Iconic Maine Foods: A Taste of the Pine Tree State

Maine is famous for its rugged coastline, lighthouses, and seafood, especially lobster. If there's one food that defines the state, it's Maine lobster, pulled fresh from the icy Atlantic and served in everything from rolls to chowder. But there's more to Maine's food scene than shellfish. Walk into a local diner, and you'll find whoopie pies, two chocolate cake rounds with a creamy filling that Mainers have claimed as their own.

Drive up north, and you'll pass endless stretches of wild blueberries, the tiny, sweet berries that end up in pies, muffins, and even beer.

Visit a backyard cookout, and someone might hand you a red snapper hot dog, bright red and packed with smoky flavor.

Maine's food traditions are built on local ingredients and a strong sense of place.

Foraged fiddleheads pop up on spring menus, baked beans simmer in pots on Saturday nights, and Moxie, Maine's official soda, remains a love-it-or-hate-it drink.

Whether it's fresh seafood, farm-grown produce, or nostalgic comfort food, Maine's flavors come with history, tradition, and a whole lot of local pride.

Lobster - Maine's Most Iconic Seafood

Maine and lobster go hand in hand. The state's cold, rocky waters create the perfect environment for these crustaceans, making Maine one of the largest suppliers of lobster in the world.

Fishermen haul in thousands of pounds daily, using traditional lobster traps that have remained largely unchanged for generations.

The Maine Lobster Festival, held every August in Rockland, celebrates this deep-rooted industry with cooking contests, lobster dinners, and the famous Great International Lobster Crate Race.

One of the most famous ways to enjoy Maine lobster is the lobster roll.

It's simple but perfect, chunks of fresh lobster, lightly dressed with either melted butter or a bit of mayonnaise, stuffed into a split-top bun.

Some people prefer the "Maine style" roll, served cold with mayo, while others go for the "Connecticut style," which is served warm with butter.

Either way, it's a staple at seafood shacks and roadside stands across the state.

For those looking for a more traditional meal, whole steamed lobster is the way to go.

Crack open the bright red shell, dip the tender meat in butter, and enjoy.

Many restaurants offer a classic "shore dinner," which pairs lobster with steamed clams, corn on the cob, and a side of drawn butter.

Lobster isn't just for fancy meals. In Maine, you'll find it in everything from lobster mac & cheese to lobster stew, a creamy, buttery dish loaded with fresh meat.

There's even lobster pizza, which combines the delicate sweetness of the meat with melted cheese and garlic.

While lobster is now a luxury food, it wasn't always this way. In the 1800s, it was considered "poor man's food," often fed to prisoners and servants.

That changed as people outside of Maine discovered its rich, buttery taste.

By the early 20th century, demand skyrocketed, and it became a sought-after delicacy.

Today, the Maine lobster industry supports thousands of fishermen, and sustainability efforts ensure it will continue for generations.

No visit to Maine is complete without trying fresh lobster, whether from a waterfront shack or a fine-dining restaurant.

Some locals even swear by eating it right off the boat; nothing beats lobster that's been pulled from the ocean just hours before.

Wild Blueberries - Small But Packed with Flavor

Maine might be known for seafood, but its wild blueberries are just as important.

These tiny, deep-blue berries cover thousands of acres across the state, thriving in the sandy, acidic soil left behind by glaciers.

Unlike the larger, cultivated blueberries found in grocery stores, Maine's wild variety is smaller, sweeter, and loaded with antioxidants.

Maine produces more wild blueberries than any other state, with over 40,000 acres of wild blueberry fields, mostly in the Downeast region.

The berries ripen in late summer, and farmers harvest them using a traditional metal rake with comb-like tines.

This method, which dates back over a century, allows workers to gently scoop up the berries without damaging the low-growing plants.

Some fields have been producing for generations, with families passing down the practice of blueberry farming.

One of the most popular ways to eat them is in blueberry pie, which is also Maine's official state dessert.

A good blueberry pie has a flaky crust, a generous filling of fresh berries, and just enough sugar to bring out the natural sweetness.

Some people like to add a scoop of vanilla ice cream or a dollop of whipped cream, but many Mainers will tell you it's perfect on its own.

Beyond pie, wild blueberries find their way into pancakes, muffins, jams, and even beer.

Breweries across Maine have embraced the berry, crafting unique blueberry-infused ales that offer a balance of sweetness and tartness.

The fruit is also used in wines, giving a distinct, slightly earthy flavor that pairs well with cheese and seafood.

Every August, the Maine Wild Blueberry Festival takes over the town of Machias.

