Breaking Ground on the South County Center Retail Model

The dome was the first thing you saw. Rising above the roofline, it capped the original Famous-Barr like a lid on a steel pot.

On opening day - October 17, 1963 - shoppers moved through wide, tiled walkways past display windows filled with gloves, handbags, and boxed sets of cologne.

The Rain Curtain Fountain stood near the center court, misting gently over the terrazzo floor.

South County Center opened in the St. Louis, Missouri suburb of Mehlville, at the junction of Interstate 55, Interstate 255, and U.S. Route 50.

It was a calculated location - accessible by highway, far enough from downtown, with room for parking.

Victor Gruen, the Austrian-born architect who helped invent the American mall, designed the layout.

May Centers funded the project, which brought in chains like Baker's Shoes, National Supermarkets, and Pope's Cafeteria.

The National Supermarket was on the basement level. By 10 am, carts were rolling past waxed produce and paper-wrapped meat.

It closed in 1973, but early on, it served as one of the anchors alongside Famous-Barr and JCPenney.

The JCPenney store didn't open until 1967 - four years after the South County Center debuted - but once it did, it helped round out the triad that defined the space for decades.

Famous-Barr was a prestige name. It drew families from Oakville, Lemay, and South St. Louis, especially during holidays.

Their window displays lit up in December. Back then, going to the mall was part of things to do in St. Louis, Missouri - you grabbed dinner, maybe watched a movie, and picked up linens on sale.

Even in the early years, retail wasn't the only draw. South County Center had climate control, public restrooms, and music piped through speakers.

By the end of 1963, it wasn't just a place to shop - it was where people lingered.

Retail Growth and Real Estate Additions

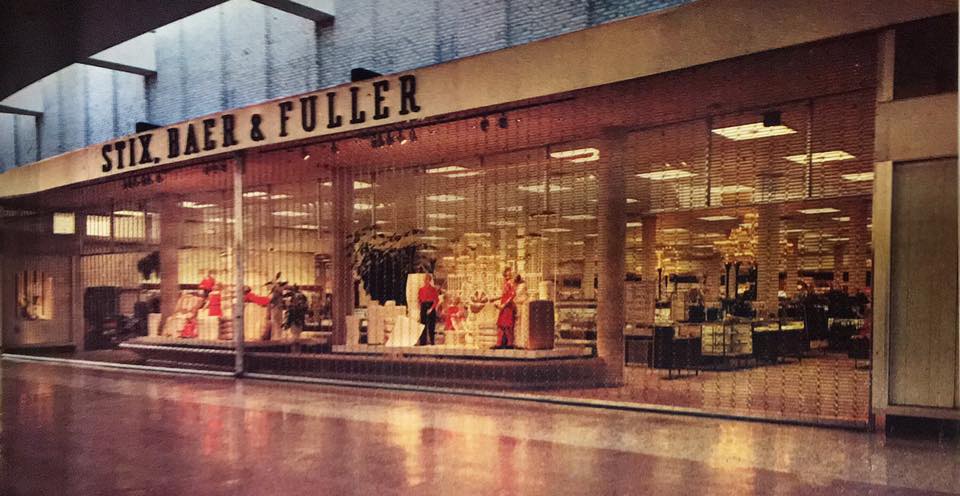

In 1979, a new wing opened on the south side. Anchored by Stix, Baer & Fuller, the extension added dozens of storefronts and an updated layout - wide corridors, neutral tile, and glass-walled displays.

Dillard's took over Stix in 1984. It didn't change much right away - same escalators, same ground-floor fragrance wall - but the name on the awning was different, and over time, the inventory leaned toward national brands.

In 1990, the Westfield Group bought South County Center. Based in Australia, the Westfield Group is known for large-scale shopping centers, and this one fits the model.

Over the next decade, Westfield invested in signage, lighting, and minor upgrades - nothing flashy, but enough to keep it moving.

Then came the early 2000s. In 2001, Sears opened on the west end in a newly built three-story structure.

That expansion added a two-level wing and a 12-bay food court. Chains like Sbarro, Panda Express, and Charley's Grilled Subs moved in.

It changed the traffic flow. People now parked near Sears and entered from the lot facing Lindbergh Boulevard.

Before long, smaller stores started rotating in and out - Express, KB Toys, Limited Too.

Leasing patterns shifted toward fast fashion and niche retail. The mall peaked in square footage and daily traffic during these years. Footfall was steady. Holiday weekends meant extended hours.

By the mid-2000s, South County Center had roughly 1 million square feet of leasable space and a full roster of tenants.

It was on every leasing agent's radar in the St. Louis, Missouri metro area.

