Brick by Brick, Justice Held Its Ground

The 1870 Old Lake County Courthouse in Lakeport, California, does not rely on its looks to explain why it matters.

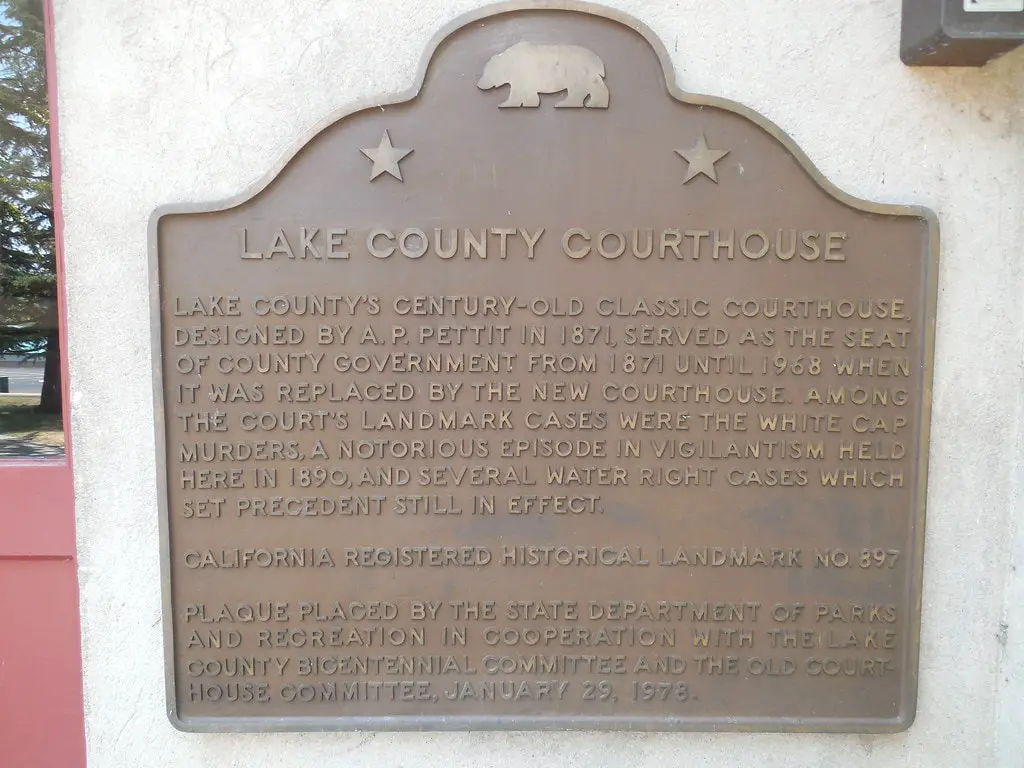

You can see its age in the masonry and guess the stories if you stand there long enough. Built in 1870, it sat through trials, upheaval, and one of California's worst earthquakes.

At 255 N Main Street, it still stands, surrounded by Courthouse Park, with more than enough history inside to count as one of the most steadying things to do in Lakeport, California.

Contracts, Fires, and County Seats

Lake County was created in 1861, drawn from parts of Mendocino and Napa counties.

Early civic development leaned toward Lakeport, though the first courthouse built there, a wooden structure, burned down in 1867.

That loss led to a brief relocation of the county seat to Lower Lake, where officials operated from a temporary building.

The county's records were moved, too, though they didn't stay long. The new site proved unpopular.

In 1870, A.P. Pettit, a contractor from San Francisco, was hired to construct a more permanent courthouse in Lakeport.

The contract went forward with brick construction as a central feature, a decision that proved lasting.

Construction ran into early 1871. The structure used local brick, a detail that connected it both physically and economically to the town.

By the summer of 1871, the courthouse was in use. That same year, the seat of government returned to Lakeport and remained there.

The building's functions expanded over time, with the county school's library installed in the basement.

The courthouse hosted legal proceedings ranging from property disputes to water rights.

In 1890, it became the venue for the trial involving the so-called White Cap group, an event tied to vigilantism that made headlines across the state.

These facts did not depend on nostalgia. They were just part of the courthouse's working life, which lasted until 1968.

