Origins of the Kings Park Asylum

In 1885, Kings County officials turned to Suffolk County's open land to relieve Brooklyn's overcrowded asylums.

The site, nestled between rolling fields and the Nissequogue River, seemed ideal, a place where fresh air and farm work could mend fractured minds.

Here, the Kings County Asylum was born, its mission clear: to break from the grim, neglected hospitals of the past.

Patients would work the land, feed livestock, and move within an orderly, self-sustaining world.

This, it was believed, would bring them peace.

By 1889, the asylum had taken root. Sixteen cottages, a laundry, a heating plant, and a barn formed the heart of a growing institution.

The population swelled to 450.

In the mornings, the scent of damp earth rose from the tilled fields, mixing with the sharp tang of coal smoke from the boilers.

The clang of metal pails, the shuffle of boots in the dirt, the lowing of cattle, these sounds defined life inside the gates.

The asylum was not yet the looming specter it would become.

For a time, it was simply a place where work and routine softened the edges of disordered minds.

But the stillness of the land could only last so long.

By 1895, New York State assumed control. The facility was renamed Kings Park State Hospital, and with the new title came expansion.

The surrounding town, once Indian Head, adopted the hospital's name, its identity tied to the growing asylum.

A Long Island Rail Road spur was laid, its iron veins feeding the institution with supplies and new arrivals.

The hospital generated its own power, housed its own staff, and built outward, then upward.

More land, more buildings, more bodies. What had begun as a farm colony had become something vast and inescapable.

And with that growth, something else settled in.

The wind whistled through the narrow alleyways between buildings, carrying whispers through the barred windows.

Shadows stretched across the corridors, long and thin, even when no one stood to cast them.

The patients still worked and still moved through the daily rituals of their existence, but something about the asylum had changed.

The town outside carried on, but within these walls, time thickened.

The past did not fade here. It gathered, pressing into the peeling paint, settling deep into the brick.

Expansion and Transformation

The land was no longer enough. As the 20th century unfolded, Kings Park State Hospital swelled beyond what its founders had imagined.

By the 1930s, its network of low-slung cottages and farmhouses could no longer contain the growing number of patients.

The state's response was stark: build higher. Build stronger.

The hospital's campus became a landscape of towering brick monoliths, shadowed corridors, and windowless wards.

In 1939, the hospital unveiled its most infamous structure, Building 93.

Thirteen stories of cold, institutional grandeur, its towering form was meant to house geriatric and chronically ill patients.

Designed by state architect William E. Haugaard, its construction was funded by the Works Progress Administration.

But something about it unsettled even those who worked within its walls.

Its height loomed over the rest of the campus, the last stop for many who entered its doors.

By the 1940s, Kings Park had become a world unto itself.

