The Business of Building Wickham House

In the early 1800s, Richmond was a city on the move. The economy was growing, fortunes were being made, and the wealthiest residents were shaping a new kind of high society.

Grand homes began to rise in the Court End district - brick, symmetrical, elegant - designed to announce success before anyone even stepped through the door.

One of the most ambitious belonged to John Wickham, a man who understood better than most how power worked in America.

By 1812, Wickham had already cemented his reputation. He was a skilled lawyer, a sharp strategist, and someone who knew how to navigate both the courtroom and the dining rooms of the city's elite.

His name had been in the national papers just a few years earlier when he defended former Vice President Aaron Burr against charges of treason.

The trial, held in Richmond, was the spectacle of the decade - federal prosecutors called for Burr's execution while Wickham built a defense that helped him walk free.

The trial was a national scandal, with Thomas Jefferson personally pushing for Burr's conviction.

Wickham helped secure Burr's acquittal, which led to accusations that he was siding with a traitor.

At the time, defending Burr was seen as a morally questionable choice, especially in Richmond's legal circles.

The case added to Wickham's fame but also tied his name to one of the most controversial trials in American history.

That same year, he commissioned a house that would match his standing. He hired architect Alexander Parris, a rising talent from Massachusetts who would later go on to design Boston's Quincy Market.

Some say Robert Mills or Benjamin Latrobe had a hand in the design, but the records credit Parris.

At the time, Court End was where the city's wealthiest residents built their homes, drawn to its proximity to the Virginia State Capitol.

Land values were high. The right address mattered. Wickham knew that in a city where influence was currency, the house itself would be part of his legacy.

Architectural Design and Interior Market Appeal

The Wickham House was built to make an impression. From the street, its symmetrical facade gave off an air of order and restraint - stuccoed brick, a shallow hip roof, and paired columns framing the entrance.

But step inside, and the house told a different story. The wealth was on full display.

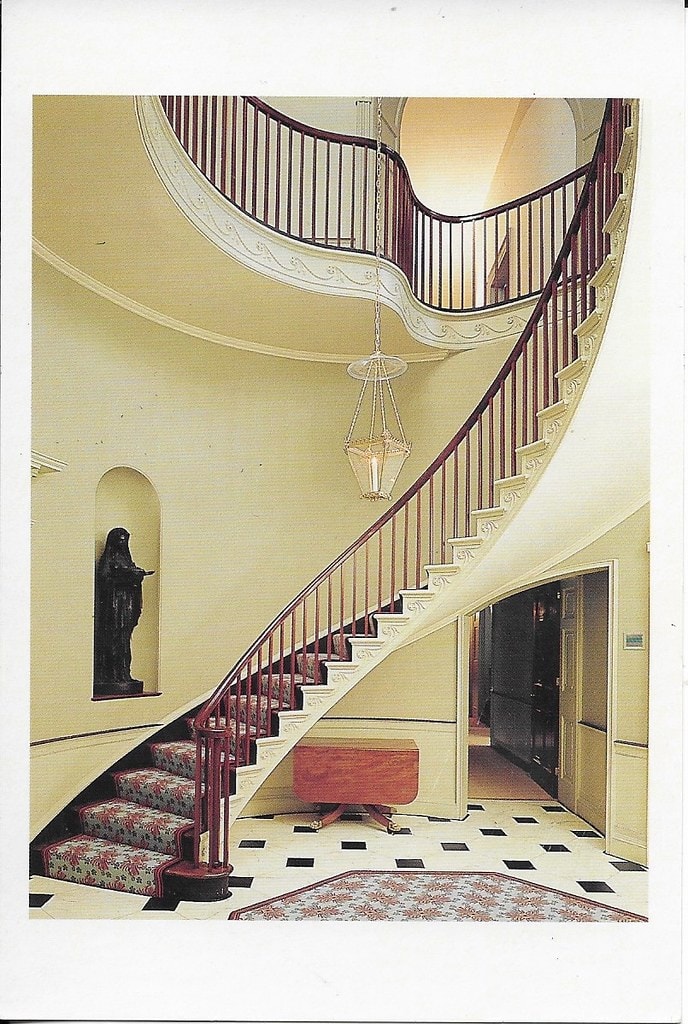

A staircase unlike any other in Richmond curved through the center of the home, sweeping upward in one fluid motion.

It was elliptical, designed to guide the eye and impress guests before they even reached the second floor.

The walls were covered in neoclassical murals, painted directly onto the plaster - Greek gods, Roman columns, Egyptian motifs, and a gallery of power drawn from the ancient world.

John Wickham had spared no expense. The windows, divided into three sections, let in soft, filtered light that reflected off imported wallpapers and elaborate moldings.

Every detail was designed to show status. Even the doors - solid, heavy, carefully carved - were meant to send a message.

This was a house built for entertaining, hosting judges and politicians, and reinforcing Wickham's place in Richmond's elite.

