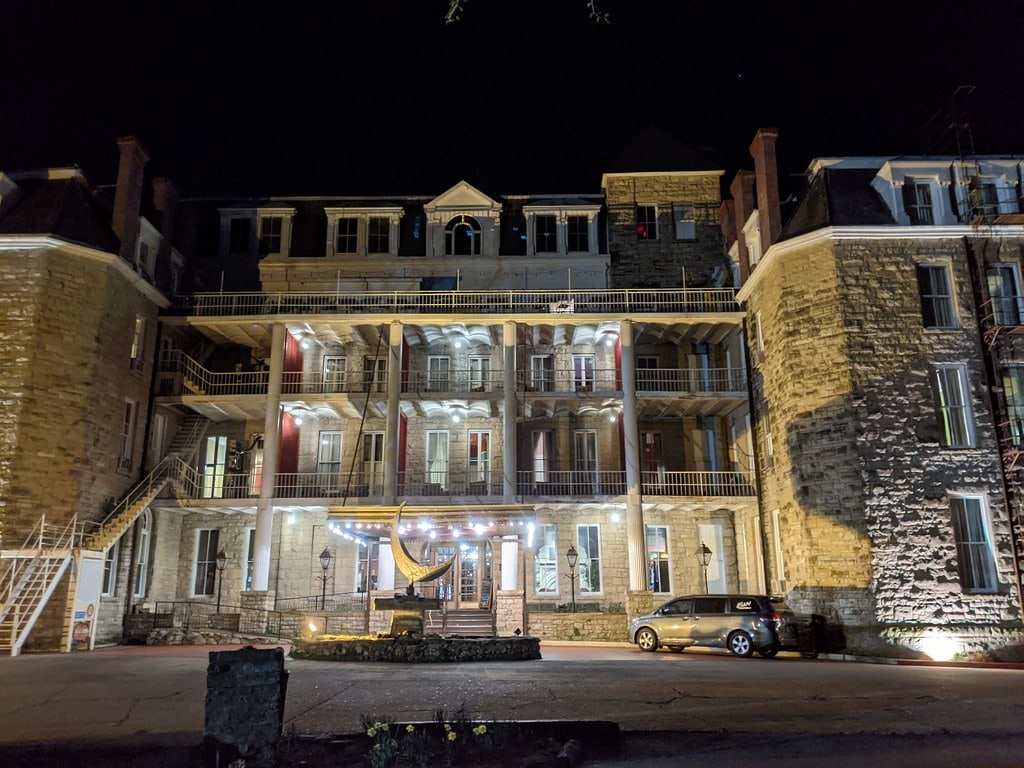

The Last Grand Hotel on the Hill

They built it for the millionaires. The Crescent Hotel opened in 1886, perched high over Eureka Springs, Arkansas, where fresh air, high ceilings, and natural springs were supposed to fix what ailed you.

But something else happened. The plans got too big, the investors lost steam, and the mountain didn't bend to business.

Over time, it became a college, then a hospital, and finally a ghost story. Few buildings in Arkansas have changed masks so many times - and kept them all.

Construction and Capital on West Mountain

The Crescent Hotel began in the early 1880s as a speculative real estate project backed by the Eureka Springs Improvement Company.

They wanted to attract wealthy travelers to the Ozarks, and they picked West Mountain because of its view and elevation.

Powell Clayton, a former governor and one of the key developers, hired St. Louis architect Isaac S. Taylor in 1884.

Taylor already had experience designing civic and industrial buildings.

For this hotel, he used limestone and steep gables, drawing in Victorian and French styles.

Construction crews broke ground in 1884 using 27-inch-thick stones quarried locally.

They finished the project in two years. Final cost: $294,000.

The grand opening was held in May 1886. That first summer, the hotel advertised its electric bells, hydraulic elevator, and fireplaces in every room.

St. Louis and San Francisco newspapers covered it as a luxury escape.

But from the beginning, operational issues cropped up.

The terrain made plumbing and heating inconsistent.

The steep hillside affected service routes. By the mid-1890s, occupancy declined.

By then, Eureka Springs' popularity as a resort town had already started to fade.

Still, the hotel remained open seasonally and continued to market itself as a high-end destination into the early 20th century.

For travelers searching for old buildings with real stories, the Crescent is still one of the more unusual things to do in Eureka Springs, Arkansas.

Classrooms in the Clouds - The College Conversion

By 1908, the Crescent Hotel had worn through its glamour.

Seasonal guests dwindled, and luxury didn't stick.

So local investors tried a new approach: turning the mountain resort into Crescent College and Conservatory for Young Women.

They pitched it as refined and secluded, a place for young women to study music, literature, French, and domestic science far from city noise.

The building hadn't changed much, and its old-world charm became part of its appeal.

Fireplaces stayed lit, balconies doubled as reading spots, and faculty lived upstairs.

Students wore uniforms. Promotional leaflets showed posed group shots and handwritten testimonials.

There was a piano in nearly every hallway.

It ran for 16 years, but the model never scaled.