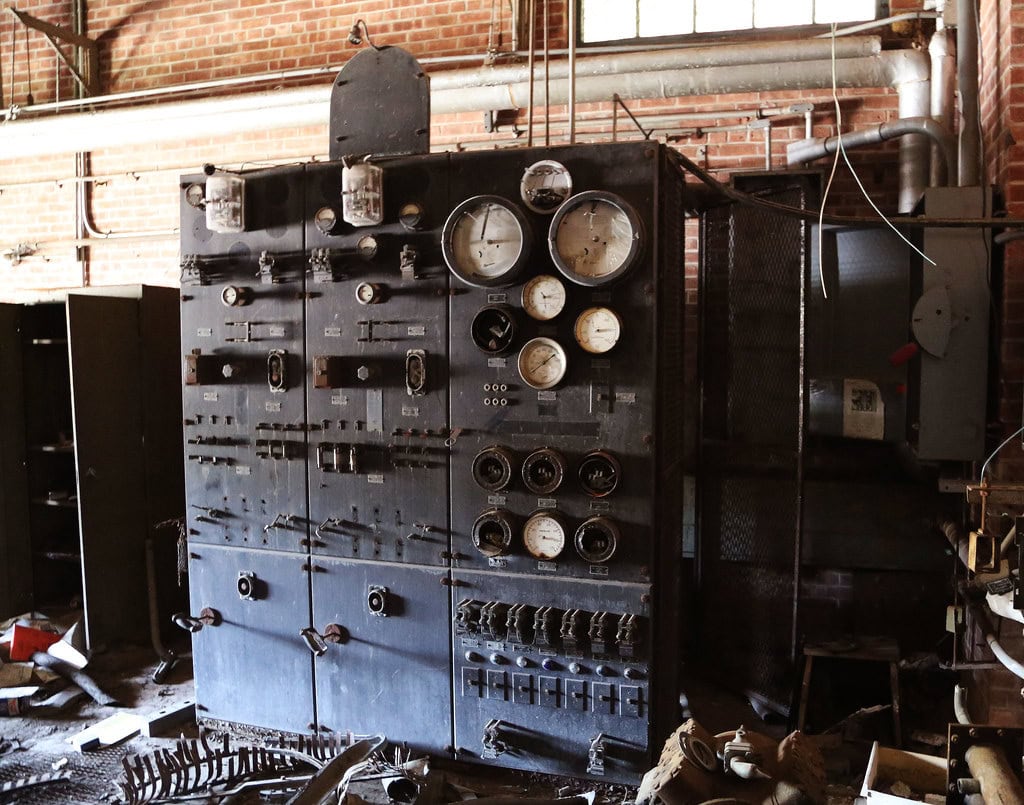

The hospital ran its own power plant, water treatment facility, and even its own Long Island Rail Road spur to ferry in food, supplies, and, most notably, patients.

The town outside was no longer separate from the institution.

The asylum dictated its rhythms, workforce, and very identity.

Nurses and attendants lived in rows of identical cottages, and doctors occupied stately houses on the hospital grounds.

Then came the war. The 1940s and early '50s saw a surge in patient numbers, with World War II veterans swelling the asylum's ranks.

The halls of Kings Park Asylum grew louder and more crowded.

By 1954, the patient population exceeded 9,300.

The idyllic notion of rest and labor had long since faded.

Now, treatments have become invasive, prefrontal lobotomies and electroshock therapy.

The hospital, built on the promise of gentle rehabilitation, had become something else entirely.

Decline and Closure

The tide began to turn in 1955. That year, a new drug, Thorazine, changed everything.

For the first time, severe mental illness could be controlled with medication rather than confinement.

The locked wards of Kings Park grew quieter, and the beds emptied.

By the late 1960s, the state's mental health policy had shifted.

The great asylums were no longer seen as sanctuaries but as relics of an outdated system.

The push for deinstitutionalization began, and Kings Park was no exception.

Throughout the 1970s, the hospital's population shrank.

Activists and legal battles furthered the effort to close large psychiatric institutions, arguing that patients could live fuller lives in smaller community centers.

But these centers were never built in the numbers needed.

Many who left Kings Park found themselves adrift, homeless, struggling, or locked away again, this time in prisons instead of hospitals.

By the early 1990s, Kings Park Psychiatric Center had become a hollowed-out version of itself.

Entire wings stood empty. The great red-brick structures that had once hummed with life now echoed with silence.

Building 93, once a symbol of the hospital's expansion, had its upper floors sealed off.

The first few stories remained in use, but the walls above sat dark and untouched, gathering dust.

The end came in 1996.

The New York State Office of Mental Health ordered Kings Park's closure, transferring the last patients to Pilgrim Psychiatric Center.

The buildings were abandoned, the power cut, doors locked, and windows boarded, but something remained.

Locals whispered of lights flickering in empty rooms, figures glimpsed through broken glass, and the wind carrying voices where none should be.

Abandonment and Decay

When the last patients were transferred out of Kings Park Psychiatric Center in 1996, the buildings were not simply empty, they were left behind, forsaken.

The doors were locked, but time still found its way in.

Water crept through cracked ceilings, spreading damp rot through the walls.

Windows shattered, their jagged edges reflecting nothing but dust and ruin.

The wind, unchallenged, howled through hollow corridors where voices once murmured, where footsteps once fell.

Some buildings vanished. In the early 2000s, New York State sought to erase the most dangerous remnants of the hospital.

Fifteen structures were demolished, their remains buried in forgotten basements.

But the disturbed land did not settle quietly, asbestos, remnants of old heating systems, and buried industrial waste complicated redevelopment plans.

The old powerhouse, with its smokestack towering over the grounds, was demolished in 2013.

It collapsed in a controlled explosion that sent echoes rolling across the landscape.

Even in death, Kings Park did not go quietly.

For those who lingered in its shadow, the hospital's presence never truly faded.

