What's Left Behind the Wall

There's a stretch of riverfront just west of downtown Pittsburgh that once held 1,500 inmates behind thick limestone.

Most folks called it the Western Pen, though maps later labeled it State Correctional Institution - Pittsburgh. The site still stands, but time is picking at it. The state plans to knock it down by 2027.

For anyone who ever wondered where the idea of hard time met real brick and steel, the story starts here, before steel even defined the city.

Foundations of Incarceration - The Birth of Western Penitentiary

Western Penitentiary opened in 1826.

It was Pennsylvania's response to overcrowded conditions in the East and the beginning of formal incarceration west of the Atlantic Plain.

The original building sat two miles from the current site, near what's now the National Aviary.

William Strickland, a major architect of public buildings at the time, designed the prison.

The state built it as part of its early experiment with the Pennsylvania system, strict isolation for prisoners with the idea that solitude led to repentance.

That early prison drew outside attention. Charles Dickens visited the site between March 20 and March 22, 1842.

He documented the experience in his later writings, reflecting on the method of solitary confinement used at the facility.

His impressions weren't favorable. He described the practice as psychologically disturbing, even if it was well-intended by reformers of the day.

The Civil War brought in another kind of population.

On August 5, 1863, the prison began housing 118 Confederate soldiers captured during Morgan's Raid.

They remained there until March 18, 1864, before being transferred to a military fort in New Jersey.

Official records suggest conditions were considered relatively stable for the time, but at least eight of those prisoners died over that winter. One drowned trying to escape.

The original penitentiary was demolished in 1880, two years before the new facility opened farther west.

What once stood as a concrete extension of the Pennsylvania penal philosophy now exists only in records and a few photos buried in archives.

The site became part of Allegheny Commons Park, not far from today's tourist paths in the North Side.

Building the Fortress - The 1882 Rebuild and Physical Expansion

By 1882, Pennsylvania was ready to move Western Penitentiary to a new location.

The original site had aged poorly, and the corrections philosophy had started drifting away from strict isolation.

The new prison rose on 21 acres near the Ohio River, about five miles west of Pittsburgh's core.

Twelve of those acres sat behind the perimeter fence.

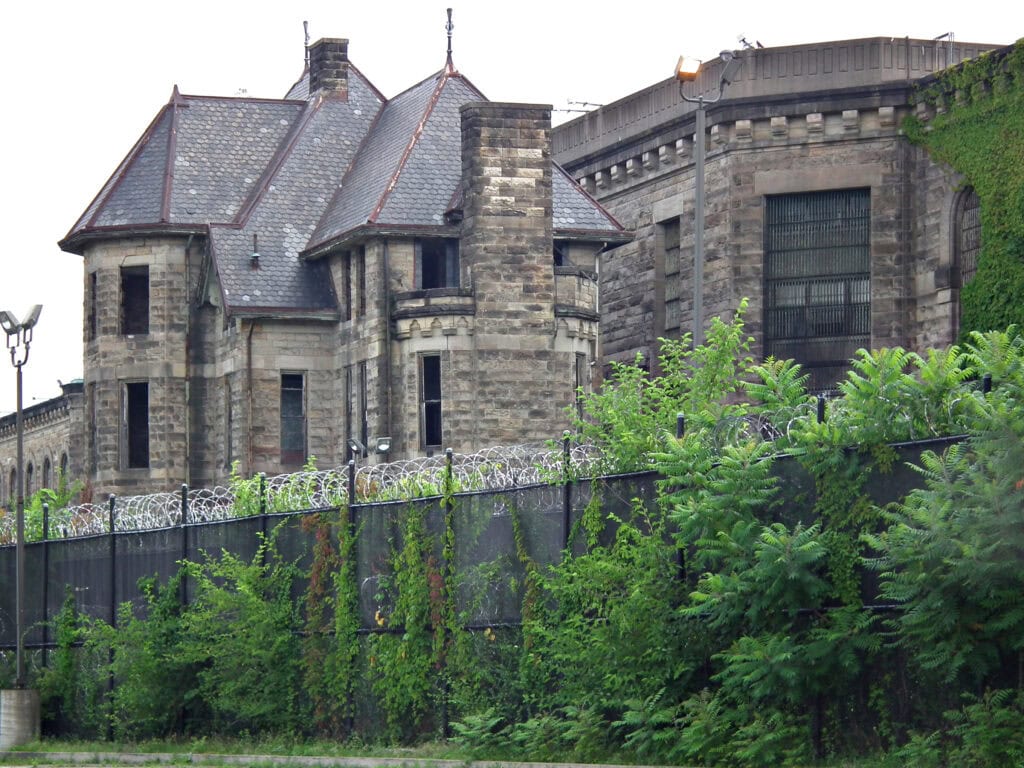

The state chose architect Edward M. Butz for the job, and his design leaned heavily on Romanesque touches: thick stone, narrow windows, heavy towers.

It looked more like a medieval fortress than a modern lockup.

Prison records from the early 20th century show a gradual expansion of the facility's footprint.

