The desert's most persistent story

In southeastern New Mexico, a desert town carries a story that never seems to settle. In the summer of 1947, something fell from the sky near Roswell. Ranchers described unusual debris, and for a short moment, the military confirmed it had recovered a flying disc.

Within a day, that statement was replaced by an explanation about a weather balloon. The correction did little to quiet the rumors.

Over the decades that followed, Roswell became shorthand for secrecy, cover-ups, and the possibility that humans were not alone.

To walk through downtown Roswell now is to see a community that has embraced its strange inheritance. Streetlights are capped with painted alien heads. Motels advertise with flying saucer logos.

At the center of it all stands the International UFO Museum and Research Center, the most visible attempt to preserve and present the mystery that has defined the town.

A museum born from testimony

The museum did not start as a commercial gimmick. It grew out of the determination of three men with close ties to the original events.

Walter Haut, who had issued the Army's first announcement of a recovered disc, Glenn Dennis, a mortician who claimed to have received unusual requests that summer, and Max Littell, a local businessman, pooled their efforts in the early 1990s.

They opened the doors in 1992 inside a former movie theater on Main Street. Their intention was not to settle the debate but to create a record.

They wanted visitors to see the affidavits, photographs, and clippings for themselves.

It was a way of keeping testimony alive in a country where official accounts had shifted more than once.

What greets visitors

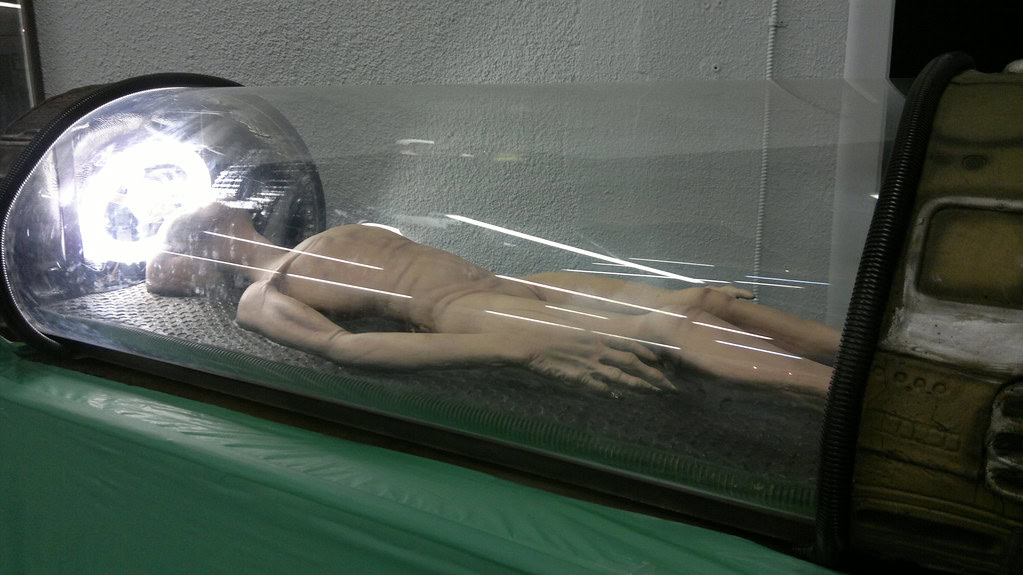

The lobby feels almost like a joke. Carved aliens grin at the door, souvenir machines clatter, and families take turns posing with fiberglass greys.

Kids laugh, parents roll their eyes. It could be any roadside stop in the desert.

Then the mood turns. A wall of brittle newspaper clippings lines up the summer of 1947 day by day.

Next to them, affidavits from ranchers and nurses describe bodies and wreckage. A sheriff's faded portrait hangs nearby.

None of it is explained or resolved. Visitors read, frown, and move on.

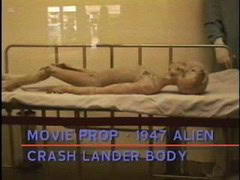

Deeper inside, the contradictions multiply: Area 51 maps, abduction sketches, looping footage of the alien autopsy once sold as real.

A quiet research library waits at the back, holding thousands of files.

By then, the carnival atmosphere has drained away. International UFO Museum leaves people with a puzzle and no clear way to solve it.

An archive in the desert

Behind the souvenir shelves and fiberglass displays is the part of the International UFO Museum that few tourists notice.

A plain doorway leads into the research library, a room lined with metal shelves and filing cabinets.

Inside are more than seven thousand books and tens of thousands of clippings, letters, and declassified reports. The air smells of dust and cardboard.

This is where the museum becomes something more than a roadside stop. Graduate students sort through Cold War files.

Local teenagers lean over photocopies for history projects. Journalists flip through affidavits written in shaky cursive.

The staff does not tell anyone what to believe. They only point to where the papers are stored.

In Roswell, a town best known for plastic green men on motel signs, the library feels almost out of place.

It is quiet and methodical, a reminder that behind the spectacle lies a long record of people trying to explain what they saw.

The pull of Roswell

The International UFO Museum quickly became a cornerstone of the town's economy. It welcomes about 220,000 visitors a year, and in late 2023, it marked its 5 millionth guest.

Families on road trips stop in, UFO enthusiasts treat it as a pilgrimage site, and international travelers fold it into itineraries across the American Southwest.

Roswell leans into that attention. The annual UFO Festival, held each summer, features costume contests, lectures, and parades.

Local businesses thrive on alien branding, from fast food restaurants shaped like saucers to souvenir shops filled with green figurines.

The museum sits at the center, providing context and credibility amid the carnival atmosphere.

The questions it raises

The museum never offers a single version of events. A typed Army statement explains that a weather balloon came down in the desert.

Just a few feet away, affidavits describe bodies carried away under canvas and wreckage that locals said would not break.

The stories are displayed together without commentary.

People stop and read in silence. Some take photos, others shake their heads. There is no guide to tell them which account is credible. The contradiction itself becomes the exhibit.

For skeptics, the mix of rumor and record feels careless. For believers, it is the first time the voices of ordinary townspeople are treated as evidence.

What stays with visitors is not an answer but the unease of two histories that cannot be made to match.

Why do people keep coming?

Interest in Roswell has not dimmed. In recent years, Pentagon reports on unidentified aerial phenomena have put the subject back in the mainstream.

Streaming series and films return regularly to the theme of the desert crash.

The museum bridges those waves of attention with the lived history of a small town that became a symbol of secrecy.

For some visitors, the stop is lighthearted fun, a chance to collect pressed pennies and pose with plastic aliens.

For others, it is a serious reminder of how one incident reshaped public trust in institutions.

The museum holds both roles at once. It offers a record of the past while also embodying the town's embrace of its strange identity.

In Roswell, the question of what fell from the sky in 1947 may never be answered to everyone's satisfaction.

But inside the International UFO Museum and Research Center, the question is allowed to remain open, and that may be why people continue to walk through its doors year after year.