Where the Matinees Once Played

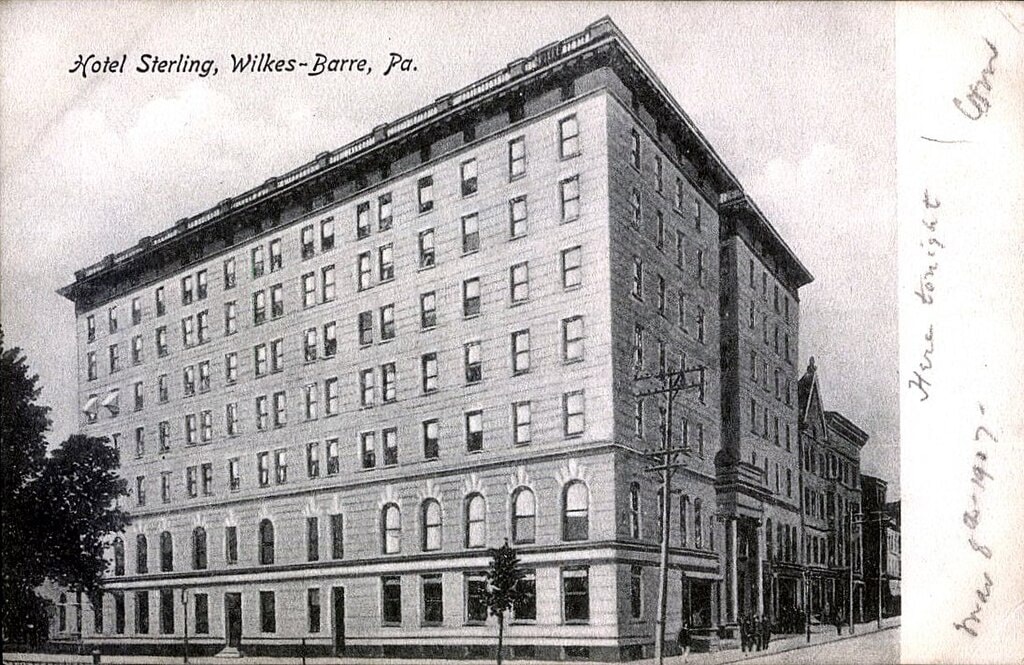

The corner of River and Market was never quiet. Even now, the lot stays open to the sky, but it once carried four stories of limestone, brick, and carved detail. The sound of wagons, then engines, passed beneath windows that looked out toward the levee, the rooftops of Wilkes-Barre crowding behind.

Before it was a hotel, the site was a music hall. By 1898, its name belonged to Emma Sterling, whose late husband, Walter, had held a stake in the hall. Her push brought about the new construction.

The hotel stood upright and squared, with something reserved about it, but its core function was hospitality. Not status. And not theater, though part of a painted sign reading "Matinees" still surfaced years later.

Building the Hotel Sterling, Brick by Brick

Plans began in 1897. The group behind it was local investors with ties to the performing arts. They had owned the music hall on the site.

At first, they called the project the Algonquin. That name disappeared quietly. The one that remained was Emma E. Sterling.

Her husband, Walter G. Sterling, had passed in 1889. He never saw the foundations poured.

The early design, drawn up by J.W. Hawkins, had a steep roofline, towers, and rows of dormers. It looked across the Atlantic for its style.

Local backers turned it down. The final design simplified those flourishes. A limestone facade took the front-facing sides, while the others stayed brick.

The construction was handled by W.H. Shepard & Sons.

The hotel opened on August 14, 1898. It held 175 rooms and 125 bathrooms, unusual for the time.

There's no full record of the exact layout, but the numbers suggest that many of the rooms were suites. W.A. Reist and Sylvanus Stokes managed the launch, leasing it for ten years.

From the start, the Hotel Sterling set the bar for things to do in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

Ownership Stakes and the Hotel Plaza Challenge

By 1920, control of the Hotel Sterling shifted. A local investor named Homer Mallow had become the primary stockholder and president of the company.

Under his direction, the name quietly evolved. People began calling it the Mallow-Sterling. The business was steady but not without pressure.

Three years later, a newcomer arrived just down the block.

In 1923, the Hotel Plaza opened on Market Street. It stood fourteen stories high, double the height of the Hotel Sterling. The New York firm Warren and Wetmore handled the design, giving the structure a more vertical profile and a newer aesthetic.

From the sidewalk, the contrast was hard to miss. The Sterling's older elegance now had a competitor that looked newer, taller, and styled for a different decade.

But the Hotel Plaza didn't last independently. By 1927, the Hotel Sterling acquired it outright. The deal expanded the property and set up new operational possibilities.

Now, the company controlled two buildings with different audiences, architectural tones, and floor counts.

That kind of consolidation gave the Sterling Hotel more visibility in Wilkes-Barre's hotel market. It helped it stay competitive in a city still benefiting from coal trade, freight rail, and a growing middle class.

Sordoni's Merger and the Sterling System Model

In 1936, Andrew Sordoni bought the combined Sterling and Plaza properties. He already had ties to construction and transportation, and this move folded hospitality into his portfolio.