Beyond the main cell blocks, the campus grew to include medical units, a cafeteria, industrial workshops, administration offices, and a chapel.

Surveillance changed, too. By the 1930s, new guard towers and barbed-wire reinforcements were in place along the wall's edges.

The prison's classification didn't stay fixed.

Although it opened as a maximum-security site, housing some of the state's longest-serving inmates, its status shifted over time.

By the 1990s, the Department of Corrections had transitioned Western Penitentiary to a lower-security facility, focusing more on rehabilitation and substance abuse programming.

In the early 1980s, modernization efforts brought updated plumbing, upgraded wiring, and revised security protocols.

Surveillance cameras replaced human watchers in parts of the yard, and electronic locking mechanisms reduced the need for manual keys.

The state kept the old masonry, but beneath the stone, the place was adapting to new pressures.

Riot Cells and Escape Routes - Internal Tensions and High-Profile Cases

Western Penitentiary rarely drew headlines for good news.

Its reputation tilted toward escapes, failed breakouts, and inmates who attracted outside attention.

In the early 1980s, tension inside the facility boiled over during a riot.

Police responded with fire, literally. Reports show officers set parts of the building alight to regain control.

The flames were quickly extinguished, but the message was clear: containment over dialogue.

Among the most documented inmates was Alexander Berkman.

He entered the facility in 1892 after trying to shoot industrialist Henry Clay Frick.

Berkman's sentence lasted 14 years. He later wrote about those years in Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, published in 1912.

The book became a rare first-person account of life inside Western Penitentiary at the turn of the century.

George Feigley, the founder of a cult with criminal convictions tied to him, also passed through Western Penitentiary.

His name entered state reports again in 1983 after two of his followers drowned near the prison.

Investigators believed they were trying to reach him, possibly to plan a breakout.

By then, the Department of Corrections had already moved Feigley there to prevent a separate helicopter escape from SCI-Graterford.

Then came 1997. Six men disappeared in the middle of a shift change, slipping out with uniforms and forged passes.

The escape became known as "The Pittsburgh Six." Their story ran on multiple docudrama series in the 2000s, including Breakout on National Geographic and History's Greatest Escapes with Morgan Freeman on the History Channel.

Local coverage at the time detailed how faulty gates and poor oversight made the whole thing possible.

G-20 Logistics Hub - One Week Back in Operation

When Pittsburgh hosted the G-20 Summit in September 2009, the state used Western Penitentiary to process and hold detainees arrested during the protests.

The prison became a short-term holding site. Law enforcement needed a place to process people quickly.

Western Penitentiary had the space, the cells, and the security setup. It was available, and it worked.

On September 24 and 25, demonstrations swelled near Oakland and Downtown.

Police made arrests in clusters, on side streets, sidewalks, and intersections cleared with tear gas and LRADs.

More than 190 people were taken in. Buses dropped many of them at Western Penitentiary.

Most were held for less than 24 hours. Some walked out with citations. Others waited for arraignment.

Civil rights attorneys stepped in. The ACLU filed complaints about bail decisions and conditions inside.

Local news reported delays, crowding, and a lack of legal access.

There was no formal processing center elsewhere in the city, so the prison stood in.

The building was intact. Nothing broke down. No fires, no internal incident reports. Plumbing worked.

The lights stayed on. The site was functional, but only because it hadn't yet been gutted or sold.

Once the summit ended, it went dark again.

The cells were locked, the gates re-secured, and Western Penitentiary returned to standby, its brief return buried in press coverage and court filings.

The Shutdown Process - Wind-Down, Study, and Scheduled Demolition

The state closed Western Penitentiary in 2005. SCI-Fayette took its inmates.

Western sat quietly for two years. In 2007, it reopened, no ribbon-cutting, no overhaul.

The name changed to SCI-Pittsburgh. The population shifted to low- and medium-security.

Many were in recovery programs. By 2017, the prison closed for good. Governor Tom Wolf made it official on January 26.

The buildings stayed up. The Department of General Services held the title.

In 2022, the property was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

That didn't change the plan. The listing recognized the Civil War detainments, the architecture, and the age of the site.

It didn't require preservation.

In 2023, the state hired Michael Baker International for a feasibility report.

The results pointed in one direction.

The interior was compromised, with mold in the walls, asbestos in the insulation, and lead-based paint across multiple wings.

Gutting and restoring it would cost more than tearing it down.

The state decided to remove the entire facility.

Remediation is scheduled through 2027. The land, 21 acres near the Ohio River, will be listed for sale after demolition.

Private proposals came in. Some pitched haunted tours. One suggested a jail-themed hotel. None had long-term funding or operational guarantees.

Without that, the Department of General Services moved forward.

Western Penitentiary will be leveled. The sale comes next.

🍀

I worked 20 years at SCI Pittsburgh. Your report is about 80% accurate. There are a lot of old corrections officers around, you should have checked your facts with some of them.

You're absolutely right about checking with former staff. There's no substitute for firsthand experience, especially in a place like SCI Pittsburgh, where so much happened behind locked doors.