A City of the Forgotten - The Rise of Pilgrim State Hospital

The old roads leading to Pilgrim State Hospital were never meant for traffic this heavy.

By the late 1920s, Long Island was changing - farm fields were giving way to housing developments, and the city's problems were spilling into the suburbs.

New York's asylums were bursting at the seams. Kings Park and Central Islip, once seen as solutions, had already exceeded their capacity. So, in 1929, the state made a decision: build bigger.

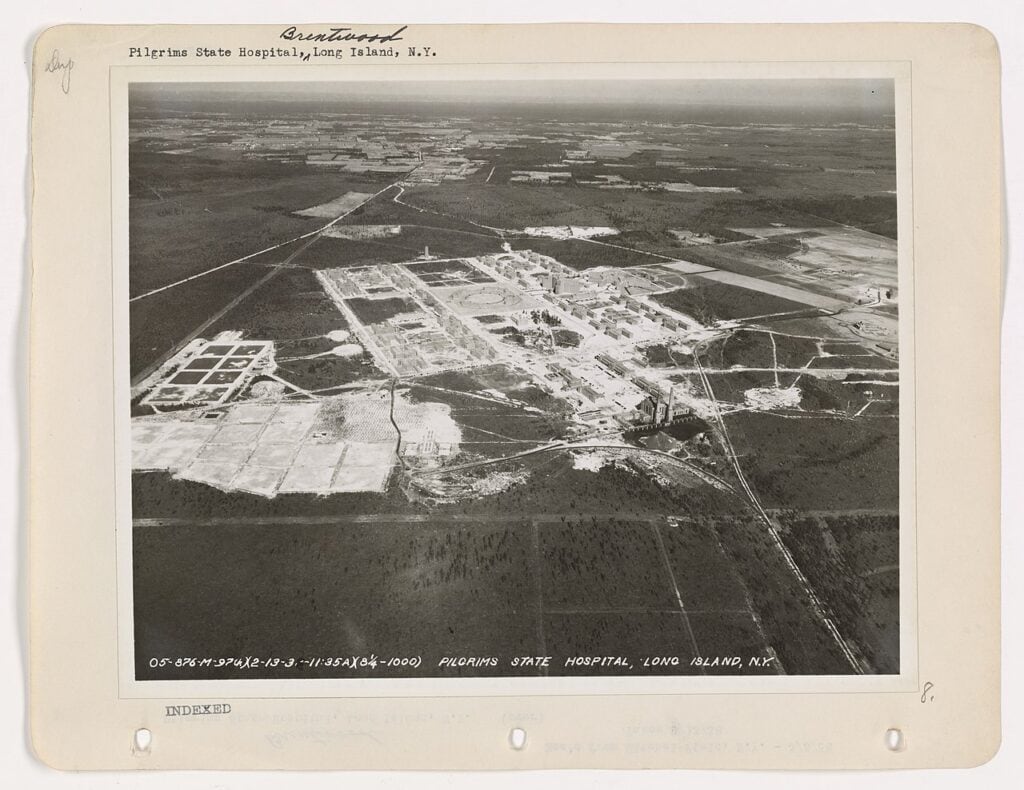

On October 1, 1931, Pilgrim State Hospital opened in Brentwood, Suffolk County. It wasn't a hospital in the way most people imagine - it was a town.

Spanning nearly 1,000 acres, it had its own police and fire departments, post office, power plant, and even a Long Island Rail Road station.

The layout followed a strict pattern: groups of four buildings formed "quads," with a central structure housing kitchens and dining halls.

Beneath it all, a network of tunnels kept utilities out of sight and staff moving between buildings without ever stepping outside.

By 1954, Pilgrim had reached its peak. With 13,875 patients, it was the largest psychiatric hospital in the world.

No other facility had housed so many before or since. The hospital expanded into neighboring towns - Huntington, Babylon, Smithtown, and Islip.

Two state highways ran through the property, giving it the feel of a city within a city.

As more patients arrived, the state needed even more space. As an extension, a new facility, Edgewood State Hospital, was built.

Pilgrim State Hospital wasn't just about treatment - it was a machine. Patients worked on farms, tending to livestock and growing crops.

The idea was simple: give them purpose and keep them occupied. But behind the fields and orderly brick buildings, the methods of care were evolving.

Electroconvulsive therapy, insulin shock, and lobotomies were on the rise.

The system was growing faster than anyone had expected. And soon, it would start to break.

Inside the Walls - The Business of Treatment

The doors locked with a hollow clang. Patients lined up in the hallway, waiting for their morning dose. Nurses moved fast - too many people, not enough staff.

At Pilgrim State Hospital, treatment was routine, efficiency mattered more than conversation, and no one had time to ask questions.

By the 1940s, the facility had expanded beyond what was originally planned. The state kept funding new wings, hiring more doctors, and testing new treatments.