Tenant Turnover and Anchor Retreats

In 2004, management tried something new: stores and restaurants with entrances facing the parking lot.

Qdoba opened first, followed by Applebee's, Noodles & Company, and Borders. You could eat dinner without ever stepping into the South County Center. For a while, that worked.

By 2007, Westfield let mall go. CBL & Associates Properties, Inc., based in Chattanooga, picked up South County Center along with three other Westfield malls in the St. Louis market.

The deal was part of a broader push to expand their regional portfolio.

Nothing changed overnight. The lights stayed on, the food court stayed full, and the banners still hung from the ceilings. But from that point on, CBL controlled the leases, the maintenance, the future.

Borders was along the west exterior wall near the food court until 2011. When it closed, Vintage Stock moved in the next year and sold used games, movies, and comics.

Applebee's closed in 2015. By 2016, DXL, a men's apparel chain, had opened in the space. The exterior signage changed, and the patio seating came down.

Noodles & Company ran from 2004 to 2023. The sign stayed up for a few months after the shutdown, then came down with little fanfare.

Qdoba is still there, still serving burritos and queso to lunchtime regulars.

Sears closed in September 2018. The three-level building - with escalators and service elevators - has been empty since.

In 2019, Round One Entertainment, a Japanese bowling and arcade chain, announced plans to take over the space. By January 2021, the deal was off.

No new anchor moved in, and the west wing started thinning out. A few smaller stores stayed, but others - Champs, Aeropostale, and even Bath & Body Works - cut hours or left entirely.

Inside the mall, empty storefronts appeared behind blacked-out glass. Some had "For Lease" signs taped inside.

Others were stripped bare - no carpet, no lights. Leasing slowed, especially after 2020. National chains pulled back.

Local vendors couldn't cover square footage costs. The mall stopped expanding. It began adjusting instead - downsizing, consolidating, waiting.

Anchor Losses and Retail Retreats

On January 9, 2025, Macy's announced its South County Center store would close. It was one of 66 locations the company planned to shut down nationwide.

A "Store Closing" sign went up within days - big red letters taped behind the glass.

By the second week of February, employees were folding sweaters into cardboard boxes.

Mannequins disappeared from the front windows. Clearance racks lined the aisles where spring displays used to be. First, the markdowns read 20%. Then 40%.

There was no final sale event. No music. Just hangers clicking, a few customers checking price tags, and the smell of perfume still faint near the old makeup counters.

The Macy's space opened in 2006, replacing the original Famous-Barr. Before that, it was one of the mall's central draws - familiar to shoppers who remembered perfume counters and Black Friday crowds.

But Macy's is leaving in March.

By mid-February, the shelves started thinning. Luggage was on clearance, and leftover coats were discarded.

A few racks still stood near the old fragrance counters, but most were wheeled to the front for final markdowns.

Lacefield Music, a smaller tenant near the outer edge, was getting ready to shut its doors, too.

They'd been in the building since 1994. By the last week of February, the grand pianos were tagged with discounts, and handwritten signs listed the final sale: February 28. Their Chesterfield store would stay open.

On November 14, 2024, there had been another kind of headline. A man tried to steal merchandise from a sporting goods store inside the mall.

When police moved in, he fought back - resisting arrest and injuring an officer. Charges were filed.

The Sears building on the west end remains empty. V-Stock still operates near where Borders used to be.

Most customers walk in from the parking lot, browse DVDs or Pokémon cards, then leave without circling the mall.

Dillard's and JCPenney are the only two anchor stores still operating. JCPenney, which opened in 1967, remains in its original footprint.

Dillard's took over the Stix, Baer & Fuller spot in 1984 and hasn't moved since. Their doors are open. But foot traffic varies.

The food court looks the same - twelve bays, plastic chairs, skylights overhead. But some counters are dark, and the smell of fresh food doesn't linger like it used to.

On a weekday afternoon, the parking lot isn't empty, but there's space. Inside, a few walkers move past shuttered stores and closed gates. Music plays overhead. There are still lights in the food court.

Too long.

Thanks for calling that out. Not every reader wants a deep dive. Some want the feeling, not the whole timeline.

food court has wooden chairs not plastic

It's funny how small things tell a story. Wooden chairs instead of plastic suggest someone once cared about comfort and style. About staying awhile.

"In 1973, a new wing opened on the south side. Anchored by Stix, Baer & Fuller, the extension added dozens of storefronts and an updated layout—wide corridors, neutral tile, and glass-walled displays."

It was the fall of 1979 when the new wing with Stix, Baer & Fuller opened.

You're right to point that out. Fixed now.

Thank you, loved the trip down memory lane

Glad it brought back those memories. Thanks for reading and sharing your reaction.