This festival celebrates the harvest with pie-eating contests, baking competitions, and live music.

Farmers and locals come together to showcase the best blueberry treats, from classic jams to inventive dishes like blueberry barbecue sauce.

Maine's wild blueberries have a deep history. Indigenous Wabanaki people harvested them long before European settlers arrived, using them in stews, dried mixtures, and medicinal remedies.

Today, they remain an essential part of the state's agriculture and food culture.

With their intense flavor and natural sweetness, wild blueberries stand out from anything you'll find in the supermarket.

Whether baked into a dessert, blended into a smoothie, or eaten by the handful straight from the bush, they bring a taste of Maine's landscape to every bite.

Whoopie Pies - Maine's Favorite Sweet Treat

Walk into any bakery or gas station in Maine, and you'll probably see whoopie pies stacked on the shelves.

These classic desserts look like oversized sandwich cookies, but instead of crunchy wafers, they have two soft, cake-like rounds filled with a sweet, creamy center.

While Pennsylvania and a few other states claim to have invented whoopie pies, Maine has made them part of its food identity.

In fact, in 2011, the state officially declared the whoopie pie its official state treat.

A classic Maine whoopie pie has chocolate cake on the outside and a fluffy vanilla filling inside.

Some versions use buttercream, while others stick with a marshmallow-based filling.

Either way, the texture is soft, slightly sticky, and easy to eat by hand.

Bakers also get creative, offering flavors like pumpkin, peanut butter, and maple, especially in the fall.

One of the oldest bakeries known to make whoopie pies in Maine is Labadie's Bakery in Lewiston, which has been selling them since 1925.

Demand has grown over the years, and now they're found in grocery stores, diners, and roadside stands all over the state.

Some bakeries even make giant versions, big enough to serve as a birthday cake.

The origins of the whoopie pie aren't completely clear. Some say it started with the Pennsylvania Dutch, while others believe it came from Amish communities before spreading to New England.

What's certain is that Maine took the dessert and ran with it. Now, it's one of the state's most recognizable foods, right alongside lobster and blueberries.

Maine celebrates its love for whoopie pies every year at the Maine Whoopie Pie Festival in Dover-Foxcroft.

Thousands of people attend to taste different variations, enter eating contests, and vote on their favorites.

Vendors sell everything from traditional chocolate to experimental flavors like s'mores and salted caramel.

For Mainers, whoopie pies aren't just a dessert, they're a piece of local culture.

Whether homemade or store-bought, they're a go-to treat for lunchboxes, road trips, and celebrations.

Some bakeries ship them nationwide, but they always taste best fresh from a Maine bakery.