Lobotomies were performed at a growing rate, especially after Dr. Walter Freeman popularized the transorbital method - quick, cheap, and devastating.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) became standard practice, with rows of patients strapped to tables, their bodies jerking under the current.

The belief was simple: the brain could be reset, like an old radio knocked back into place.

In the basement of one building, insulin shock therapy was administered daily. Patients were injected with insulin to induce seizures. Some recovered, some didn't.

The practice faded in the 1950s as psychiatric drugs entered the market, but for years, it was considered one of the best ways to treat schizophrenia.

Beyond the hospital walls, New York was growing. Long Island's economy boomed after World War II, with new housing developments, schools, and businesses.

But inside Pilgrim State Hospital, time moved differently. The wards remained full, and although the methods changed, the numbers didn't drop.

The hospital operated like a factory - patients came in, treatments were applied, and discharges were rare.

In 1945, the U.S. Army took control of part of the hospital. Buildings 81 through 83 and the nearby Edgewood State Hospital were renamed Mason General Hospital, a military psychiatric facility.

Battle-shocked soldiers arrived from Europe and the Pacific, their minds frayed from war.

Filmmaker John Huston documented their treatment in Let There Be Light, a film so controversial the government buried it for decades.

By the early 1950s, Pilgrim State Hospital had become the largest psychiatric hospital in the world.

But cracks were already forming. The next decade would bring changes that no one could stop.

The Rise and Fall - Breaking the System

By 1958, something had shifted. Pilgrim's director, Dr. Henry Brill, had seen the future of psychiatry, and it wasn't in padded rooms or locked wards.

Pharmaceutical companies were rolling out new drugs - thorazine, haldol, and stelazine - offering an alternative to long-term institutionalization. The days of mass confinement were numbered.

The cuts came slowly, almost unnoticed at first. Through the 1960s, state funding drained out of hospitals and into community programs.

The idea sounded good - move patients into supervised housing, offer outpatient care, and shrink the asylums.

But the reality was messier. Beds disappeared faster than services replaced them. Some patients made the transition, while others slipped through the cracks.

By the 1970s, Pilgrim State Hospital was shrinking, and some buildings sat empty. Edgewood State Hospital closed in 1971.

Kings Park and Central Islip Psychiatric Centers were still open, but their patient numbers were dropping.

Parts of Pilgrim were repurposed - a few buildings became a correctional facility for a short time, but local protests shut it down. Other structures were left to decay.

In 1974, Suffolk County Community College took over a portion of the old hospital grounds.

New halls replaced former treatment centers, though some original buildings remained, their past hidden behind fresh coats of paint.

By the 1980s, much of Pilgrim State Hospital was closed off, but the main hospital still operated.

The final blow came in 1996. The New York State Office of Mental Health shut down Kings Park and Central Islip, transferring the last patients to Pilgrim or into community programs.

It was the end of an era - the death of the state hospital system that had defined psychiatric care for nearly a century.

What remained of Pilgrim State Hospital operated at a fraction of its former size.

The old buildings stood like ghosts, waiting for whatever came next.

Pilgrim in Pop Culture - Crime, Tragedy, and Influence

On a cold December morning in 1979, the phone rang at Suffolk County Police headquarters.

By the time officers arrived, it was too late - Ewa Berwid lay dead in her Long Island home.

Her ex-husband, Adam Berwid, had been granted a day pass from Pilgrim State Hospital. He used it to find her.

Berwid had warned everyone. He sent letters, issued threats, and even stood before a judge and said he would kill her.

The system listened - but did nothing. In 1980, 60 Minutes aired Looking Out for Mrs. Berwid, unraveling the failures that handed a violent man a day pass and left his ex-wife dead.

Five years later, Hollywood turned the case into Murder: By Reason of Insanity, starring Candice Bergen.

Pilgrim State Hospital's Building 14 became a film set, and some of its staff landed small roles.

But the story was never about them - it was about a woman who never should have died.

Pilgrim's reach stretched beyond crime dramas. In 1956, Allen Ginsberg's mother, Naomi Livergant Ginsberg, died within its walls.

Schizophrenia had shaped much of her life - and his. Howl, his most famous work, carried echoes of her struggles, her confinement, and her slow disappearance inside the system.

The hospital loomed in the background, a real place turned into a metaphor.

Cropsey (2009) blurred the line between campfire story and real horror. It followed the case of Andre Rand, a convicted child kidnapper, tying him to Staten Island's decaying asylums.

Somewhere in that tangled history sat Pilgrim - Rand's mother had reportedly been a patient there, another name lost in the institution's long shadow.

Some stories weren't scripted. On an Easter Sunday, a one-armed patient named Barry Waszcyszak was beaten by an aide wielding a chair.

