Westroads and the Promise of 1955

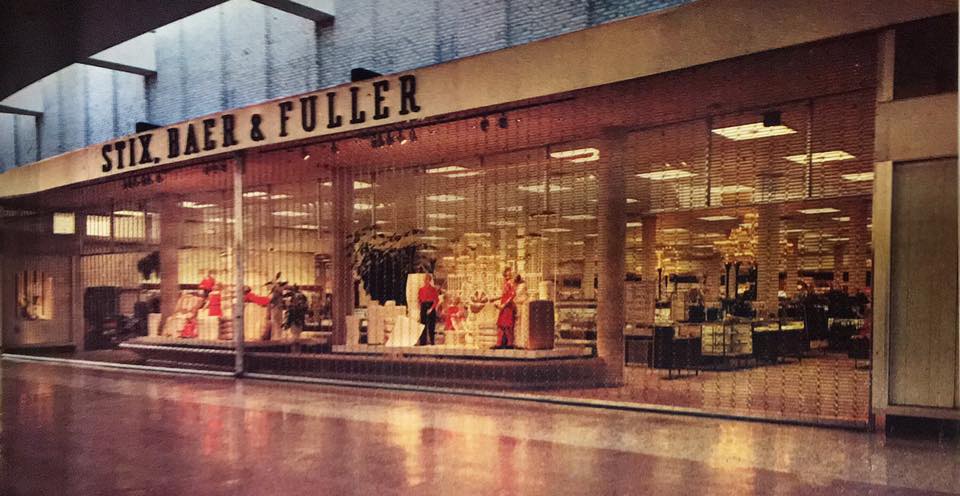

Before the era of climate-controlled promenades and food courts, there was Westroads Shopping Center. In 1955, at the intersection of Clayton Road and Brentwood Boulevard, Stix, Baer & Fuller planted its first suburban flag.

The department store, a four-story block of ambition, anchored a tidy strip of retailers that stared across a wide parking lot at the oncoming tide of the automobile age.

Richmond Heights widened its roads in anticipation. The store's restaurant, the Garden Room, served Encore Salad and alligator rolls under a glass wall overlooking Clayton Road.

Designed by the Bank Building & Equipment Corporation of America, the structure stood out for its geometry. Its pavilion-like facade jutted forward, hinting at modernity without quite letting go of formality.

The same concept would later echo in other St. Louis shopping experiments, River Roads, Crestwood Mall, each built with optimism that suburban expansion could be both orderly and grand.

Westroads became a place where shoppers tried on progress. And for three decades, that was enough.

From Westroads to Galleria: The 1980s Reinvention

Hycel Properties acquired the aging Westroads Shopping Center in 1984 with plans for a complete overhaul. The company intended to replace the deteriorating open-air strip with a modern enclosed mall.

Most of the original center was demolished, leaving only the north wing of the Stix, Baer & Fuller store and a few remaining tenants, including Walgreens.

John Graham & Co., a firm known for its work on large-scale shopping centers, was hired to design the new project.

The plan featured an enclosed retail concourse, glass atriums, and an internal service corridor running south to north for deliveries.

Dillard's, which had purchased the Stix chain that same year, expanded into the retained section of the original building.

Construction moved quickly, and by April 1986, Saint Louis Galleria opened with new storefronts, bright signage, and central air.

The project marked the site's full transformation from suburban strip center to regional shopping destination.

In May, Galleria 6 Cinemas opened above the food court, completing the reinvention of the property. Shoppers could now browse, dine, and see a movie without ever stepping outside.

The 1991 Expansion: A City of Retail

If the 1980s marked rebirth, 1991 was the moment of empire. Saint Louis Galleria doubled its footprint at a cost of $215 million.

Entire blocks of Richmond Heights disappeared: 99 homes, 20 small businesses, and the Junior League's three-acre plot were absorbed into the project. The mall now sprawled over 56 acres and 1.18 million square feet.

Two new anchors arrived to consecrate the expansion. Famous-Barr relocated its Clayton store into a vast 265,000-square-foot box.

Lord & Taylor took the southern flank, 115,000 square feet of marble and perfume. The grand opening, in August 1991, drew crowds that filled Brentwood Boulevard like a parade.

The mall's utility systems became as complex as its commerce. Engineers built redundant electrical feeds from four points and even an emergency generator that could keep lights flickering during outages.

