A Retail Powerhouse in the Making

The air outside is thick with Louisiana heat, the kind that sticks to your skin.

Cars shuffle in and out of the lot, their tires crunching against asphalt warmed by decades of retail traffic.

Oakwood Center stands where it always has - on the West Bank of the Mississippi, a shopping hub built for a time when malls were the center of everything.

Oakwood opened in 1966, part of a wave of suburban expansion that followed the completion of the Crescent City Connection.

Back then, it was called Oakwood Mall, a name some still use.

It was designed to be a destination, a place where families could spend an afternoon browsing store windows or cooling off in air-conditioned department stores.

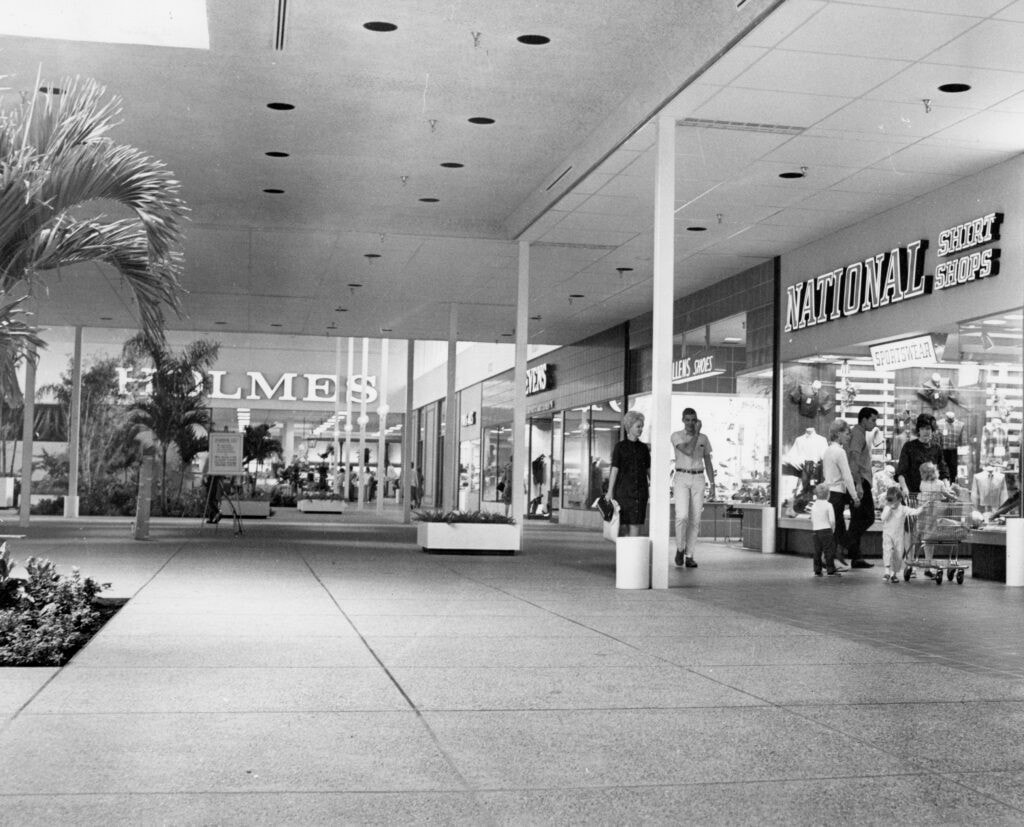

Sears was the first to open its doors, greeting shoppers on April 13, 1966. A few months later, D.H. Holmes followed, bringing upscale fashion to the West Bank.

Inside, the storefronts were a mix of local and national names - Goldring's, Gus Mayer, K & B Drug, McKenzie Pastry Shoppe.

S.H. Kress, a five-and-dime store, occupied 26,000 square feet and offered everything from fabric to housewares.

In a corner, Winn-Dixie filled carts with fresh produce and frozen dinners, an anchor in its own right.

By the 1980s, Oakwood wasn't just surviving - it was growing. D.H. Holmes expanded, adding a third floor in 1974.

The Rouse Company acquired the mall in 1982, pumping money into renovations. A new food court opened in 1984, carved from the space where Kress once stood.

The upgrades kept coming: Mervyn's, a California-based department store, arrived in 1986, taking over a west-end wing.

Shoppers had more choices, and for a while, Oakwood felt like the beating heart of retail on the West Bank.

People came here for more than shopping. It was where kids from Gretna and Terrytown wandered in packs after school, where teenagers got their first jobs folding sweaters at Stein Mart.

It was a backdrop for everyday life, woven into the rhythm of the city. Even now, with a changing retail landscape, some still consider it a top spot for things to do south of New Orleans, Louisiana.

The Fire That Nearly Took It All

The first break-ins happened while the wind still howled through the city. August 31, 2005 - two days after Hurricane Katrina made landfall.

The floodwaters never reached Oakwood Center, but the chaos did. Looters shattered glass, pried open security gates, and emptied cash registers that had already been cleaned out before the storm.

Then, the fires started.

Smoke rolled through the corridors, curling around displays that had stood untouched for years.

The flames spread fast - too fast. By the time emergency crews made it inside, it was too late. Eighty percent of the mall was damaged, either by fire or the water used to put it out.

