At first glance, the building didn't look like it could accommodate a full trainload of New Yorkers in Florida, but that's exactly what happened.

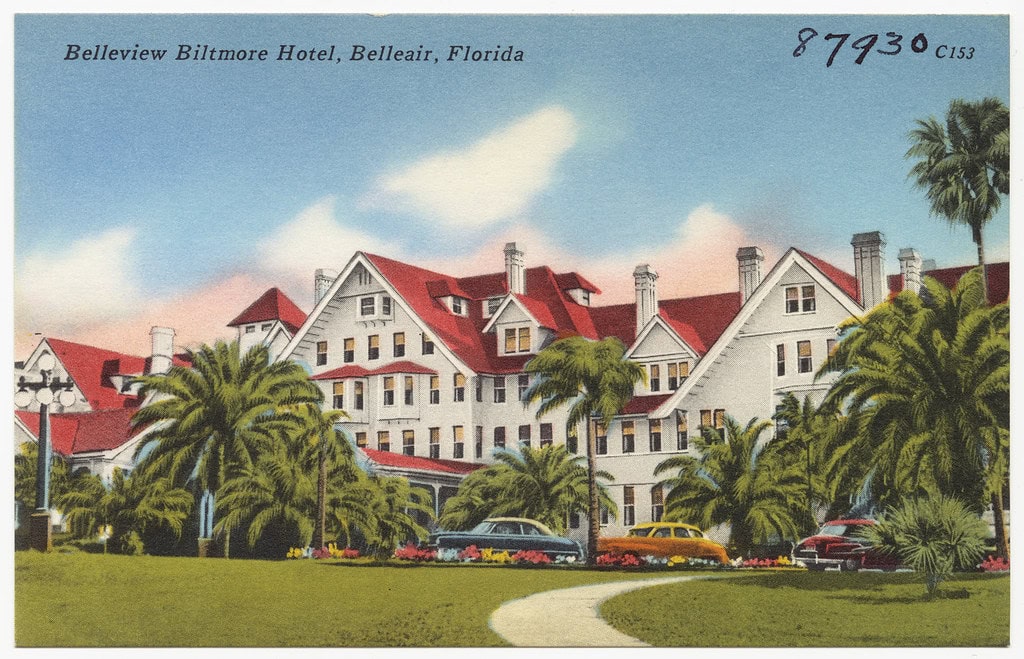

When Henry B. Plant opened the Belleview Hotel in January 1897, he didn't just add another stop to his railroad network - he built a wooden giant with views across the Gulf of Mexico and designed it to last.

For more than a century, this hotel drew guests through its wide, wood-framed doors: baseball players in wool uniforms, U.S. Presidents stepping off private cars, and tourists in search of winter sun.

Even now, after most of its original structure has been removed, the remaining wing still tells a version of the story - if you know what to look for.

You wouldn't expect to find one of the last Gilded Age resorts on Florida's west coast, tucked into a quiet stretch of Belleair. But there it was.

Construction, Railroads, and the Gilded Age Gamble

The Belleview Hotel opened on January 15, 1897. Henry B. Plant had it built the previous summer.

At the time, he controlled one of the largest transportation networks in the southeastern United States - Plant System railroads.

The Belleair location was meant to anchor winter tourism along Florida's Gulf Coast, using rail service as the main delivery tool.

Trains pulled in from as far away as New York.

In 1902, the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad absorbed Plant's company.

It continued the tradition, running the Pinellas Special - train numbers 95 and 96 - straight to a siding right on the hotel's grounds during the 1920s.

That wasn't common. Having direct train service to a resort gave Belleview an edge over newer competitors.

The building itself was large - 350,000 square feet by the mid-20th century - and at one point, it was the second-largest occupied wooden structure in the country, behind only the Hotel Del Coronado in San Diego.

Its architectural style blended Queen Anne and Shingle elements.

Inside, the finishing touches - Tiffany glass, handcrafted staircases, and native Florida heart pine - gave it a distinct identity.

Visitors arriving at the station didn't see the beach right away.

But they could see the wide verandas, sloped green roof, and tall white structure sitting high above the coast.

It was built on one of the highest points in Pinellas County, and the views stretched to the barrier islands off the Gulf.

This part of Belleair, Florida, doesn't look like it was ever meant to be a hub.

But back then, it was - especially for people looking for things to do in Florida, during the cold months up north.

Challenging Times and Mid-Century Decline

By the time the United States entered WWII, the Belleview-Biltmore Hotel had already experienced several transitions.

After the Plant family exited in 1918, the property landed with the Bowman Hotel group.

The rebranding to Belleview-Biltmore Hotel came in 1926 under their ownership.

During WWII, the hotel shifted from vacationers to military housing.

Servicemen from MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa used it as temporary lodging.

The battle years changed its pace, but the hotel returned to seasonal business after 1945.

Ownership changed again - Bernard F. Powell took over the operation during the recovery years.

It wasn't a flashy handover, but it marked the start of a long stretch when the building's age began to matter.

Travel habits were changing. Motels started opening closer to the shoreline.

Tourists wanted beach access and didn't need a giant wooden hotel set a few miles inland.

In the 1970s and 1980s, that gap became a problem. Occupancy dropped, and maintenance lagged. For a time, only part of the structure was kept in active use.