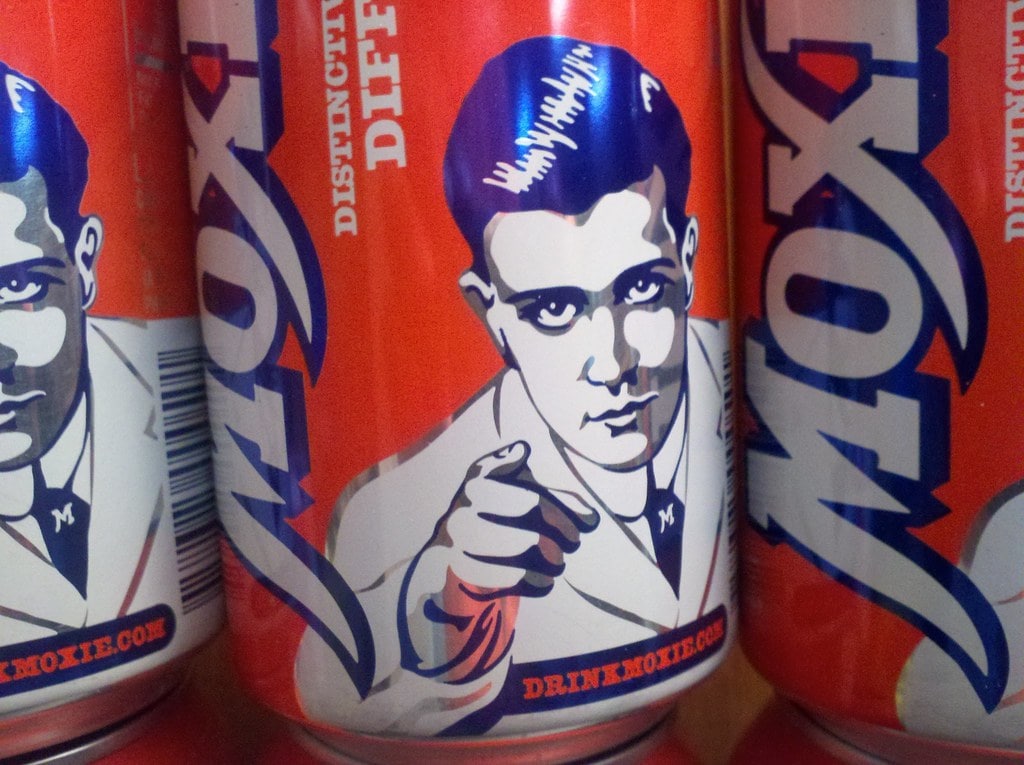

Moxie - Maine's Unique Soft Drink

Maine has its soda, and it's called Moxie. Unlike the sugary colas most people are used to, Moxie has a bitter, herbal taste that people either love or hate.

It was invented in 1876 by Dr. Augustin Thompson, a Maine-born pharmacist who originally marketed it as a tonic for nerves and digestion.

By the early 1900s, Moxie had become one of the first mass-produced soft drinks in the country, even outselling Coca-Cola at one point.

What makes Moxie stand out is its main ingredient, gentian root extract. This gives it a distinct, slightly medicinal flavor that lingers after each sip.

Some describe it as a mix between root beer and cough syrup, while others compare it to bitter herbal liqueurs. Either way, it's a taste that sticks with you.

In 2005, Maine made Moxie its official state soft drink, cementing its place in local culture.

Despite its divisive flavor, it has a dedicated following, and it's available in supermarkets, convenience stores, and diners all over the state.

Some restaurants even use it in recipes, adding it to barbecue sauces, milkshakes, and even cocktails.

Every summer, the town of Lisbon hosts the Moxie Festival, a three-day event dedicated to celebrating the drink.

There will be a Moxie chugging contest, a Moxie recipe competition, and a parade featuring floats decorated with the brand's signature orange-and-black colors.

The festival draws thousands of visitors, many of whom travel from out of state just to stock up on cases of the soda.

Even though Moxie isn't as popular as it once was, it still has a loyal fan base.

Some Mainers grew up drinking it and wouldn't have it any other way. Others try it once and never touch it again. Either way, Moxie is part of Maine's food history, bold, unexpected, and completely its own thing.

Red Snapper Hot Dogs - Maine's Brightly Colored Classic

Maine's red snapper hot dogs stand out immediately. They're bright red, wrapped in a natural casing, and have a crisp snap when you bite into them.

Found in grocery stores, food trucks, and backyard cookouts, these hot dogs are a local favorite that's been around for over a century.

The name "red snapper" comes from both the color and the way the casing snaps when you take a bite.

Unlike the pale, smooth hot dogs found elsewhere, these are dyed red and have a firm, snappy texture.

Some say the tradition of coloring them started to make them more appealing, while others believe it was just a way to distinguish them from other varieties.

One of the best-known producers of red snappers is W.A. Bean & Sons, a Bangor-based company. Their recipe hasn't changed much: pork and beef, mild seasoning, and that signature red casing.

While hot dogs are available year-round, they're especially popular in the summer, appearing at cookouts, fairs, and beachside food stands.

In Maine, hot dogs are usually grilled or steamed and served in New England-style split-top buns.

Unlike standard hot dog buns, these have flat sides, making them perfect for toasting with butter.

Toppings are pretty simple; most people go for mustard, relish, or chopped onions.

Ketchup is an option, but traditionalists tend to stick with the basics. Some restaurants take it a step further, serving red snappers in baked bean casseroles or slicing them up for breakfast hash.

Others deep-fry them, which gives the casing an even crispier texture. No matter how they're cooked, they have a loyal following.

For many Mainers, red snappers are more than just hot dogs; they're part of childhood memories, summer traditions, and simple, everyday meals.

Whether bought from a roadside stand or cooked over an open flame, they're a classic part of Maine's food culture.

Fiddleheads - A Seasonal Wild Green

Every spring, Maine's forests and riverbanks come alive with fiddleheads, young, coiled ferns that taste like a cross between asparagus and spinach.

Foraging for these bright green spirals is a long-standing tradition, with many families heading out to secret spots to gather them as soon as the snow melts.

Fiddleheads come from the ostrich fern, a plant that grows in damp, shady areas near streams and riverbanks.

The ferns sprout in early April and May, but they have a short harvesting window; once they unfurl into full leaves, they lose their tender texture and unique flavor.

