Back When a Mall Meant More

In 1972, Grand Central Mall opened its doors in Vienna, a suburb of Parkersburg, West Virginia, with more than retail in mind. The place wasn't just big - it reshaped local shopping for anyone within thirty-five miles.

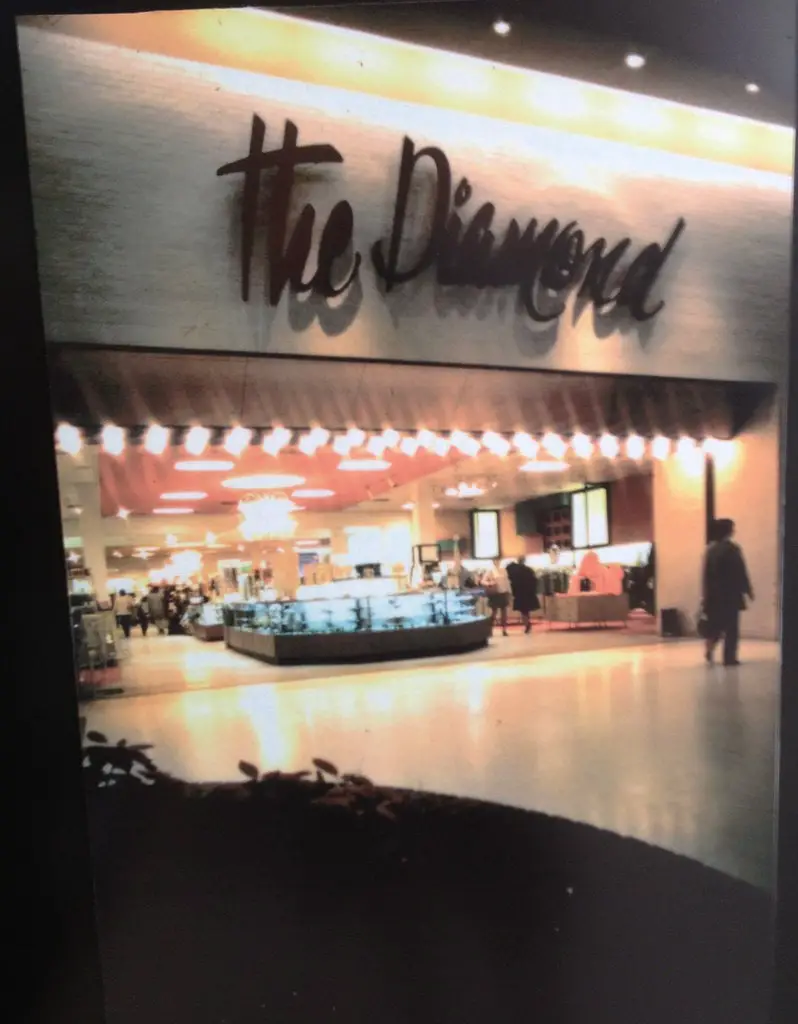

Anchored by names like The Diamond, JCPenney, Sears, and G.C. Murphy, it gave the Mid-Ohio Valley something it hadn't had before: an indoor, all-season center for buying shoes, grabbing lunch, and walking a few laps.

It's easy now to overlook what that meant at the time. Strip plazas and box stores hadn't yet diluted the idea. For many in the region, it was the start of their own list of things to do in Parkersburg, West Virginia.

Anchors, Acreage, and 1970s Retail Strategy

Grand Central Mall didn't arrive by accident.

Developer Eugene Lebowitz opened it in 1972 during a wave of indoor mall construction across small cities.

At more than 900,000 square feet, the layout pulled together four major anchors: JCPenney, Sears, G.C. Murphy, and The Diamond. Each one carried regional weight.

The Diamond, then part of Associated Dry Goods, gave the mall a department-store presence that felt upscale to many shoppers.

By combining anchor tenants with dozens of inline stores, the design borrowed from larger metro models but scaled to fit a regional base.

There wasn't another enclosed mall nearby. That mattered.

Its early layout also reflected a common strategy from that era: bring people inside and keep them there.

The single-level plan made it easy to navigate. Its early floor plan concentrated foot traffic toward central courts and key intersections.

A dime store on one end and two full-line department stores at opposite corners helped balance circulation.

Even without full public transit connections, it drew regular traffic from across Wood County and beyond.

Storefront Swaps and Portfolio Shifts (1983-2008)

The first wave of tenant turnover began early. In 1983, The Diamond closed its Grand Central Mall location.

The space didn't sit empty for long. It was reworked into Stone & Thomas, a regional chain with roots in Wheeling.

That conversion, coming just over a decade after opening, marked the start of a pattern: one name out, another brand in, often with only minor physical changes.

Stone & Thomas ran until 1998 when its parent company was absorbed into the Elder-Beerman chain.

Phar-Mor, a discount pharmacy, was also added somewhere along the way but didn't last beyond 2002.

That storefront later became home to Steve & Barry's, a national clothing retailer aimed at college students and families.

Ownership shifted, too. Glimcher Realty Trust acquired the mall in 1993 and started pumping money into upgrades by 1996.

That $8 million expansion brought a new food court and a Regal movie theater.