For Richmond Heights, Saint Louis Galleria became both a lifeline and an identity. The city's revenue would soon depend on its tills.

The Boom Years: Retail Theater and New Icons

By the late 1990s, Saint Louis Galleria had hit its cultural stride. On an October Sunday in 1997, a new kind of store opened near the escalators: Build-A-Bear Workshop.

Customers could choose, stuff, and personalize teddy bears under fluorescent light. The idea, born at Saint Louis Galleria, would soon spread worldwide, turning the mall's corridors into retail folklore.

Apple arrived next, bringing a miniature version of its glass-and-aluminum temple. Urban Outfitters followed, adding bohemian contrast to the polished corridors.

The Cheesecake Factory opened in 2002, the first in the St. Louis region, where diners waited under chandeliers for slices the size of textbooks.

General Growth Properties bought the mall in 2003 for $235 million. Ownership shifted, but the momentum remained.

The Galleria had become the stage where new brands debuted and St. Louis shoppers rehearsed consumer trends before they went national.

Turbulence: Trains, Teens, and Recession

In 2006, the MetroLink station opened across from Saint Louis Galleria.

It made it easy for people to get there from downtown, and that turned out to be a mixed blessing. More crowds meant more problems. Shoplifting went up.

Fights started happening more often. By the next spring, the mall had a rule: anyone under sixteen had to come with an adult after 3 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays.

Then the recession hit. Jimmy'z shut down. Mark Shale closed. The city lost close to a million dollars in sales tax in one year. The Mark Shale space turned into restaurants and a comedy club, but none of them stuck.

Lord&Taylor's big store still sat at the end of the mall. Nordstrom was supposed to take it over and bring new life to the place.

The plans stalled when the economy tanked. Construction stopped for months. The store finally opened in September 2011, and everyone was just glad something finally did.

A Decade of Unease

The 2010s brought less expansion and more introspection. The Galleria's success, once measured in square footage, now depended on stability.

Protests over the 2017 acquittal of Jason Stockley disrupted the mall for days. Demonstrators filled the atrium, chanting for justice; police made twenty-two arrests.

Saint Louis Galleria closed early more than once that week. Violence, though rare, stuck in public memory. In 2018, a shopper stabbed another in an argument.

Two years later, a shooting left one man dead. These incidents, magnified online, chipped at the mall's image as a neutral suburban refuge.

At the same time, the business of shopping itself changed. Online retail grew. Foot traffic shrank.

Brookfield Properties acquired General Growth in 2018, inheriting both the mall and its anxieties. The new owner's challenge was not expansion but endurance.

The Present: Survival Through Adaptation

By 2024, the Saint Louis Galleria was still standing strong, though it didn't draw the same crowds it once did.

The big stores were Dillard's, Macy's, and Nordstrom. In June 2025, Nordstrom said it would shut down in August, blaming changing shopping trends.

The closing meant 135 people would lose their jobs, and left a huge 143,000-square-foot empty space right in the middle of the mall.

The same year, Saint Louis Galleria tried to reframe its identity. New tenants appeared: JD Sports, Luxmen, Savage Fenty, Miniso, and a relocated Barnes & Noble, which opened in October 2024.

The mix tilted younger, more eclectic. Experiential retail became the new mantra.

Then came the answer to the Nordstrom question: Dick's House of Sport. The announcement promised climbing walls, batting cages, and golf simulators, a nod to the idea that activity might succeed where aspiration failed.

It was less about luxury and more about movement, an evolution from shopping as display to shopping as sport.

Meanwhile, Brookfield put 5.6 acres of parking up for sale, a strip near Interstate 64 where the Cirque Italia Water Circus had performed the previous summer.

What Saint Louis Galleria Means Now

Saint Louis Galleria has stood in Richmond Heights for seventy years. It began as a strip mall, turned into an indoor shopping hub, and has kept reinventing itself ever since.

Every new owner tried to bring it up to date, layering fresh ideas on top of what was already there.

The city still relies on the mall's tax income. Families still meet under the skylights. Teenagers still drift through the food court in slow circles.

The Galleria no longer feels like a monument to luxury. It's more of a test site to see how long a mall can last.

If Dick's House of Sport finds its audience, the place could feel alive again. If it doesn't, the Galleria will be another mall that confused size for staying power.

For now, the lights stay on, the escalators run, and the smell of pretzels hangs in the air. The building keeps doing what it's always done: reflecting suburban life back at itself.