Because of this, fiddlehead season doesn't last long, and Mainers take full advantage while they can.

Foraging is part of the fun. Many people have favorite picking spots that they keep secret, passing them down through generations.

The key is to harvest them correctly; only taking a few from each plant ensures that the ferns keep growing year after year.

Once harvested, fiddleheads need to be cleaned and cooked properly. Raw fiddleheads can carry bacteria, so they're always boiled or steamed before eating.

Most people keep the preparation simple, a quick sauté with butter and garlic, a dash of salt and pepper, or a squeeze of lemon.

Others add them to soups, pasta dishes, or even omelets. Their slightly grassy, nutty taste makes them a versatile addition to many meals.

Fiddleheads have been part of Maine's food history for centuries. The Wabanaki people, who have lived in the region for thousands of years, were among the first to harvest and cook them.

Early European settlers also adopted the tradition, and over time, fiddleheads became a seasonal delicacy in New England.

While you can sometimes find fiddleheads at farmers' markets and grocery stores, many people still prefer to pick their own.

Local restaurants also feature them on menus for a few weeks each year, often pairing them with seafood or serving them as a side dish.

For those lucky enough to get their hands on fresh fiddleheads, they offer a taste of Maine's wild landscape.

The season may be short, but foraging, cooking, and enjoying them is a tradition that brings people back to nature and to the dinner table every spring.

Baked Beans - A Saturday Night Tradition

Baked beans have been a part of Maine's food culture for generations. Slow-cooked with molasses and salt pork, they have a deep, slightly sweet flavor that pairs well with hearty meals.

Many families still follow the old tradition of serving baked beans on Saturday nights, often with brown bread or hot dogs on the side.

Maine's baked beans have a long history, dating back to the Native Wabanaki people, who cooked them in clay pots with bear fat and maple syrup.

When English settlers arrived in the 1600s, they adapted the recipe by using pork fat and molasses, ingredients that became common due to trade with the Caribbean.

Over time, the dish became a staple of New England cuisine, with each region adding its own twist.

Maine's version usually starts with yellow-eye beans, a variety known for its creamy texture and mild flavor.

The beans are soaked overnight and then slow-cooked for hours, sometimes all day, to develop the perfect consistency.

Many old-school cooks still use a bean hole, a method where beans are buried in hot coals and left to cook underground.

This technique dates back to early settlers and is still practiced at some community suppers.

Speaking of community gatherings, bean suppers are a well-known tradition in Maine.

Churches, firehouses, and town halls regularly host these events, where locals come together to enjoy homemade baked beans, brown bread, coleslaw, and sometimes red snapper hot dogs.

The meals are usually cheap, filling, and a great way for people to connect.

Brown bread is another piece of the baked bean tradition. Made with a mix of cornmeal, whole wheat flour, and molasses, it's dense, slightly sweet, and often steamed rather than baked.

Some people cook it in tin cans, giving it a unique cylindrical shape. Served warm with butter, it complements the beans perfectly.

While canned baked beans are easy to find in stores, many Mainers still prefer to make their own.

The slow cooking process allows the beans to absorb all the flavors, creating a rich and comforting dish.

Whether cooked in a modern oven or buried in a bean hole, baked beans remain a classic part of Maine's weekend meals.

The Italian Sandwich - Maine's Classic Deli Sub

If you order an "Italian" in Maine, don't expect pasta or meatballs. Instead, you'll get a sub-style sandwich packed with ham, cheese, and fresh vegetables, all drizzled with oil and served in a soft roll.

This sandwich, often called a "Maine Italian," has been a lunchtime favorite for over a century.

The story of the Italian sandwich begins in Portland in 1902 when Giovanni Amato, an Italian immigrant, started selling fresh-baked rolls to dockworkers.

At their request, he began filling them with meat, cheese, and vegetables, creating what would become Maine's most famous sandwich.

His shop, Amato's, still serves them today, using the same recipe that made them popular.

A classic Maine Italian sandwich includes ham, American cheese, green peppers, onions, tomatoes, pickles, and black olives, all topped with a drizzle of oil.

The roll is soft and chewy, made fresh daily. Unlike many deli sandwiches, this one doesn't include mayo or mustard, just oil, which keeps the flavors light and fresh.

While the traditional version remains popular, sandwich shops across Maine offer variations.

Some people swap out the ham for turkey, salami, or roast beef. Others add hot peppers for an extra kick. No matter the twist, the key ingredients remain the same: fresh bread, crisp vegetables, and just the right amount of oil.

Maine Italians are widely available at local sandwich shops, corner stores, and even gas stations.