Vandals slipped past rusted fences, leaving their marks in thick layers of graffiti.

The scent of mildew and decay mixed with spray paint is a testament to time and trespass.

Paranormal seekers wandered through the ruins, drawn by whispers of hauntings and the uneasy silence that wrapped around the institution's bones.

Some claimed to hear faint cries from the upper floors of Building 93.

Others swore they saw movement in the windows of long-abandoned wards, the quick flicker of a shape that should not be there.

Though much of the old hospital grounds have been absorbed into Nissequogue River State Park, the abandoned buildings remain.

They watch. They wait.

And for those who dare to step too close, Kings Park still speaks, in the rustling leaves, in the creaking of unseen doors, in the feeling that one is never truly alone.

Legends and Paranormal Activity

Kings Park Psychiatric Center is more than a ruin, it is a ghost story written in brick and steel.

The legends surrounding it have grown over the decades, passing from whispered tales to online forums, from hushed conversations to local folklore.

No matter how much time passes, the stories refuse to fade.

Visitors tell of strange encounters.

A woman in white glimpsed through the shattered glass of an upper window, the sound of footsteps echoing through empty halls, always just behind, never ahead.

The scent of something metallic, blood or rust, hung in the stagnant air.

Building 93, the hospital's towering relic is said to be the most haunted.

Some say the spirits of those who suffered there never left.

Others claim the building itself remembers.

Reports stretch beyond mere sightings.

Electronic devices falter near the ruins, flashlights flicker, cameras refuse to focus, recordings capture faint voices where there should be none.

The firehouse, the old doctor's cottages, and even the gutted remains of administrative offices have their own stories.

A former ward, once reserved for the violent and the forgotten, still carries the weight of its past.

Some who step inside describe a crushing sense of dread, as if unseen hands press against their chests as if the building itself wants them out.

Not all the ghosts of Kings Park Psychiatric Center are said to lurk within its crumbling walls.

At Shanahan's Bar & Grill, just down the road, regulars swap uneasy glances when the conversation drifts to the woman in the window.

She appears late at night, staring from the street, unmoving, her gaze locked on something, or someone, inside.

Then, in the space of a breath, she's gone.

Some say she's tied to the legend of Mary Hatchet, a specter whispered about in Long Island's darker folklore.

Others believe she's just another lost soul, tethered to the town by something stronger than time.

Whatever the truth, sightings like these have only deepened Kings Park's reputation as a place where the past refuses to settle.

The hospital may be abandoned, but it does not sleep.

Its walls crack, its roof sags, but its presence clings to the land like a stain.

Wander too close, and the air feels heavier, thick with something unseen.

Some places let go of their dead. Kings Park Psychiatric Center does not.

Big empty buildings often gather this kind of nonsense about them. When New York State decided to excess the Central Islip Psychiatric Hospital, I was the second person from New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) to go thru the place in anticipation of purchasing it as an additional campus. It was still functioning and the Hospital Director and I needed to avoid entering some of the in-use treatment rooms.

The Director took me thru the place and one stop was the Museum -- where each of the treatment modalities was displayed, from back in the late 1890s until the present. Some were downright frightening -- until my guide reminded me that, "When each of these treatments was used, they were the very best treatment that could be devised at the time, to help people with often terrible illnesses!"

Eventually, when the hospital closed and we (NYIT) began to look at cleaning out the buildings to prepare for the buildings' new role, I went thru the former Director's office and found 4 eight-foot shelves with file folders with complete patient records, back to the earliest days of the hospital. It turned out that New York State required that patient records less than 50 years old must be retained, but those older could be discarded. So the hospital closed, the people moved out, but the older records remained.

The records were complete detailed histories of each patient, from the time each entered -- sometimes as children (!) -- until they left, or often died and were buried in the on-site cemetery. What happened with each patient, what treatments they received, etc. were all recorded in detail, in each person's record folder.

I thought the records might be of real value -- for historical information, research, etc. -- but after searching every resource I could think of (libraries, other colleges, hospitals, etc.) I was unable to find anyone who would accept those files.

So the files were put into a dumpster and the reconstruction of the facility continued!

Your story adds needed realism. These weren't just ghost stories waiting to happen—they were places of care, complicated and imperfect. It's funny how time can turn functioning buildings into folklore.