Bricks, Memory, and the Oldest House in Trenton

William Trent House draws you in before you hit the main steps.

A brick wall runs along the property, close to Market Street, and the grass nearby shows signs of many events and quiet days.

Built in 1719 for a Philadelphia merchant, the house stands where the Lenni Lenape once lived, then Quaker hands worked the ground, and later, the city of Trenton grew up around it.

The front doors are double and arched, and inside the hallway, the original wood shows wear from hundreds of years.

People visit for ice cream socials in June, talks about soldiers in February, and to see the old cupola that shows the building's long past in New Jersey.

A Merchant's Legacy

William Trent bought 800 acres in 1714. He got the land from the son of Mahlon Stacy, who had owned it since the 1680s.

Stacy was a Quaker who built a mill along the Assunpink Creek.

Trent worked in shipping in Philadelphia and wanted land near the river. The brick house was done by 1719.

It was large for the time, with a hip roof and five window bays. The front door had a six-light transom.

Behind the walls, there were four chambers per floor and a central staircase.

He planted a straight line of cherry trees from the front path to the river ferry.

In 1720, Trent laid out a few streets close by. He named the place "Trent Town." The name stuck.

By 1721, his family was living there full-time, but William Trent passed away in 1724.

The land once included mills, some other buildings, and a ferry dock. Only the house remains.

Today, the building sits at 15 Market Street, with brick fencing and a narrow strip of lawn.

Inside, the staircase and some floors are original. The house has kept its early layout and roofline for over three centuries.

Rented, Reused, and Repainted

After William Trent died, the house was owned by a series of private individuals.

Records are incomplete, but three governors lived in the house.

Lewis Morris, Rodman Price, and Philemon Dickerson each spent time in the house during their careers.

The structure was still standing during the American Revolution.

It was home to Colonel John Cox and Dr. William Bryant at different times, both of whom were involved locally during the war. No battles were fought inside the house.

Most of the changes in the 1800s came from new owners.

They made repairs but kept the brick walls and central hall. The original woodwork stayed in some rooms.

The layout did not change much, even as the purpose of the house did.

By the 1900s, the house was older than most others in Trenton.

It sat near what would later be Route 29. The ferry and mills had already disappeared.

The front steps, brickwork, and main floor plan stayed the same.

The city kept growing around it. William Trent House stayed in place.

The Museum Clause and a 1930s Reset

In 1929, Edward A. Stokes gave the William Trent House to the city.

His donation came with terms. The building had to be restored to its early look.

It could only be used as a museum, art gallery, or library.

By 1934, work had begun. Workers took off the later additions and repaired the old brick.

The wood floors and the stair rail stayed. The rooms inside were cleared out, but the floor plan did not change.

The goal was to restore it to its appearance around 1720.

Work finished in 1936. There was no overnight rush. The process took two years. It used parts of the original frame.

The building was dedicated in 1936. It opened as a museum in 1939.

In the years after, the museum added displays and kept the property open to the public.

The renovation in the 1930s shaped what is there today: a fenced yard, a brick exterior, and narrow steps at the entrance.

The cherry trees are gone, but the windows still sit tight under a dentil-lined cornice.

The house is still where Trent put it, one block from the river.

Registry Listings and Recognition in Print

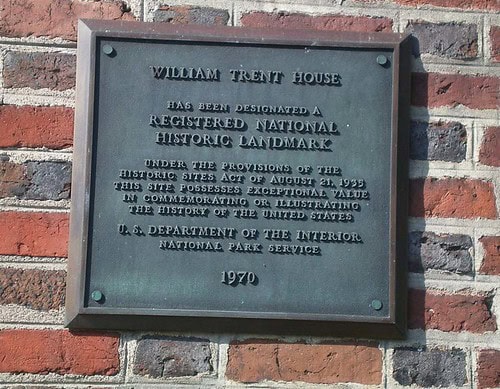

On April 15, 1970, the William Trent House became a National Historic Landmark.

It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on the same day.

The federal listing focused on its age, architecture, and link to the city's founding.

The National Park Service called out its Georgian style and early urban role.

A year later, on May 27, 1971, the house was added to the New Jersey Register of Historic Places.

Both listings secured protection and opened the door to grants. They also raised public visibility for the site.

In the decades that followed, the museum leaned on these designations to build programs.

It hosted talks, walking tours, and temporary displays.

The story of colonial Trenton was kept at street level, inside the same brick walls Trent once walked.

Each new program followed the same intent laid out in the 1930s.

Use the building to anchor stories that began when the city had fewer roads and no tracks at all.

Closed for Repairs, Reopened with Care

In June 2024, the William Trent House closed for system work. The job was clear: fix the HVAC.

Heat and moisture had started to wear on old wood and plaster.

The museum required a climate control system that could protect the structure year-round.

On February 20, 2025, the house reopened.

The fix was funded by the New Jersey Historic Trust with matching city funds.

The house was returned to public use with improved air quality but no new marks.

Summer 2025: Cones, Chairs, and History Talks

The first public event after the February reopening landed on June 1, 2025.

That date marked 86 years since the William Trent House opened as a museum in 1939. From 1 to 4 pm, families stopped by for the annual ice cream social.

Crafts and games filled the lawn. A folding table held the cones. Tours ran in short loops inside the house.

A month later, on July 6, the visitor center hosted a history talk. Paul Soltis walked through Washington's 1775 march through New Jersey.

The presentation marked 250 years since Washington took command of the Continental Army.

The room stayed full.

An exhibit called "Oh Freedom!" filled the back wall. It traced the stories of Black soldiers during and after the war.

The material came from Kean University and Crossroads of the American Revolution.

🌻