The Asylum on the Hill - Real Estate, Deals, and Development

The wind rolled off the Hudson River on October 18, 1871, carrying the first chill of autumn as 40 patients stepped onto the hospital grounds.

They were the first to walk through its heavy wooden doors, past iron gates that clanged shut behind them.

The Hudson River State Hospital for the Insane, perched on 296 acres of donated land just north of Poughkeepsie, was open for business.

New York had been running out of room for the mentally ill. By the 1860s, the state's only asylum, Utica Psychiatric Center, was overflowing.

Governor Reuben Fenton ordered a five-member commission to find land for a second hospital - somewhere between New York City and Albany, where it could serve both rural towns and the growing metropolis.

In January 1867, the commission presented its solution: a vast stretch of farmland once owned by James Roosevelt and William A. Davis.

Dutchess County elites offered it up for free, eager to bring a project of this scale to their backyard. The state agreed.

The design was ambitious. Architect Frederick Clarke Withers was hired to bring the Kirkbride Plan to life - an asylum model in which fresh air and open space were thought to cure mental illness.

His plan stretched the main building over 1,500 feet, with two wings that branched off like arms, separating male and female patients.

The grounds were entrusted to Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the same men behind Central Park.

The idea was simple: patients would heal faster in a place that resembled a grand estate rather than a prison.

Reality hit fast. Construction began in 1868 with an $800,000 budget, but costs spiraled almost immediately.

A private dock had to be built along the Hudson just to receive shipments of stone and lumber.

Southern yellow pine was imported for the floors. Water was pumped uphill from the river into a custom-built reservoir, a $100,000 expense alone.

By 1873, when the hospital was supposed to be complete, it was nowhere near finished - and already $1.2 million over budget.

The public wasn't impressed. That year, The New York Times ran a scathing editorial about the hospital's spending.

The flooring was too fine, the heating system too large, the pipes oversized, the reservoir extravagant.

The construction team even blasted away a rock formation - spending $30,000 on the job - because they worried patients might escape, fall in, and be too hard to retrieve.

The newspaper's verdict was clear: the state had lost control of its own project.

And yet, the money kept flowing. The hospital remained under construction for 25 years, growing far beyond its original scope.

By the early 1900s, it was one of the largest asylums in the Northeast, with its own churches, a power plant, and a morgue.

The city of Poughkeepsie was changing, and so was the hospital's role in it.

Today, there are plenty of things to do in Poughkeepsie, New York, but in 1871, this was the main attraction: an institution built to house, treat, and, in many cases, hide away the mentally ill.

Hudson River State Hospital was a business venture as much as it was a place of healing.

It was an investment in a growing town, a statement of grandeur, and a real estate deal that had already rewritten the region's landscape.

The Rise of an Empire of Madness - Infrastructure, Expansions, and Daily Operations

By the early 1900s, Hudson River State Hospital had become a machine. The campus stretched across hundreds of acres, its roads lined with red-brick wards, towering smokestacks, and greenhouses.

Inside, it functioned like a factory of treatment - some patients walked freely across the grounds, others spent their days restrained, their names recorded in ledgers that kept track of thousands.

The asylum needed to expand. In 1952, the Clarence O. Cheney Building opened - a ten-story medical facility with offices, exam rooms, and psychiatric housing.

Its steel frame and brick exterior towered over the landscape, a reminder that the hospital was growing, adapting, taking in more patients than ever before.

The same decade saw the construction of a tuberculosis ward and a new refrigerating plant.

Cold storage was essential - this was a city within a city where food, medicine, and bodies had to be preserved.

At its peak, Hudson River State Hospital housed 6,000 patients. The staff worked shifts through its hallways, managing everything from hydrotherapy treatments to shock therapy sessions.

The daily routine was relentless - wake-up bells at dawn, meals served in giant halls, therapy sessions in rotation.

The hospital wasn't just treating the mentally ill; it was shaping the economy around it.

Local businesses supplied food, equipment, and medical supplies. Staff members bought homes nearby. The psychiatric industry was booming, and as long as patients kept coming, the hospital kept growing.

In 1971, a new addition was unveiled: the Herman B. Snow Rehabilitation Center.

This wasn't another medical ward - it was built for recreation. Two bowling lanes, a basketball court, an auditorium, even an indoor pool.

It was meant to feel normal, like something out of a suburban community center.

But the world outside was changing. Psychiatry was moving toward outpatient treatment. Drugs were replacing long-term institutionalization.

The hospital had spent over a century expanding - but soon, the era of sprawling asylums would be over.

The Slow Collapse - Market Shifts and Declining Demand

By the late 1970s, Hudson River State Hospital had become a shell of its former self.

The patient count had dropped to 1,780, and entire wings stood empty, their floors sagging under years of neglect.

The hospital had spent decades building itself up - now it had to figure out how to survive while shrinking.

The state tried to consolidate. In 1994, the hospital merged with the Hudson River Psychiatric Center, another facility in Dutchess County.

It was a cost-saving measure, part of a broader shift away from institutionalization.

Long-term stays were becoming rare. Instead of filling massive wards, patients were being treated in smaller outpatient centers.

The hospital, once a booming operation, was running out of people to serve.

Parts of the main building were abandoned. The grand patient wings, once built to house hundreds, were empty. In some areas, ceilings caved in, exposing wooden beams charred from a fire in the 1960s.

The state debated what to do next. The hospital still had its National Historic Landmark designation, but preservation and practicality didn't always align.

By 2003, the doors had closed for good. The last patients had been transferred out, and staff had left buildings that had been running for over a century.

There was no ceremony, no farewell. Just padlocks on the doors and empty halls left to the elements.