Foot Locker, Dollar Tree, and the Bank of Louisiana were gutted. Dillard's and Sears, the mall's biggest anchors, stood blackened but intact.

For months, the building sat quiet, the scent of charred plastic still thick in the air.

Stores that had been a second home to shoppers were stripped to the studs. Some never reopened, and others took years. The cleanup started with Sears and Dillard's, both determined to bring the mall back.

They returned first, followed by Foot Locker and a handful of others.

Rebuilding a mall isn't like flipping a switch. The process stretched on, storefront by storefront. The official reopening was on October 19, 2007, two years after the fires, but not everything came back.

The Mervyn's wing, once home to one of the mall's busiest stores, remained boarded up.

It was the one part of the mall nobody seemed sure what to do with.

The Reinvention That Almost Worked

By 2013, the empty wing had become an eyesore. Mervyn's never returned, and the vacant space lingered - unfilled, in a mall still trying to show it hadn't stalled.

The solution came in the form of Dick's Sporting Goods - a brand with deep pockets, willing to take a gamble on a place that had already been through one disaster.

The old wing was demolished and replaced by a modern, two-story store with wide glass windows and neon signage.

Inside, Oakwood Center felt different. Forever 21 and Shoe Department Encore moved in, filling gaps left by stores that had never returned.

A food pavilion replaced the old cafeteria-style food court, offering more seating and a mix of national chains and local spots.

The mall's leasing team leaned into experience-based retail, bringing in stores that offered something beyond racks of clothes.

For a while, it worked. Shoppers returned, foot traffic picked up, and the mall felt - if not new - at least refreshed.

But retail was changing. The rise of online shopping chipped away at brick-and-mortar stores, forcing even the strongest names to rethink their strategies.

Then came 2017 and another blow. Sears, a store that had been there since the beginning, announced it was closing.

It wasn't just Oakwood - 104 locations shut down across the country. But here, on the West Bank, it meant something more.

The mall had survived hurricanes, fires, and economic downturns, but losing Sears felt like losing a piece of its foundation.

March 2017. Sears shut its doors, leaving behind 189,600 square feet of dead space - a shell of a store, lights out, gates pulled down - a question no one had an answer for.

The rest of Oakwood Center kept moving, but the weight of that empty anchor pressed down.

JCPenney, Dillard's, Dick's Sporting Goods - they held their ground. The food pavilion stayed busy; new stores filled some gaps.

But the rhythm had shifted. Foot traffic wasn't the same. Retail wasn't the same.

And the mall - still standing, still trying - was figuring out what survival looked like now.

A Mall Built for a Changing Market

Management pushed for more than retail. By 2025, Oakwood Center had adapted, bringing in services to keep foot traffic flowing.

The Louisiana Office of Motor Vehicles (OMV) opened a location inside the mall, pulling a different kind of visitor - residents needing licenses, registrations, and paperwork.

It wasn't a traditional mall business, but in an era when retail alone doesn't guarantee success, it made sense.

Events used to be a staple - holiday celebrations, pop-ups, and promotions that turned casual shoppers into repeat visitors.

Now, the mall's event calendar is thinner. Oakwood still hosts seasonal sales and back-to-school promotions, but it's quieter.

Shoppers notice. Reviews online mention a lack of energy, a space that feels "half-full" on weekdays.

The lights are still on. Shoppers drift through - some after sneakers, some after a meal, some just there to renew a license.

The mall keeps going, deal by deal, tenant by tenant, holding on to whatever keeps the doors open.

The Future of Oakwood Center

Retail is always changing. Stores come and go, trends shift, and malls either evolve or disappear.

Oakwood Center sits at a crossroads - surrounded by history, shaped by disaster, and still looking for the next move.

The 2024 holiday season proved that, at least for now, people still want to shop in person.

Foot traffic surged, and cash registers rang up more sales than expected. For a few weeks, Oakwood felt like it did in its strongest years - full, alive, buzzing with energy.

Dillard's and JCPenney remain strongholds, but their futures depend on forces beyond the West Bank.

Department stores everywhere are shrinking, closing locations, and streamlining operations.

Dick's Sporting Goods holds steady, pulling in families, athletes, and deal hunters.

But the question remains: What happens to the spaces that don't fill back up?

Malls thrive when they adopt this model. Across the country, struggling centers turn to mixed-use development - hotels, apartments, and offices built into former retail spaces.

It hasn't happened at Oakwood yet, but the model is there.

For now, Oakwood Center stands, waiting for its next chapter. The mall's past proves one thing - it doesn't go down easily.

I love Oakwood Mall n grew up in it during 1973, 80s, 90s, n even till this day. please never let it shut down. maybe put some entertainment parks for Mom n kids. and bring in Arcade games for teens again... n I miss that store Suncoast videos that had movie

memory items. I live365 store for all types of jeans n cheap stuff! So much fun. if marketing has part time job openings, let me know.

The best malls adapt, and Oakwood could still thrive with the right mix of stores and fun. Arcades, local shops, and entertainment could bring back the energy it used to have.

see the mall soon :smile:❤️❤️❤️

:smile:❤️❤️❤️

Hope it's still as good as you remember!