The same year, Glimcher added a Proffitt's store, the first in West Virginia, as part of a two-mall push that also reached Morgantown.

That space would later be rebranded as Belk. Steve & Barry's closed in September 2008.

Its space now holds Dunham's Sports, which took over during the post-recession scramble for reliable anchor tenants.

Chain Closures and Outlot Rebuilds (2002-2019)

While the main concourse shifted slowly, the outlots changed faster.

In November 2002, four new names opened outside the mall walls: Toys R Us, Olive Garden, Long John Silver's, and Outback Steakhouse.

Each one extended the property's draw without requiring shoppers to step inside the main building.

Those names didn't all last. By 2016, Long John Silver's had closed, and Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen took its space.

Three years later, in 2019, Big Lots moved into the old Toys R Us footprint.

These swaps reflected national closures and consolidations, not just local choices.

Still, Grand Central Mall adapted to them without losing control of its square footage.

The Elder-Beerman department store, formerly Stone & Thomas, closed at the end of January 2018.

That wasn't a surprise after its November 2017 announcement.

What came next was more interesting: twenty thousand square feet from the old store was turned into an H&M - the first one in West Virginia.

Sears lasted a little longer. It held on until December 2018, when it was shut down as part of a national round of twelve store closures.

That created a major vacancy, but the reshuffling of that space came later, in 2021.

No anchors were added in the interim.

Redevelopment of Anchor Square Footage (2021)

The vacant Sears space didn't stay empty forever, but the rebuild took time.

By early 2021, Grand Central Mall had a new layout plan ready.

Four major national retailers moved in that year, all split across the old anchor footprint.

TJ Maxx and HomeGoods opened on March 11, followed by PetSmart on March 27.

Ross Dress for Less joined a few months later, on July 16.

None of these were firsts for West Virginia, but their combined arrival filled a chunk of dormant real estate.

Instead of replacing Sears with a single department store, management chose to divide the square footage among discount and specialty retail.

That realignment matched national leasing trends but also reflected the available tenant pool.

It allowed the mall to stay filled without betting on one brand to carry traffic.

Each store brought its own footprint and sales model.

TJ Maxx and HomeGoods leaned on off-price housewares and fashion.

PetSmart, with its own entrance, added animal supplies and grooming services.

Ross landed last but helped round out a broader category mix.

None of them backfilled the exact role Sears had played, but together, they helped stabilize the outer anchor wing by mid-2021.

Outlet Conversions and National Leasing (2023-2025)

The tenant mix continued shifting after 2021, and by 2023, changes reached the top-line branding.

On June 17 of that year, the full-line Belk store officially transitioned into a Belk Outlet.

That swap followed corporate strategy more than local pressure, but the message was clear.

The space was staying open, though in a modified format.

The mall pulled in new tenants throughout 2024.

Rally House, a 6,000-square-foot regional sports apparel store, opened next to IronHeadz Sports Nutrition in March.

Around July, both MINISO and Pandora launched new locations, anchoring one stretch of the internal corridor with retail aimed at younger shoppers.

FYE joined them in September with a 5,000-square-foot setup dedicated to pop culture and niche media.

Blacc Angel Body Care Company opened in October 2024 near GR8R Gaming.

Its product mix is centered around natural skincare and personal grooming and is aimed at local shoppers looking for smaller-scale items.

Management is now under Washington Prime Group. More than 200,000 square feet of new or remodeled space had been completed across several years.

As of early 2025, Grand Central Mall had about 80 stores and restaurants in operation.

The approach leaned toward volume, category balance, and continuous backfilling.

Events Programming and Property Foot Traffic (2024-2025)

Retail wasn't the only draw for Grand Central Mall in 2024 and 2025.

A steady rotation of events filled its calendar, aimed less at flash and more at consistency.

In March 2025, the West Virginia Racing Heritage Festival held a stock car show inside the property.

Vintage racers, some with local track history, were displayed alongside photos, stats, and memorabilia.

It wasn't a massive event by metro standards, but it pulled steady traffic through the mall's central corridor.

Seasonal programming leaned into tradition.

"Photos and Visits with Bunny" ran from March 21 through April 19, offering appointment slots across four weekends.

A one-day "Sensitive Bunny" event took place on April 6, adjusted for lower noise and smaller crowds.

These weren't new concepts, but the repetition seemed to matter more than novelty.

Vendor fairs and craft shows returned to the 2025 calendar in fixed seasonal blocks.

Three-day shows were scheduled in May, September, November, and December.

All were hosted inside the mall's event spaces, with local artisans setting up booths among national chain stores.

These events gave smaller brands short-term access to foot traffic without requiring long-term leases, which also helped diversify the weekend mix without disrupting anchor traffic patterns.

🍀

If they want to attract people and have them stay there they should bring back the decor design they had in the 80’s. The ponds, the foliage, the lighting…….it was a very warm and inviting place to be. A place to just hang out and window shop. Now it is cold, bland and boring. I look forward to going to the mall from time to time but after a few minutes of being there I wonder why I did.

The phrase you used, "warm and inviting," sticks. Many malls today are technically updated but emotionally empty. That's not just nostalgia - it's architecture that mattered.