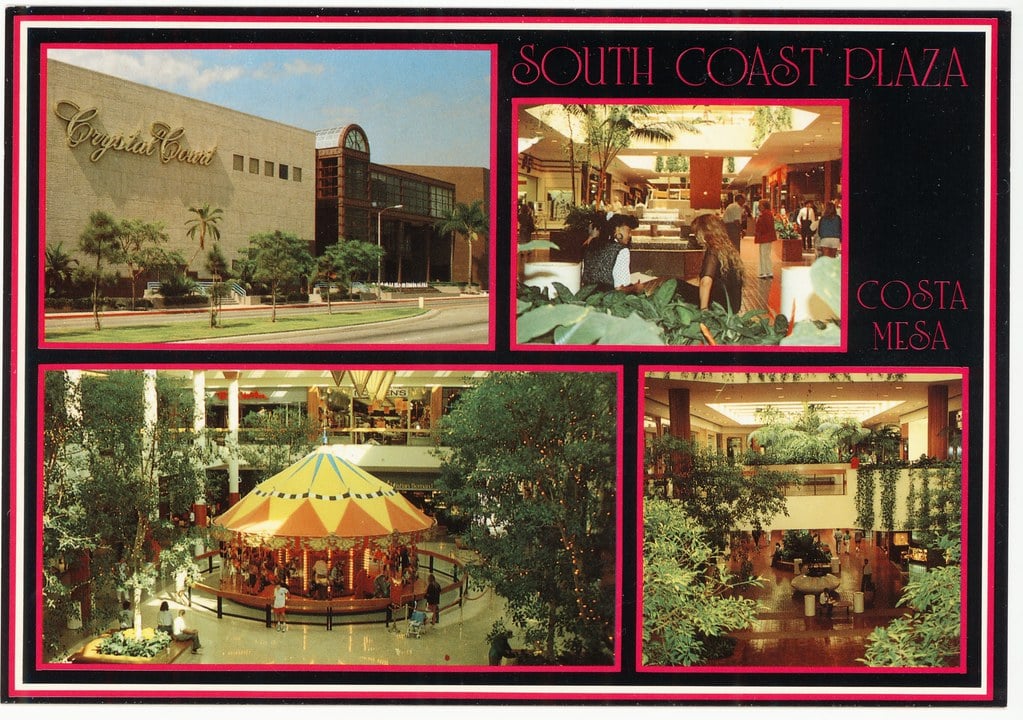

Across Bear Street, Crystal Court opened with The Broadway and J.W. Robinson's, both of which were willing to split their sales from Fashion Island because South Coast Plaza's draw had become that strong.

In 1988, Tiffany & Co. moved in, its glass cases and signature blue boxes sealing the mall's reputation as a destination.

Shifts in Anchor Stores and Ownership (1990s–2000s)

The 1990s brought a wave of consolidation, and the mall adjusted with each change.

In 1991, the I. Magnin space closed and reemerged as Bullock's Men's, catering to a narrower slice of the market.

Just two years later, May Company and Robinson's merged into Robinsons-May, leaving two full-line stores standing side by side.

In 1996, the names on the façades shifted again.

Federated Department Stores folded Broadway and Bullock's into the Macy's brand, turning South Coast Plaza into a rare center with multiple Macy's under one roof.

Bloomingdale's had been in talks to join the lineup as early as 1995, but resistance from other anchors delayed the move.

Instead, the early 2000s brought construction.

In 2000, the Segerstrom family financed a $100 million project that linked Crystal Court to the main building through a 600-foot pedestrian span called the Bridge of Gardens.

The west wing took on a new focus - home furnishings anchored by Macy's Home and Furniture, with Crate & Barrel, Borders, and Sport Chalet filling large spaces once held by department stores.

When Robinsons-May closed in 2006 after its merger with Macy's, the cycle turned once more.

A year later, Bloomingdale's finally opened in the original May Company site, giving South Coast Plaza another national name.

Through all of these shifts, the Segerstrom family held on to ownership, keeping the center out of the hands of real estate investment trusts that controlled so many other malls of its scale.

Design, Art, and Architecture as Identity

The escalator rose into a space that didn't behave like a store. Walls didn't line up.

Corners turned into planes, in the I. Magnin Wing, opened in 1977, the building bent around itself. The light didn't settle; it caught edges and shifted.

For a while, people came to see the space as much as what was sold inside it.

That same year, the old Sears exterior, once flat and unbothered, began to disappear behind concrete rework.

The mall was pulling itself forward. It kept doing that.

In 1982, Noguchi's "California Scenario" opened outside the shopping loop: six granite boulders, a trickle of water, and no signs explaining any of it.

Office workers passed through it with coffee. Kids climbed the sandstone.