By the mid-1800s, tastes had changed. The next owner, John Ballard, redecorated. The Federal style gave way to Victorian opulence - plush fabrics, ornate furniture, and deeper colors.

The rooms, once crisp and symmetrical, became softer and more elaborate.

Outside, the original gardens stretched across nearly a full city block, with symmetrical paths and carefully trimmed hedges.

By the 20th century, much of that land was gone, swallowed up by development, leaving behind only a small courtyard.

But inside, the house remained intact, its murals and staircase untouched by time.

Richmond grew, styles changed, but the Wickham House stayed frozen in the world it was built for - an era where architecture was used to announce power, and wealth was measured in square footage and imported design.

Changing Ownership and Shifts in Property Use

By the 1880s, Richmond was no longer the city John Wickham had known.

The Civil War had reshaped everything - fortunes were lost, entire neighborhoods changed hands, and once-grand homes in Court End were falling into disrepair.

The Wickham House, built as a statement of wealth and influence, was no longer just a private home. It was about to become something else.

In 1882, the house was sold to Mann Valentine II, a businessman whose fortune came from a tonic called Valentine's Meat Juice - a concentrated beef extract he claimed could restore health to the sick.

The product had made him rich, and with that wealth, he started collecting. He amassed artifacts from around the world, including items taken from Native American burial sites.

The Wickham House became more than a residence; it became the centerpiece of his growing collection.

Valentine had bigger plans. By the time of his death in 1892, he had set things in motion for the house to be turned into a museum.

His collection, which included everything from Civil War relics to items from ancient civilizations, was donated to the city.

In 1898, the house officially reopened as The Valentine Museum, making it one of Richmond's earliest institutions dedicated to history.

Over the next several decades, the museum expanded. The organization bought adjacent row houses, turning them into exhibit spaces and administrative offices.

Restoration efforts started early - preservationists stripped away layers of Victorian-era updates, working to bring the house back to how it had looked in Wickham's time.

Some rooms were carefully reconstructed using period records, while others were left as they had evolved, showing the layers of history that had passed through the house.

By the 20th century, Wickham House was no longer just a home or even a museum. It was part of a larger effort to preserve Richmond's past, a place where the city's changing history was written into the walls.

Public Access and the Business of Historic Preservation

By the 20th century, the Wickham House was no longer just an old mansion - it was an attraction.

Richmond had started marketing its past, turning its historic districts into places people could visit.

The Valentine Museum, now in charge of the house, saw the opportunity.

The museum's model was simple: open the doors, let the public in, and make history an experience.

In the 1960s, when interest in historic preservation grew, funding started to follow.

The National Park Service designated the Wickham House a National Historic Landmark in 1971, a label that came with both recognition and resources.

Tourism helped keep the house running. Richmond had already established itself as a destination for Civil War history.

However, the Wickham House offered something different - a look at life before the war, at the people who shaped the city in its early days.

School groups came to learn about Federal-era architecture. Historians studied the murals and design.

Visitors walked through the rooms where politicians once sat, surrounded by imported wallpaper and heavy, carved furniture.

To keep up with the times, The Valentine expanded its programming.

New research projects looked deeper into the lives of the enslaved people who worked in the house, shifting the focus from just the wealthy owners to the full picture of who lived there.

Exhibits were updated. Private events brought in funding. Preservation efforts became an ongoing business, requiring grants, partnerships, and constant upkeep.

At the same time, real estate and tourism in Richmond's Court End continued to evolve.

The district, once packed with similar homes, had changed. Some of the old mansions had been demolished or converted into offices. But the Wickham House remained, holding on as the city grew around it.

Planning a Visit and Exploring Richmond's Historic Market

The Wickham House isn't the kind of place you stumble across by accident.

Tucked into Richmond's Court End district, just a few blocks from the Virginia State Capitol, it sits behind iron gates, its pale stucco facade blending into the quiet row of historic buildings.

But for those who know where to look, it's a time capsule - one of the best-preserved glimpses into early 19th-century life in the city.

For those looking for things to do in Richmond, Virginia, the Wickham House offers a different kind of history.

It isn't Civil War battlefields or Confederate memorials - it's the world that existed before all that.

The city as it was when ambitious lawyers, merchants, and politicians were carving out their place in the young nation.

The Court End neighborhood, once the most sought-after address in Richmond, still holds onto pieces of that world.

A short walk away, you'll find the John Marshall House, where the Chief Justice lived.

A few blocks down, the Museum of the Confederacy and St. John's Church, where Patrick Henry gave his famous speech.

The Wickham House isn't the biggest historic attraction in the city, but it has something others don't - an intimacy.

The wallpaper, the furniture, the light slanting through the tall windows - everything feels lived in as if the past never fully left.

It's a reminder that Richmond has always been a city of power, ambition, and reinvention. The buildings may stay the same, but the stories keep unfolding.