Built to Withstand, Styled to Last

Construction finished in 1871. No ornament, no wasted space - just brick and concrete, pulled from nearby kilns and poured with intent.

A.P. Pettit gave Lakeport a courthouse that could do the job and stay standing.

The Italianate design nodded to style, but it was structure that mattered.

The second-floor balcony, iron-framed and plain, wasn't decorative.

It served the courtroom directly. Bailiffs stepped out to read proclamations or scan the street.

That kind of detail wasn't symbolic. It worked.

When the 1906 quake hit, buildings all over Northern California crumbled.

This one didn't. County records show no courtroom closures and no major structural failures.

Lakeport absorbed the jolt, but the Old Lake County Courthouse stayed in rotation.

It kept its footprint for nearly a century. Trials are above, records offices are nearby, and a school library is buried in the basement.

No expansions. No conversions. It didn't shift with the times - it held its ground.

In 1970, the National Register and the California Office of Historic Preservation both stamped it.

Official, finally, though the building had already done the work.

From Hearings to Holdings

The government left in 1968. Doors shut. For a while, no one knew what to do with the building.

It wasn't up to code, and it wasn't in demand. A few proposals leaned toward teardown. But the locals didn't let it drop.

By 1978, the place had been reclaimed as a museum.

Exhibits started small - geology, Pomo baskets, homesteader tools.

Nothing curated for effect. Just things that had been used, found, or saved.

One courtroom upstairs got restored, mapped to old plans, and rebuilt with quiet precision.

No costumes. No tours delivered on a mic. You walk in, and it looks like the court still runs there.

The research room holds registers, land plats, and newspaper microfilm.

It doesn't advertise. Appointments only. Some displays rotate based on loans or budget.

But core pieces - the ore samples, the woven baskets - have been there a long time.

Pomo Craft, State Funds, and the Quiet Power of Display

Inside the museum, one collection draws attention without having to try.

Eastern Pomo baskets - tight-weave, willow-stitched, feather-trimmed - fill cases across the first floor.

Most came from Big Valley and Elem communities. Some were traded locally decades ago.

Others came from estates or back closets - the oldest in the set likely predates 1890.

A replica tule boat sits nearby. It's about 14 feet long. Made from bundled reeds, sealed tight, and low to the waterline.

The original style was used across Clear Lake for fishing, moving families, and short crossings.

No attempt was made to dress it up. The point was to show how it worked.

In 2023, the state awarded Lake County a $75,000 grant through the California Cultural and Historical Endowment.

Two projects got greenlit: a new gallery space inside the Old Lake County Courthouse museum, focused entirely on Pomo material, and a life-size statue of a family group in bronze.

The sculpture is headed for the museum grounds in 2025.

The gallery expansion was developed in consultation with local tribal groups.

That detail mattered. Previous exhibits were built out using county artifacts.

This time, the intent was clearer. Display it, but don't strip it of context.

Unlike other parts of the museum, this wing won't rotate.

The materials stay. The wall text was reviewed, and the sourcing was documented.

The purpose wasn't to update the museum's look - it was to ground it more deeply in the region it describes.

Events, Hours, and the Work of Staying Relevant

The museum doesn't run like a civic monument. It runs on schedules, staffing, and what Lake County's budget can stretch to cover.

Its hours: Wednesday through Saturday, 10 to 4; Sundays, noon to 4.

Closed Mondays and Tuesdays.

Inside, some exhibits stay anchored - baskets, minerals, the restored courtroom.

Others rotate.

In 2018, they put up "Crime and Punishment in Lake County," a display that ran for several months and focused on 19th-century law enforcement methods, jail books, and original handcuffs.

They didn't advertise heavily. Visitors found it anyway.

Special events are irregular. When they happen, they're practical - guided tours, student visits, occasional evening lectures.

No theatrical overlay. The museum staff handles programming, depending on what's possible each year.

The location helps.

Right in downtown Lakeport, the Old Lake County Courthouse sits inside Courthouse Park, a flat rectangle of grass and old trees bordered by 2nd and 3rd Streets.

On warm days, people sit outside or pass through on their way to Main.

The setting's quiet, but visible.

The museum functions, but only because it's been worked on. Nothing here costs.

🍀