Crystal Court came in 1986. Inside, the chandeliers hung in hard shapes, pyramids flipped upside down, heavy with glass.

The escalator atrium, three floors high, echoed the proportions of Egyptian ruins.

But here, everything gleamed.

In 2000, Kathryn Gustafson laid out the Bridge of Gardens, a walkway connecting Crystal Court with the rest of the mall.

It wasn't dramatic. Just low planters, stone underfoot, and a stretch of quiet between buildings.

Six years later, $30 million covered what was left of the old finishes.

Brass turned to bronze. Tile became marble.

South Coast Plaza as a National Luxury Hub

The line outside Zara stretched past Carousel Court. Inside, the first shoppers pushed through in clumps.

That was 2004, Zara's California debut. Fast fashion, packed shelves, new every week.

It was a different kind of urgency.

A year later, Chloé opened next door. No music. No clutter. Just white space and a sales team that didn't rush. Rolex followed.

Then, Room & Board filled out a full anchor slot, 40,000 square feet of furniture placed with too much room between them all.

The mall had found a rhythm: tight openings, clean floors, no public statements.

It wasn't just busy. It was built to sell. Around 270 stores. 2.8 million square feet.

Foot traffic is pushing 24 million. Anchors stayed: Sears, Macy's, Bloomingdale's, Nordstrom, Saks.

But they were no longer the point.

By 2007, the mall started treating restaurants like tenants.

Fashion Plates, a sort of Restaurant Week, ran for ten days. Prix fixe menus. Tables that turned like a product.

You could eat a two-course lunch after trying on silk at Hermès. Then go back. It all stayed inside.

Flagships, Closures, and New Retail Power (2019–2024)

When Furla opened its California flagship in 2019, the storefront was quiet, white, and full of mirrors.

It came just two days after the last original anchor, Sears, locked its doors for good.

The final day was January 1, 2019. After 52 years, the lights shut off and the escalators stopped moving.

Din Tai Fung had opened in the Sears wing back in 2014, while the anchor still operated.

After the closure, people started calling it the Din Tai Fung wing.

Retail picked up again in 2021. Thom Browne, Ganni, Loewe, and Louis Vuitton California Dream opened in quick succession.

Sock Harbor, Untuckit, and Psycho Bunny followed, all smaller but built for volume.

Nectar Bath Treats took a storefront near Bloomingdale's, scent trailing out into the hallway.

Then came the flags. Balmain opened its flagship in late 2023.

A few weeks later, Balenciaga took two stories and more than 9,000 square feet. They used concrete floors, tall glass, and shadowed lighting.

In early 2024, thirty new brands were announced. Amiri, Alaïa, Mejuri, Santa Maria Novella.

2025: Leasing Surge and the Village Plan

By May 2025, the leasing office had signed over 20 new tenants. Dior Beauty opened a West Coast flagship.

Guerlain followed. Moncler, Roger Vivier, and Gianvito Rossi sent contractors ahead of opening dates.

Eres and Sandro went in near Bloomingdale's. Vox Kitchen and Ramen Nagi opened days apart.

The temporary Tiffany & Co. boutique, set in a stripped-down glass box, was the only one that didn't feel permanent. It pulled in customers anyway.

Behind the leasing push was a shift already underway.

Across Sunflower Avenue, on 17 acres known as South Coast Plaza Village, the owners submitted plans for a new development.

C.J. Segerstrom & Sons filed the paperwork in coordination with Hines.

The proposal called for 1,583 residential units. Up to 300,000 square feet of office. Around 80,000 square feet of street-level shops and restaurants.

Seven and a half acres set aside as public space, with the rest planted or shaped into courtyards. They called it The Village Santa Ana.

South Coast Plaza in Costa Mesa, CA holds a scale few centers in the country can match.

With over 270 retailers, it has the highest concentration of design fashion stores in the United States.

Sales average around $800 per square foot, nearly double the national figure of $411 and just behind Westfield Valley Fair in San Jose-Santa Clara at $809.

The anchor lineup reinforces its size and pull, with three Macy's stores, Nordstrom, Bloomingdale's, and Saks Fifth Avenue all under the same roof.

Altogether, the 2.8 million square foot complex ranks as the largest shopping mall in California and the sixth largest in the United States.

It used to be a great shopping time when there were normal fashion stores that normal people could afford. Sadly, no more..... all you see are very high-prized snooty designers. Are there really that many very rich people to sustain this outlook?

For those who remember the mall of the 1970s and 80s, that pivot can feel like a loss. It became a showcase of wealth at the expense of accessibility.

Frank Gehry designed Joseph Magnin that opened in1967 (not I. Magnin which opened later..)

Thank you for pointing that out. The Joseph Magnin store was indeed Gehry's retail work.