He didn't just hold the property - he reorganized it. A four-story connecting structure went up between the original hotel and the Plaza Tower.

The connector unified the properties physically and operationally. Guests moved between them through a long, wide corridor known as Peacock Alley, named after the corridor in the Waldorf Astoria.

Sordoni's design avoided a showy renovation. Instead, it balanced the function with controlled detail. The new hallway gave the combined hotels a better layout for event hosting, internal flow, and room segmentation.

During this period, Sordoni also grouped this property with others he owned. The network became known as the Sterling Hotels System.

The name pointed to consistency and branding across multiple locations. This period, stretching from the late 1930s through the postwar years, marked the property's most cohesive phase.

It now operated across connected buildings, under single leadership, and with the infrastructure to support varied uses: conventions, short stays, long-term tenants, and banquet traffic from Wilkes-Barre's industrial firms.

Residential Shift and Market Drift in the Midcentury Years

After WWII, Wilkes-Barre's economy began to wear down. The coal industry, once central to the region's identity, declined quickly.

By 1959, the Knox Mine disaster pushed it past recovery. With that loss came ripple effects. Industries pulled out, job markets shrank, and the Hotel Sterling had to adapt.

During the 1960s and 70s, the hotel no longer held its old client base. Instead, the property split its use.

The original 1897 building was turned into apartment-style housing for retirees. Inside the Plaza Tower, students from King's College and Wilkes College rented rooms.

Those units were often converted. Pairs of standard rooms became "efficiencies," with the second bathroom retrofitted as a kitchen.

The connector building, which had once helped manage flow between hotels, shifted to short-term lodging. It was the last piece that still functions as a traditional hotel.

But traffic declined steadily. By the early 1980s, the student tenants left. The Hotel Sterling's ability to compete with newer lodging options had worn thin.

Wilkes-Barre had more modern properties, with better amenities and easier upkeep. As the area's population declined and economic activity slowed, the Hotel Sterling's role narrowed to shelter more than hospitality.

Utility Debt, Vacancy, and Physical Breakdown

By the late 1990s, the Hotel Sterling was no longer sustainable. In 1998, the building's owner failed to pay a $227,000 electric bill. Service stopped. With no tenants and no utilities, the property shut down. It never reopened for commercial use.

What followed was a decade of decay. In 2000, a small fire broke out, compounding the damage already caused by leaking roofs and winters that pushed water into walls, then froze and cracked them.

Vandalism accelerated the breakdown. Without heating or active security, the rooms, hallways, and infrastructure began to fail.

The hotel changed hands in 2002 through a tax sale. A nonprofit called CityVest took control and proposed a phased restoration. Their plan included demolishing the Plaza Tower and the connector structure.

That work moved forward in 2007. About $6 million in public funds backed the clearance, with support from federal, state, and county levels.

The idea was to reduce the footprint, clear space, and attract a developer who could work with the original 1897 building.

But the remaining structure was left exposed. No mothballing was done. Within a few years, the cost of restoration alone climbed to an estimated $35 million.

That did not include adjacent property development, which raised total projections to around $100 million.

Demolition Contracts and Timeline Gaps

In July 2011, after nearly a decade of vacancy and stalled plans, CityVest admitted the site had no interested developers.

With local support, they shifted their strategy. Luzerne County officials, after reviewing structural assessments, backed demolition.

That same year, Tropical Storm Lee pushed the Susquehanna River over its banks. The Hotel Sterling's basement flooded.

Once the water drained, several inches of silt remained. Engineers reviewed the structure and warned of collapse risk. The city rerouted traffic near the building.

By November 17, 2011, Wilkes-Barre's city council had voted unanimously to allocate $1 million for demolition.

The scheduled teardown in February 2012 never happened. Budget adjustments, permitting delays, and bid coordination caused setbacks.

Eventually, a contract was awarded to Brdaric Excavating on June 18, 2013. Their bid of $419,000 was the lowest of the 14 considered.

Demolition began on July 25, 2013. By July 30, the last piece of limestone was down.

Cleanup took another week, finishing around August 6. Crews stayed on to stabilize the foundation area. They had until September 23 to complete that work.

From start to finish, the demolition effort ran more than 17 months late, but by August 2013, the hotel was gone, leaving only grade and soil where three buildings once stood.

Property Vacant, Funding Pulled, Project Abandoned

In the years after demolition, the site stayed undeveloped. There were renderings, proposals, and press statements, but no new project broke ground. Public frustration followed.

In 2018, interest revived briefly. Developer Hysni Syla floated the idea of a new hotel build. Public funding was discussed. Luzerne County earmarked $3 million in potential support. But by May 2025, plans had changed.

Rather than build on the former Hotel Sterling lot, the developers shifted to 46 Public Square. The new plan focused on converting a vacant seven-story office building into a 110-room hotel with a gym, restaurant, and conference space.

The original Hotel Sterling parcel, once the city's most prominent address, was no longer part of the project. The site would be listed for sale again. County officials began the process of revoking the unused commitment.

A June 3, 2025, article in the Citizens Voice framed the question directly: What happens now to the old Hotel Sterling site?

No new answers followed. The lot remains inactive. Its past is clear. Its future, as of summer 2025, remains uncertain.

🍀