The railroad lost traffic, regional demand shifted, and upkeep on a five-story limestone structure wasn't cheap.

Enrollment dropped, and the school shut down in 1924.

A junior college replaced it in 1930, which lasted until 1934.

Then, the owners pivoted again. There were no more classes, lectures, or tuition checks.

The Crescent returned to being a summer hotel, marketed now as quaint rather than grand.

Ads focused on cooler mountain air and privacy. There were no major renovations. There was no new capital.

By the mid-1930s, it was a building between purposes. Too elaborate for casual lodging, too fragile for business, too remote for a real revival.

The staff opened the doors each May and closed them by fall.

Most of the year, it sat quietly, waiting.

Fraud in the Ozarks - Baker's Cure-All Resort

In 1937, Norman G. Baker rolled into Eureka Springs with a suitcase full of fake medicine and a grudge against doctors.

He wasn't licensed or trained, but he had a knack for selling miracles and a crowd ready to believe him.

After getting run out of Iowa for unlicensed medical practice, he bought the Crescent Hotel and renamed it a cancer hospital.

He dressed in white, called himself "Doctor," and filled the halls with patients.

The hotel's old suites became sick rooms. Nurses in pressed uniforms walked the stone corridors.

A morgue was built in the basement. Baker's "cure" was a mix of corn silk, watermelon seed, clover, and carbolic acid.

He said it worked. He told them they'd be fine.

His ads ran across the country. Desperate families sent checks and bus tickets. There were no surgeries or radiation - just injections, water, and rest.

For a few years, it ran like clockwork until the feds showed up.

In 1940, Baker was convicted of mail fraud. The hospital closed that same year.

His miracle empire ended in court with a four-year prison sentence and a long list of patients who never left cured.

After that, the Crescent went dark. For nearly five years, the doors stayed shut.

There were no guests, staff, or plans. By 1946, it was back on the market - stripped, gutted, and waiting again.

Sales, Smoke, and Stone - The Midcentury Rebuild

The Crescent changed hands again in the spring of 1946.

Four buyers took it on: Herbert E. Shutter, John R. Constantine, Dwight Nichols, and Herbert Byfield.

They didn't have a new concept or bold plan - what they had was a cold, empty property.

That year, they reopened it quietly as a seasonal hotel.

The name stayed, and the layout didn't change. The past wasn't scrubbed, but it wasn't advertised either.

Then came March 15, 1967.

A fire broke out and tore through the top floors. It wasn't a total loss, but it came close.

By then, Nichols was the only surviving owner. There were no celebrity fundraisers or press tours.

He held onto the shell and tried to keep it standing.

Insurance covered repairs, but the hotel never fully bounced back during that stretch.

The property moved in and out of partial use through the 1970s and 1980s.

Tourists still came, though fewer each year. Local guides mentioned the morgue in hushed tones.

Restoration efforts happened in short bursts, usually tied to seasonal revenue.

A fresh coat of paint. New fixtures. Patchwork, mostly.

The business stayed under private ownership with minimal outside investment.

No corporate chains made offers, and no rebranding campaign was launched.

It sat in a holding pattern - one foot in preservation, the other in practical survival.

Enough to rent out rooms and keep the water running - barely.

By the 1990s, it was still standing, but unevenly.

Most guests came for the view, some asked about the ghosts, and most didn't hear the full story.

Reclaimed and Rewired - The Roenigk Renovation

In 1997, Marty and Elise Roenigk bought the Crescent Hotel for $1.3 million.

They weren't hotel developers. They lived in Eureka Springs and already owned the nearby Basin Park Hotel.

What they wanted was restoration - brick by brick, floor by floor.

They didn't gut it. They worked with what was there. The limestone walls stayed.

The layout stayed. Between 1997 and 2002, the Roenigks ran a quiet, staged renovation.

Plumbing, electric, structural reinforcements, room-by-room refurbishing - just steady work.

Marty Roenigk passed in 2009, but by then, the hotel was back in full operation.

Elise continued ownership. They kept the ghost tours. They leaned into the darker chapters but didn't rewrite them.

The former morgue was opened to visitors.

The original lab equipment from Baker's operation was set behind glass.

Staff logged visitor accounts and collected incident reports related to unexplained activity.

In 2005, the TV show Ghost Hunters filmed an episode inside the Crescent.

A thermal camera picked up what the crew labeled a "full-body apparition." After the episode aired nationwide, demand for rooms jumped.

The hotel's haunted label stuck - and kept growing.

But it wasn't just tourism. In January 2016, the Crescent Hotel was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Today, it is part of Historic Hotels of America, a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

But no one confused it with a resort chain. The bones of the old hotel are still there, even when the lobby fills up.

🍀

the paranormal tour here is absolutely A1..right up there with Waverly Hills in Kentucky..and it is absolutely haunted. many died there from recieving the fake care from the Dr who built the place originally..check it out u will not be disappointed

Thank you for your recommendation! It's great to hear that the Crescent Hotel lived up to its reputation. Sounds like a thrilling experience.