Bruised and bloodied, he became another name in Pilgrim's long record of abuse allegations.

The aide was arrested and charged with second-degree assault. But like most incidents behind Pilgrim's doors, the case faded from public view, leaving only another scar on the institution's past.

What Remains - The Aftermath of Decline

The demolition crews arrived in 2003. Brick by brick, the old medical buildings came down, leaving behind stretches of empty land and the shells of what once were treatment centers.

The wards that had housed thousands were gone, their histories reduced to foundation scars in the dirt.

By then, Pilgrim Psychiatric Center was operating on a fraction of its original scale.

The remaining facilities still handled patients, but the institution that once defined mental health care in New York was now a relic.

Some buildings stayed in use, while others were locked up, left to collect dust.

Even in their silence, they held echoes of what had happened there - hallways where nurses once rushed between rooms, treatment wings where doctors tested theories, and locked doors that had kept the outside world at bay.

Beyond the hospital grounds, the land was changing. A 52-acre section was converted into Brentwood State Park, now filled with athletic fields instead of psychiatric wards.

Another portion became the Suffolk County Community College Grant Campus.

Students walked across paths where patients once lined up for their daily medications, the past hidden beneath layers of asphalt and new construction.

Some attempts were made to preserve history. The Long Island Psychiatric Museum, housed in Building 45, collected artifacts from Pilgrim, Kings Park, and Central Islip.

Old medical instruments, photographs, and patient records filled the space - until 2020, when a flood wiped out much of the collection.

The building remains, but much of what was saved is still being restored.

New York State's Office of Mental Health Police patrols the old campus. Their job isn't just security - it's keeping people out.

Urban explorers still try to sneak onto the property, hoping to see what's left.

Some come for history. Others just want to step inside a place that once held the forgotten.

The Land That Time Won't Let Go - The Fight for Redevelopment

Developers have eyed Pilgrim's land for years. In 2002, real estate investor Gerald Wolkoff bought 462 acres of the former hospital grounds for $21 million.

His plan? A massive $4 billion project called Heartland Town Center.

The proposal included over 9,000 apartments, retail centers, office buildings, and entertainment spaces.

It was designed as a city within a city - echoing the scale Pilgrim State Hospital once had but with luxury housing and high-end businesses instead of psychiatric wards.

The project gained traction, but zoning approvals slowed it down. Environmental concerns, infrastructure challenges, and debates over traffic impact kept construction from breaking ground.

By 2017, Islip's town board approved the first phase, but as of 2025, much of the land still sits untouched.

In the meantime, other plans surfaced. One pitched a freight hub, repurposing an old Long Island Rail Road siding that once shuttled supplies and visitors to the hospital.

The idea met resistance quickly - locals didn't want truck traffic and warehouses swallowing what little open space remained.

While developers wait, the land remains in limbo. Some parts of Pilgrim's old grounds have already been reclaimed by nature - trees pushing through cracked pavement, vines wrapping around empty structures.

Other sections are fenced off, waiting for the next chapter in their long, unsettled history.

Recent Developments - Environmental Hazards and Mental Health Gaps

The air smelled sharp - chemical, unnatural. Workers in hazmat suits moved carefully across the grounds of Pilgrim Psychiatric Center, assessing the damage.

For years, the land had been in limbo, waiting for redevelopment. Instead, it received illegal dumping - barrels of hazardous waste buried beneath the soil.

In 2023, authorities uncovered a toxic secret - a Bay Shore man had been dumping hazardous waste on Pilgrim's grounds for years.

The case played out in court, exposing contamination buried in plain sight. The hospital, already a fractured mix of active wards and empty shells, now had another crisis - cleanup.

Locals had questions. If this went unnoticed for so long, what else was lurking beneath the soil?

Inside the hospital, another crisis was unfolding. Psychiatric beds vanished while the demand for care kept climbing.

Patients waited longer, and some turned away outright. The system was shrinking when it needed to grow.

A report from the New York State Comptroller's Office confirmed what patients and families had long suspected - that people in need of care were being turned away.

Some ended up in emergency rooms, others on the streets.

Brentwood officials argued over Pilgrim's future - redevelopment plans stalled, tangled in the hospital's past.

The hazardous waste scandal only slowed things further. Meanwhile, mental health advocates pushed back, insisting that slashing wards and gutting services had left more damage than it ever solved.

In early 2024, local leaders promised to address the psychiatric bed shortage.

However, solutions take time, and the land beneath Pilgrim State Hospital holds more than just history - it holds questions no one has fully answered yet.

I hope they get this place up and running! The future is NOW! This area needs a revamp quickly. I see housing, schools, entertainment, parks, and private citizen investors in my mind.

The state NEEDS to get this done!

The sheer size of the Pilgrim site means the potential is massive, but so are the logistics. Housing and parks could change the area entirely—if the planning follows through.