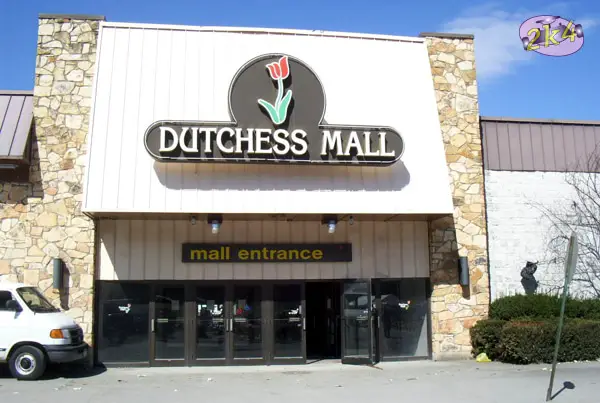

Outside, Route 9 filled with strip malls and new housing, the past buried under fresh pavement.

The hospital gates, once an entry to another world, now led nowhere. Inside the rusting fences, the asylum sat untouched - its halls empty, its future uncertain, its past refusing to fade.

Preservation Battles and Real Estate Deals - The Fight for Hudson River State Hospital

For years, the abandoned buildings sat behind fences, slowly falling apart.

The main administration building - the massive Kirkbride structure - still stood, its High Victorian Gothic towers cutting through the sky.

But the rest of the campus? It was crumbling. The walls peeled, windows shattered, entire sections of the roof gave way.

In 2005, the state sold 156 acres of the property to Hudson Heritage LLC, a subsidiary of the Chazen Companies, for $2.75 million.

The plan was ambitious: transform the old hospital grounds into a high-end development with apartments, retail spaces, and a hotel.

But before any construction could begin, the developers needed approval from the Town of Poughkeepsie.

That approval didn't come easily. In 2005, the town placed a moratorium on new construction, slowing down every major development project, including Hudson Heritage.

There were zoning issues, environmental reviews, and debates over historic preservation.

By the time the project started moving again, it was already 2007 - and then came the fire.

On May 31, 2007, lightning struck the hospital's south wing. The male housing ward, already weakened by years of decay, went up in flames.

More than a dozen fire companies rushed to the scene, but the damage was too much.

The entire section was lost. Restoration plans for that wing were abandoned, and preservationists worried the rest of the site would follow.

Despite the setbacks, developers kept pushing forward. In 2012, CPC Resources, a subsidiary of Community Preservation Corporation, took over ownership and put the land back on the market.

Walmart showed interest, looking to buy a portion of the property for a superstore.

But Poughkeepsie town officials resisted. No one wanted the hospital's history erased for a big-box retailer.

In November 2013, an undisclosed buyer stepped in. The sale went through, but no one knew exactly what would come next.

The only certainty was that Hudson River State Hospital's fate was now in private hands.

Demolition, Fire, and the Push for Redevelopment

For years, the hospital sat untouched, a magnet for trespassers, urban explorers, and vandals.

Security patrolled the grounds, but they couldn't stop everything. In April 2010, firefighters responded to two separate blazes, both suspected of arson.

Then, on April 27, 2018, another fire broke out - this time in the administration building.

It started in the early morning hours, flames climbing through the wing, lighting up the night sky.

By 2016, the first demolition crews arrived. The smaller buildings went first - the old dormitories, auxiliary structures, the morgue.

In 2019, Ryon Hall, the building once used to house violent and criminally insane patients, was torn down.

The next year, the Clarence O. Cheney Building followed, its ten-story frame reduced to rubble.

But the Kirkbride? That was different. The developers had agreed to preserve the administration building and repurpose it as part of the new Hudson Heritage project.

The idea was to keep the structure standing, even as everything around it changed.

Hudson Heritage took shape as a $300 million mixed-use development, blending residential units with commercial spaces.

Marist College, located nearby, eyed the area for student housing. Retailers lined up, looking to claim storefronts in the new shopping district.

Even a hotel was in the works, part of a larger vision to bring tourism dollars into Poughkeepsie.

By 2020, the northernmost tower of the hospital still stood, waiting for its next phase.

The Great Lawn - once a space for patients to roam - was slated for preservation, a nod to the hospital's past.

Everything else? It was either repurposed or erased, making way for what was coming next.

Hudson River State Hospital Now - Preservation or Erasure?

The wind cuts through the abandoned corridors of the Hudson River State Hospital, rattling loose window panes, sweeping past crumbling walls.

The Kirkbride building still stands - barely. Once the heart of a psychiatric empire, it's caught between preservationists fighting to save it and developers eager to build over its past.

It's February 2025, and Poughkeepsie's most infamous landmark remains in limbo.

The Hudson Heritage project - a $300 million development - is taking shape. It will turn the hospital's 156-acre grounds into a mix of retail stores, apartments, and a hotel.

But the main building? That's a problem. Fires in 2007 and 2018 left gaping holes in its structure, and the cost of restoring it keeps climbing.

The developers have promised to keep parts of the Kirkbride, but more and more disappear with each passing year.

Local preservationists argue that tearing it down would erase an irreplaceable piece of history.

But history alone won't pay for reconstruction, and the developers say too much damage has already been done.

The town of Poughkeepsie is caught in the middle. There's demand for new housing, for commercial space, for something other than a rotting asylum on the hill.

But there's also hesitation. The Kirkbride isn't just a building - it's a monument to the way mental health care changed over a century.

From overcrowded wards in the 1920s to deinstitutionalization in the 1990s, its walls tell a story that a shopping plaza won't replace.

For now, the decision hangs in the air like the dust inside its empty halls. Some parts of the hospital are gone forever - Ryon Hall, the Cheney Building, the morgue.

But Kirkbride still waits, its fate undecided, its history clashing with the future rising around it.