In April 1976, Bob Dylan and his Rolling Thunder Revue rehearsed at the Belleview-Biltmore Hotel.

They then took over the Starlight Ballroom, and Dylan played two shows there on the 22nd.

He wasn't alone - Roger McGuinn, Joan Baez, and Scarlet Rivera were among the performers on-site.

That brief music history moment didn't change the hotel's business trajectory, though.

The building continued to wear down.

By the end of the 1980s, some floors had already been closed off.

Although its location hadn't changed, in a market dominated by new construction, it no longer stood out.

The parts that made it memorable - woodwork, scale, and design - required upkeep that few owners were willing to handle.

Foreign Investment and Preservation Setbacks

In the early 1990s, ownership passed to Mido Development, a Japanese company that renamed the property the Belleview-Mido Resort Hotel.

They made repairs and added new spaces, including a pagoda-style lobby and an expanded patio.

That design choice didn't sit well with preservation advocates.

It clashed with the original Queen Anne and Shingle Style architecture.

Even with improvements, Mido faced financial trouble.

By 1994, the business was under pressure. Repairs stalled, and the top three floors were shut down and left in disrepair.

In 1997, Salim Jetha stepped in as the new owner. That shift didn't reverse the long-term issues either.

Between 2001 and 2004, efforts were made to restore some common areas and guest rooms.

But two hurricanes - Jeanne and Frances - brushed through in the summer of 2004.

They didn't flatten the building, but they took a heavy toll on the roof.

Water damage complicated ongoing renovation plans.

At that point, the idea of fully restoring the structure started to slip further out of reach.

Later that year, DeBartolo Development Group proposed demolishing the hotel and building retail and condo units.

The public reaction was strong. The plan was pulled in early 2005, but they kept pushing and refiled a demolition permit that spring.

The application was submitted to the Town of Belleair. Preservation advocates pushed back again.

They cited other restorations - the Hotel del Coronado in San Diego and the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island - as working models and argued that the Belleview-Biltmore Hotel had comparable bones.

But each passing year brought higher costs and more damage. The longer it sat, the harder the case became.

Closing Doors and Legal Pressure

In January 2009, managers of Belleview-Biltmore Hotel announced the property would close at the end of May.

The plan was ambitious on paper: a three-year, $100 million renovation.

But after the doors closed that summer, nothing started.

Legal challenges from nearby residents slowed every step.

They objected to parts of the redevelopment proposal, raising concerns about density, traffic, and zoning limits.

By November, the hotel faced new pressure from the local code board.

Officials in Belleair issued a ruling to fine the owner $250 per day due to the deteriorating roof.

Photos at the time showed warped wood and open seams.

Maintenance crews had placed temporary covers after hurricane damage in 2004, but no long-term fix had been done.

In 2010, Legg Mason Real Estate Investors pulled out of the project, opening the door to new buyers.

The Ades brothers, developers from Miami, acquired the hotel in 2011.

Unlike previous buyers, they didn't present a renovation plan.

Instead, they submitted proposals to demolish the structure and build up to 180 townhomes on the site.

By early 2012, the city of Belleair signaled a willingness to approve demolition.

One last push to save the property surfaced in 2013.

Belleview Biltmore Partners LLC entered negotiations to lease and buy the site.

They also sought control of the adjacent golf club. Their pitch focused on full restoration.

Richard Heisenbottle, a preservation architect working with the group, argued that the hotel could still be repaired and reopened.

His designs aimed to bring back much of the original layout, with modern updates tucked beneath new spa spaces and garages.

But by that point, structural issues, legal disputes, and market forces had all heavily weighed against the idea.

Boutique Rebranding and Physical Relocation

In 2014, JMC Communities stepped in with a different proposal.

They filed plans to demolish the hotel - almost all of it - but preserve the oldest section.

This part of the building, roughly 38,000 square feet, was the western wing built in 1897.

That came to about 10% of the total structure by footprint.

Local officials approved the plan. Before demolition started, workers documented the site with photos and written records.

The actual teardown began on May 9, 2015. JMC's plan called for 132 new units, a mix of townhomes and condominiums, on the cleared space.

Some original materials were salvaged to use inside the reduced version of the hotel.

The Friends of the Belleview-Biltmore Hotel and state preservation groups filed lawsuits to block the demolition, but the lawsuits didn't advance.

By December, all legal objections were withdrawn.

The preserved part of the building was moved on December 21, 2016.

Crews lifted it onto hydraulic dollies, rotated it 90 degrees, and rolled it 375 feet east.

The structure was then placed on a new foundation.

After that, it lost its place on the National Register of Historic Places.

Though the preserved portion reflected 70% of the 1897 footprint, after relocation, it no longer met registry criteria.

Restoration work took two years. By December 5, 2018, the Belleview Inn opened.

This version operated under different rules. Commercial limits in Belleair restricted the scale of amenities.

The Inn didn't have the ballrooms, restaurants, or conference wings that once supported the original hotel.

Instead, it ran as a lodging property, using salvaged glass, wood, and trim from the original interior.

dont know we're the gulf of Mexico in the story comes from but it's gulf or America libtards .

In 1897, guests at the Belleview‑Biltmore Hotel looked out over the Gulf of Mexico. That's the name they used at the time.