Chains like Amato's have expanded beyond Portland, but many small delis still make their version.

In some families, picking up an Italian sandwich for lunch or a road trip is as routine as grabbing a cup of coffee.

Unlike the more famous Philly cheesesteak or New York pastrami, the Maine Italian remains a regional favorite.

It's not as well-known outside of New England, but within the state, it's a sandwich that's been passed down through generations.

Whether wrapped in paper from a neighborhood deli or picked up from a convenience store, the Maine Italian sandwich remains a go-to meal for locals looking for something quick, filling, and familiar.

Potato Donuts - Maine's Unexpected Bakery Staple

Maine has a deep connection to potatoes. The state's Aroostook County produces millions of pounds of them each year, making potatoes a key ingredient in local dishes.

While people expect to find them in mashed potatoes or fries, many are surprised to learn that Maine also uses them in donuts.

Potato donuts, sometimes called "spud nuts," are a local favorite. They have a denser and softer texture than traditional cake donuts.

The idea of adding mashed potatoes to donut batter isn't new. Some believe it started in the early 1900s when bakers found that potatoes made their pastries extra moist without being greasy.

Unlike standard flour-based donuts, these have a slightly chewy inside with a crisp golden-brown exterior.

The potato starch helps keep them fresher longer, which may be why they've remained a favorite in Maine's bakeries.

One of the best-known places for potato donuts is The Holy Donut, a Portland-based shop that has gained a following for its creative flavors.

The bakery opened in 2012. It uses locally grown potatoes to make donuts in varieties like dark chocolate, sea salt, maple, and Maine blueberry glaze.

While the ingredients are simple, potatoes, flour, eggs, and sugar, the result is a donut with a unique texture that's both rich and light.

Other bakeries and home cooks across Maine also make their versions. Some stick with classic flavors like cinnamon sugar and plain glazed, while others experiment with toppings like bacon crumbles, espresso drizzle, or even coconut flakes.

Aroostook County, known for its potato farms, hosts potato festivals during which vendors sell fresh batches of donuts, often alongside other potato-based treats like fries and pancakes.

Potato donuts can be fried or baked, though frying gives them their signature crisp exterior.

Most recipes call for mashed potatoes rather than raw potato flour, which keeps them soft and tender.

Some families pass down their variations, adding vanilla, nutmeg, or a splash of buttermilk to the mix.

While many donut shops offer standard yeast or cake varieties, Maine's potato donuts stand out for their history and texture.

They may look like any other donut at first glance, but one bite reveals their difference: fluffy, slightly chewy, and just the right amount of sweet.

Haddock - Maine's Favorite White Fish

Maine's cold waters are home to some of the best seafood in the country, and haddock is one of the most popular choices.

This flaky white fish is mild, slightly sweet, and versatile enough for frying, baking, or chowder-making.

Many seafood restaurants along the coast serve it daily, often as part of fish and chips or in a creamy haddock stew.

Haddock belongs to the cod family but has a firmer texture and thinner fillets.

Unlike cod, which is sometimes overfished, haddock remains plentiful in the Gulf of Maine, making it a sustainable choice for local fishermen.

The fish has been a staple in Maine's diet for centuries, going back to the days when early settlers relied on the sea for food.

One of the most common ways to eat haddock in Maine is fried haddock sandwiches.

The fish is lightly battered, deep-fried until golden, and served on a soft bun with lettuce, tartar sauce, and sometimes a squeeze of lemon.

Many diners and seafood shacks offer this sandwich as a lunchtime favorite, often alongside fries or coleslaw.

Another traditional dish is haddock chowder, a creamy soup made with chunks of haddock, potatoes, onions, and milk or cream.

This dish has been a part of New England's food culture for generations, especially in fishing communities where fresh haddock is easy to find.

Unlike clam chowder, haddock chowder has a lighter, more delicate flavor, making it a comforting meal on cold days.

Many people choose baked haddock, often topped with butter, lemon juice, and breadcrumbs, as a healthier option.

The fish absorbs flavors well, so variations include toppings like garlic, herbs, or even crushed crackers for added crunch.

Baked haddock is a common dish at home and in restaurants, especially those that focus on fresh, locally caught seafood.

Maine's haddock industry continues to thrive, with fishermen landing thousands of pounds every year.

Many local markets sell it fresh, while some companies also distribute it frozen to other states.

With its mild taste and versatility, haddock remains one of Maine's most reliable and well-loved fish.

Whether served fried, baked, or in a rich chowder, it's a seafood staple that reflects the state's deep connection to the ocean.